Search

Recent comments

- desecration....

49 min 10 sec ago - japan wins....

1 hour 57 min ago - nuances?....

2 hours 2 min ago - smaked by daddy....

2 hours 8 min ago - trust no-one....

4 hours 18 min ago - threesome....

4 hours 28 min ago - framing....

5 hours 28 min ago - epstein UK....

6 hours 24 min ago - toleration....

6 hours 45 min ago - poor judgement....

6 hours 55 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

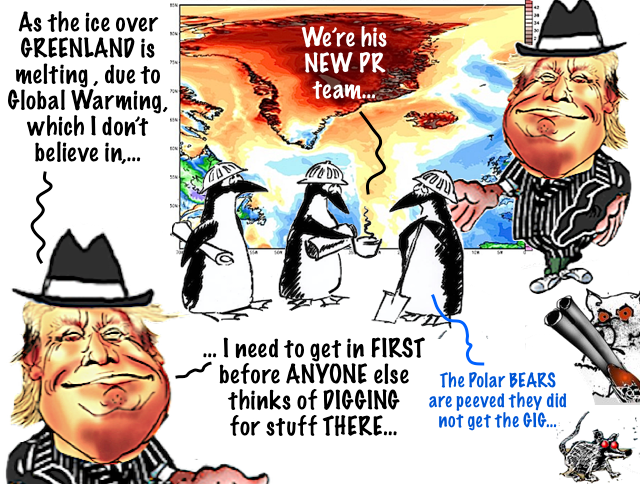

the race for whatever in greenlandia has started.....

Amid growing geopolitical turbulence and intensifying competition for strategic resources, the Arctic is becoming a key theater of global rivalry. Energy policy in the modern world is a central element of national and international strategy.

What exactly are Greenland’s riches that Trump wants so much?

Undeveloped oil and rare-earth reserves will require massive investment, but the island‘s political agency is priceless

By Igbal Guliyev

In recent weeks, Greenland has once again found itself at the center of international news. Donald Trump, having returned to the White House, has not simply returned to the old idea of ”purchasing” the island – he’s now talking about “full and indefinite access,” payments of a million dollars to each resident, and even annexation plans.

Let’s examine why this icy territory has become so hot.

Geologically, Greenland’s resources can be assessed as significant, but economically, they are still hard to access. Greenland is a resource-rich but underdeveloped Arctic island with proven reserves of gold and a range of metals, suspected but unrealized oil and gas potential, and serious environmental, infrastructural, and political constraints on their economic development. The conversation about Greenland is rooted in long-term shifts in the global economy and security. Following Trump’s statements and responses from local authorities, the discussion has shifted to practical matters: who exactly will gain access to these resources, and how will this change the balance in the Arctic?

In early 2026, Greenland firmly established itself as a central indicator of global geopolitical and geoeconomic transformations, where the interests of great powers, climate challenges, and the struggle for control of critical resources intersect in the face of accelerating melting of Arctic ice. According to US estimates (as recently as 20 years ago), up to 30 billion barrels of oil are hidden beneath glaciers and continental shelves, despite three decades of exploration by major companies such as Chevron, ENI, and Shell having yielded no commercial discoveries. A moratorium on new licenses was later imposed in 2021 due to climate concerns. The Jameson Land Basin contains projects with potential reserves of four billion barrels. The problem is the lack of infrastructure and the need for spill safeguards, estimated at billions of dollars.

Despite Greenland’s rich mineral resources, only nine active mines have opened since World War II. Only two are currently operating: the White Mountain anorthosite mine and the small, high-grade Nalunaq gold mine.

Rare earth metal mining is not currently underway. Poor transport and energy infrastructure hinders development. Large-scale rare earth metal mining in Greenland requires significant investment in creating suitable conditions.

The stakes for global powersChina has no Arctic territory, but is actively developing an economic presence through the Australian company Greenland Minerals, which plans to mine rare earths on the Kvanefjeld mineral deposit in the south of the island. China is willing to invest in Greenland’s infrastructure to support its mining projects and Arctic plans. However, so far, no major projects have been implemented. In 2018, a Chinese construction company participated in a tender for the construction and expansion of airports in Greenland’s capital Nuuk, as well as the towns of Ilulissat and Qaqortoq. The project was estimated to cost nearly $550 million. This angered the US and Denmark. US Secretary of Defense James Mattis called on the Danish government to intervene to prevent China from gaining a foothold in the region. Denmark withdrew from the tender and financed the airport upgrades itself to prevent China from participating. Although Denmark intervened due to security concerns, Greenlanders’ desire for economic independence may yet push them to accept foreign investment from China.

Russia, which controls the Northern Sea Route, views the strengthening of the US position in Greenland as a threat to its Arctic interests, especially in the context of cooperation with China on Arctic Ocean development.

Greenland is strategically important because it contains all kinds of rare earth metals, including neodymium and dysprosium, which are needed for powerful magnets in electric vehicles and wind turbines. It also contains terbium, which makes magnets more heat-resistant, and praseodymium, which enhances their magnetic properties.

Competition for key minerals is growing as countries seek to reduce their dependence on suppliers. This is driving interest in deposits in remote regions where mining was previously unprofitable due to challenging conditions. The Arctic is one such region where climate change and geopolitics are impacting Greenland’s rare earth resources and its strategic location.

The mining industry typically focuses on accessible deposits with good technological indicators. However, supply issues have forced a reconsideration of projects that offer diversification benefits, even if they are more expensive. Governments and companies are now evaluating mining projects based not only on economic benefits but also on strategic security.

Greenland found itself in the spotlight due to the Cold War over the Arctic. Denmark gained sovereignty over the island in 1933, granted autonomy in 1979, and transferred control of its resources to local authorities in 2009. Foreign policy and defense, however, remained under Copenhagen’s control.

Trump has stated that the US needs Greenland for national security reasons. His aides have suggested that the US could seize Danish territory to protect its interests. This underscores the Trump administration’s view of resource security as a matter of national importance. Greenland contains iron ore, graphite, tungsten, palladium, vanadium, zinc, gold, uranium, copper, and oil. But rare earth elements have attracted the most attention. The US is concerned about the supply of rare earth elements for defense and commercial industries. In 2024, the US escalated the situation. Donald Trump declared “the need for American control of Greenland as a key element of US defense” and even threatened a military takeover, sparking concern in Europe. EU countries such as France, Germany, the UK, and Italy emphasized that Greenland belongs to its residents and began discussing a stronger military presence in the Arctic. In 2025, China imposed export controls on certain rare earth elements, leading to supply disruptions and production halts at Western automakers. Trump took steps to address these issues, such as a partnership with the American company MP Materials and agreements with Saudi Arabia, Japan, and Australia to develop deposits outside of China.

The EU remained silent for a long time, but in 2023, it signed a cooperation agreement with Greenland and allocated funds for the Malmbjerg molybdenum mine. As the former Danish foreign minister noted, Europe risks missing its opportunity and ceding control of strategic resources to the US and China.

Greenland’s wealth lies not only in gold, oil, and rare earth elements, but also in its Arctic location and political agency. Greenlanders don’t sell out their identity, even for astronomical sums – they measure their wealth not in barrels of oil, but in sovereignty, environmental sustainability, and connection to European values. It’s important to remember: the question isn’t whether Greenland is rich. Arctic wealth is difficult to access due to the short drilling season and the lack of roads, ports, and pipelines. The key is who and how quickly it will develop its resources in the face of climate change and geopolitical competition.

Not only the island’s future depends on this, but also the balance of power in the Arctic, which is no longer a backwater but a battleground for influence. Greenland is showing the world that in the 21st century, the greatest wealth lies not in ice reserves, but in the ability to independently determine one’s own destiny.

NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte has stated that the agreement he reached with US President Donald Trump on Greenland will require alliance allies to strengthen Arctic security. “I have no doubt that we can do this quite quickly. Of course, I hope for 2026, hopefully even early 2026,” he said in an interview with Reuters.

The framework agreement in question was discussed by Rutte with Trump on January 21 on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum in Davos. According to media reports, it is envisaged that Denmark will retain sovereignty over Greenland, but the US will be able to build military bases on the island with ownership rights. The Danish authorities maintain that the NATO secretary-general did not have the authority to conduct such negotiations.

The process of changing Greenland’s status in the mid-20th century became one of the most illustrative examples of how a small state managed to exploit international legal mechanisms and geopolitical circumstances to maintain control over a territory formally considered a colony.

Greenland in 2026 confirms a trend: small resource territories are becoming arenas for “resource neocolonialism,” where the US, through Trump, imposes hybrid control, the EU lags behind, and Russia and China respond symmetrically. The sovereignty of small actors is vulnerable to climate and minerals, making the Arctic a new pole of multipolarity. Greenland’s energy potential – from hydrocarbons to rare earth elements – remains more of a strategic asset than an immediate economic driver due to technological, environmental, and political barriers requiring multibillion-dollar investments and international cooperation.

With Arctic ice melting and resource diplomacy escalating, the island could become the catalyst for a new Arctic Cold War, with priority shifting from oil to minerals for decarbonization. Prospects depend on the balance between Greenland’s independence, Denmark’s alliance commitments, and global sustainable development norms. A realistic scenario is a partnership with the West for phased extraction over the medium term, with the risk of escalation if Trump’s pressure becomes coercion.

Ultimately, Greenland illustrates the paradox of modern geoeconomics: resources hidden beneath the ice threaten to melt not only the climate but also established alliances, requiring global policymakers to take strategic foresight for the sake of collective security.

https://www.rt.com/news/632221-greenland-riches-trump-wants/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 10 Feb 2026 - 10:56am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

smaked by daddy....

It is one year since US Vice-President JD Vance delivered a bombshell speech at the Munich Security Conference, castigating Europe for its policies on migration and free speech, and claiming the greatest threat the continent faces comes from within.

The audience were visibly stunned. Since then, the Trump White House has tipped the world order upside down.

Allies and foes alike have been slapped with punitive tariffs, there was the extraordinarily brazen raid on Venezuela, Washington's uneven pursuit of peace in Ukraine on terms favourable to Moscow and a bizarre demand that Canada should become the "51st state" of the US.

This year, the conference - which begins later this week - once again looks set to be decisive. US Secretary of State and National Security Adviser Marco Rubio leads the US delegation, while more than 50 other world leaders have been invited. It comes as the security of Europe looks increasingly precarious.

The latest US National Security Strategy (NSS), published late last year, called on Europe to "stand on its own feet" and take "primary responsibility for its own defence," adding to fears that the US is increasingly unwilling to underpin Europe's defence.

But it is the crisis over Greenland that has really tugged at the fabric of the entire transatlantic alliance between the US and Europe. Donald Trump has said on numerous occasions that he "needs to own" Greenland for the sake of US and global security, and for a while he did not rule out the use of force.

Greenland is a self-governing territory belonging to the Kingdom of Denmark, so it was hardly surprising when Denmark's prime minister said that a hostile US military takeover would spell the end of the Nato alliance that has underpinned Europe's security for the past 77 years.

The Greenland crisis has been averted for now – the White House has been distracted by other priorities – but it leaves an uncomfortable question hanging over the Munich Security Conference: Are Europe-US security ties damaged beyond repair?

They have changed, there's no question about that, but they have not disintegrated.

Sir Alex Younger, who was chief of the UK's Secret Intelligence Service, MI6, from 2014-2020, tells the BBC that while the transatlantic alliance is not going to go back to the way it was, it isn't broken.

"We still benefit enormously from our security and military and intelligence relationship with America," he says. He also believes, as many do, that Trump was right to make Europe shoulder more of the burden for its own defence.

"You've got a continent of 500 million [Europe], asking a continent of 300 million [US] to deal with a continent of 140 million [Russia]. It's the wrong way around. So I believe that Europe should take more responsibility for its own defence," Sir Alex said.

This imbalance, whereby the US taxpayer has been effectively subsidising Europe's defence needs for decades, has underpinned much of the Trump White House's resentment of Europe.

But the splits in the transatlantic alliance go well beyond troop numbers and irritation at those Nato countries, such as Spain, that have been failing to meet even the minimum 2% of GDP on defence (Russia currently spends more than 7% on defence while Britain is just under 2.5%).

On trade, migration and free speech Team Trump have sharp differences with Europe. Meanwhile, democratically elected European governments have been alarmed by Trump's relationship with Vladimir Putin and his propensity for blaming Ukraine for getting invaded by Russia.

The Munich Security Conference organisers have published a report ahead of the event in which Tobias Bunde, the director of research & policy, says there has now been a fundamental break with US post-WW2 strategy.

This strategy, he argues, broadly rested on three pillars: a belief in the benefit of multilateral institutions, economic integration and a belief that democracy and human rights are not just values, but strategic assets.

"Under the Trump administration," says Bunde, "all three of these pillars have been weakened or openly questioned".

'A shocking wake-up call for Europe'Much of the Trump White House's thinking can be found in the US National Security Strategy. The Washington-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) describes the document as "a real, painful, shocking wake-up call for Europe", and "a moment of cavernous divergence between Europe's view of itself and Trump's vision for Europe".

The strategy states as a priority a new policy of supporting groups hostile to those very European governments that are supposed to be Washington's allies. It promotes "cultivating resistance to Europe's current trajectory within European nations", and says Europe's migration policies risk "civilizational erasure".

However, the document maintains that "Europe remains strategically and culturally vital to the United States".

"The majority of Europe's reaction to this NSS", says the CSIS, "is likely to be the same aghast shock as met Vice President JD Vance's Munich speech" in February 2025.

"We are currently seeing the rise of political actors who do not promise reform or repair," says Sophie Eisentraut of the Munich Security Conference, "but who are very explicit about wanting to tear down existing institutions, and we call them the demolition men".

The Narva testBut the ultimate question in all of this is "does Article 5 still work?".

Article 5 is the part of Nato's charter that stipulates that an attack on one country shall be deemed an attack on all. From 1949 until a year ago it was taken as read that should the Soviet Union, or more latterly Russia, invade a Nato state such as Lithuania then the full force of the alliance, backed by US military might, would come to its aid.

Although Nato officials have insisted that Article 5 is still very much alive and well, Trump's unpredictability coupled with the disdain his administration has for Europe inevitably calls it into question.

This is what I call "the Narva Test". Narva is a majority Russian-speaking town in Estonia that sits on the River Narva, right on the border with Russia. If, hypothetically, Russia were to make a grab for it under the pretext, say, of "coming to the help of its fellow Russians", would this US administration ride to the rescue of Estonia?

The same question can equally be applied to a future, and still hypothetical, Russian move on the Suwalki Gap which separates Belarus from the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad on the Baltic. Or, for that matter, the Norwegian-administered Arctic archipelago of Svalbard where Russia already has a colony at Barentsburg.

Given President Trump's recent territorial ambitions to seize Greenland from fellow Nato member Denmark, no one can predict for certain how President Trump would react. And that, in a time when Russia is waging a full-scale war against a European country in Ukraine, can lead to dangerous miscalculations.

This week's Munich Security Conference should provide some answers on where the transatlantic alliance is heading. They just may not necessarily be what Europe wants to hear.

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cgrzjv1kykxo

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.