Search

Recent comments

- equipment.....

30 min 6 sec ago - reckless....

59 min 35 sec ago - peaceful....

1 hour 2 min ago - worthless $....

1 hour 19 min ago - marx and the weather....

1 hour 23 min ago - no list....

15 hours 4 min ago - fire fire....

16 hours 32 min ago - kincora....

18 hours 9 min ago - war crimes....

20 hours 59 min ago - supplies....

23 hours 10 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

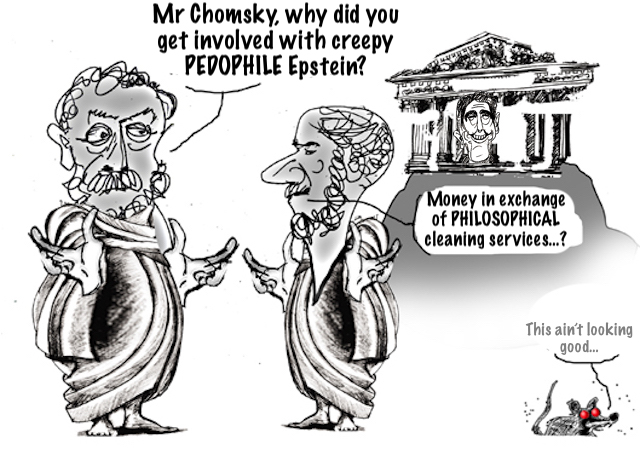

the philosopher and the sex trafficker were in contact long after epstein was convicted....

The prominent linguist and philosopher Noam Chomsky called it a “most valuable experience” to have maintained “regular contact” with Jeffrey Epstein, who by then had long been convicted of soliciting prostitution from a minor, according to emails released earlier in November by US lawmakers.

Chomsky had deeper ties with Epstein than previously known, documents reveal

This article is more than 2 months old

The philosopher and the sex trafficker were in contact long after Epstein was convicted of soliciting prostitution from a minor, documents reveal

BY Ramon Antonio Vargas

Such comments from Chomsky, or attributed to him, suggest his association with Epstein – who officials concluded killed himself in jail in 2019 while awaiting trial on federal sex-trafficking charges – went deeper than the occasional political and academic discussions the former had previously claimed to have with the latter.

Chomsky, 96, had also reportedly acknowledged receiving about $270,000 from an account linked to Epstein while sorting the disbursement of common funds relating to the first of his two marriages, though the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) professor has insisted not “one penny” came directly from the infamous financier.

The emails disclosed on 12 November by the Republican members of the US House oversight committee generally detailed the correspondence Epstein had with political, academic and business luminaries, including the Bill Clinton White House’s treasury secretary Larry Summers and Steve Bannon, the longtime ally of Donald Trump. Further, they reveal Epstein and Chomsky were close enough to discuss musical interests and even potential vacations.

Perhaps the most telling of the Chomsky-related documents in question was a letter of support for Epstein attributed to Chomsky with the salutation “to whom it may concern”. It is not dated, but it contains a typed signature with Chomsky’s name and citing his position as a University of Arizona laureate professor, a role he began in 2017, as first reported by the Massachusetts news outlet WBUR.

Epstein pleaded guilty in 2008 in Florida to state charges of solicitation of prostitution and solicitation of prostitution with a minor. He served 13 months of an 18-month sentence and was released in July 2009.

“I met Jeffrey Epstein half a dozen years ago,” read the letter of support from Chomsky that was reviewed by the Guardian after its Republican House oversight committee release. “We have been in regular contact since, with many long and often in-depth discussions about a very wide range of topics, including our own specialties and professional work, but a host of others where we have shared interests. It has been a most valuable experience for me.”

It is unclear whether Chomsky sent the letter to anyone. Nonetheless, it exalts Epstein for teaching Chomsky “about the intricacies of the global financial system” in a way “the business press and professional journals” had not been able to do. It boasted about how well connected Epstein was.

“Once, when we were discussing the Oslo agreements, Jeffrey picked up the phone and called the Norwegian diplomat who supervised them, leading to a lively interchange,” the letter read. The letter recounted how Epstein had arranged for Chomsky – a political activist, too – to meet with someone he had “studied carefully and written about”: the former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak.

Epstein had – “with limited success” – aided efforts from Chomsky’s second wife, Valeria, to introduce him “to the world of jazz and its wonders”, the letter continued.

It concluded, “The impact of Jeffrey’s limitless curiosity, extensive knowledge, penetrating insights and thoughtful appraisals is only heightened by his easy informality, without a trace of pretentiousness. He quickly became a highly valued friend and regular source of intellectual exchange and stimulation.”

Another notable communication involving Chomsky and Epstein is a 2015 email in which the latter offers the former use of his residences in New York and New Mexico.

The emails don’t indicate whether Chomsky took advantage of the offer, whose particulars surfaced as certain officials are striving to investigateallegations of crimes by Epstein at a ranch compound he owned outside Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Interest in the Epstein case has surged in recent months after Trump – a former friend of his – pledged to release a full list of the late financier’s clients while successfully running for a second presidency in 2024. However, after he took office in January, Trump’s justice department declared no such list existed and said that it would not be releasing any additional files related to Epstein’s prosecution, igniting a bipartisan furor that the president sought to dismiss as a Democratic “hoax”.

Yet the pressure was enough that Trump on Wednesday signed a legislative bill directing his justice department to release more of what has come to be collectively known as the Epstein files.

Chomsky is not the only renowned Massachusetts academic to be ensnared in the Epstein scandal. On Wednesday, Larry Summers relinquished a teaching role at Harvard University – where he was once president – after his email correspondence with Epstein revived questions about their relationship.

A statement that MIT provided to WBUR and the Guardian declined to comment on Chomsky but said the university in 2020 had reviewed its contacts with Epstein. “Following that review, MIT took a number of steps, including enhancements to our gift acceptance processes and donating to four nonprofits supporting survivors of sexual abuse,” the statement said.

The University of Arizona did not immediately reply to a request for comment on Chomsky. Neither did Chomsky. Nor did Valeria Wasserman Chomsky, who is a spokesperson for her husband – and in January 2017 sent an email to Epstein apologizing for not wishing him a happy birthday a couple of days earlier.

“Hope you had a good celebration!” she wrote to Epstein, according to the emails released by House oversight committee Republicans. “Noam and I hope to see you again soon and have a toast for your birthday.”

Chomsky hasn’t spoken publicly since he was reported in 2024 to be convalescing in Brazil after a stroke.

Anna Betts contributed reporting

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/nov/22/noam-chomsky-jeffrey-epstein-ties-emails

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 11 Feb 2026 - 5:55am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

marx and the weather....

I am not sure just what Marx had in mind when he wrote that "philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it." Did he mean that philosophy could change the world, or that philosophers should turn to the higher priority of changing the world? If the former, then he presumably meant philosophy in a broad sense of the term, including analysis of the social order and ideas about why it should be changed, and how. In that broad sense, philosophy can play a role, indeed an essential role, in changing the world.

Noam Chomsky

===============

The Point is to Change the World

By Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò

“The philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways,” he [Marx] famously said. “The point, however, is to change it.”

Karl Marx penned these words as a set of notes for a later work with co-author Friedrich Engels. Marx’s “Theses on Feuerbach” may have focused on the work of Ludwig Feuerbach, but it reflected a broader dissatisfaction with intellectual trends common to the other Young Hegelians of their day. The meat of Marx’s notes on this work are the second, third, and eighth theses, in which he reveals a thoroughly practical perspective on social life and thought on which the role of thought, and thus of philosophy, is to inform and transform activity. These theses, and the perspective they abbreviate, are why the above quote (the 11th and final thesis) serves as a mic drop.

Over a century later and an ocean away: “Old foundations are crumbling, and new ones are not yet being imagined.” To me, these words spoken by Afro-Guyanaese activist and intellectual Andaiye in a speech called “The Contemporary Caribbean Struggle”, sound a similar warning as Marx’s. I would guess that I am not alone in thinking so: Alissa Trotz named the collection of Andaiye’s essays in which I discovered this quote “The Point is to Change the World”, and Marx’s 11th thesis on Feuerbach serves as the book’s epigraph. But while Marx’s comment encapsulates the age-old struggle over the place of philosophy in any age, is Andaiye’s intellectual contribution that provokes us to ask its relevance in this one.

Andaiye’s ThoughtAndaiye was born on September 11th, 1941 in Georgetown, the capital of what was then British Guiana. She came of age while her country was marked with conflict: with the approval of President John F. Kennedy, the CIA conspired to rig the soon to be independent country’s elections, ousting the outspokenly Communist Indo-Guyanese Cheddi Jagan in favor of the perceived moderate Forbes Burnham. In a forward to “The Point is to Change the World”, Guyanese historian Clem Seecharan characterizes the Burnham administration as a dictatorship. He remained in power for sixteen years.

While her country descended into racial violence between what Seecharan described as a “virtual racial war between Africans and Indians”, a young Andaiye was hard at work studying and deepening her radical politics. She studied at the University of West Indies with fellow student and eventual comrade Walter Rodney, and later lectured in a program for “disadvantaged students” in the United States. She returned home with a staunch feminist and Marxist politics rooted in solidarity: among her many organizational affiliations are the Red Thread Women’s Organization in Guyana and the Working People’s Alliance. By 2009, when she was invited to give the speech at her alma mater, she was a seasoned, veteran activist, deeply attuned to the stakes of political analysis.

When Andaiye said that “old foundations are crumbling, and new ones are not yet being imagined”, she was not talking about the structure of philosophical analysis, or of patterns of political discourse. She was talking about the weather.

Andaiye went on to explain: “old assumptions about weather patterns and how these shape major economic occupations are no longer valid.” Climate crises in the Caribbean were mounting. Climate change might seem like a drop in the bucket in larger countries with advanced economies, but for the small island states of the Caribbean, it was an existential crisis. In 2005, her home country lost the equivalent of 60% of its GDP in a single flood that covered a mere 25 miles of its over 200-mile coastline.

Such ecological crises exacerbated longstanding forms of injustice and new developments in the world economy. After the flooding in Guyana, women caregivers and subsistence farmers shouldered massively increased burdens. But NAFTA likewise contributed to gender injustices: women were shuffled out of sectors like manufacturing at rates more than double the rates of male job loss – increasing their representation in the precarious informal sector, already disproportionately inhabited by women. Massive majorities of farming populations in Dominica were shunted out of the relatively secure formal sector and into the informal sector. Race violence increased in Guyana, police violence spiked in Jamaica, and domestic and sexual violence surged throughout the region.

Towards a Practical ImaginationConfronted by these crises, Andaiye said, such countries turned where they had to: to the IMF, despite the fact that little had changed since the “structural adjustment policies” of the 70s (which Andaiye describes as having a destructive impact on the region). In this context, I see Andaiye as calling for imagination: to overcome the lack of new solutions that forced the region back to familiar non-solutions.

Not all kinds of imagination are up to the challenge of confronting crumbling structures. One kind of imagination is artistic: the kind that science fiction writers and poets employ. We use our imagination creatively, often as part of the construction of an aesthetic product. This allows us to be comparatively unfettered by convention – or considerations of practical efficacy. There is an important role for this kind of imagination: it breaks us out of self-imposed constraints on what kinds of worlds are possible, and as such is indispensable in the fight for justice, in the final analysis. And there is plenty of this kind of thinking in the academy, particularly in the humanities, where we build fancy descriptions of justice and injustice alike, judging our successes and failures on largely aesthetic terms.

The question is one of balance: the more of our resources, time, and energy go to ignoring, wishing away, or bracketing our problems, the less goes to tackling them. We need the imagination to set targets, but we also need the imagination to find out how to reach them.

Thus, this is the wrong sense of imagination to do what Andaiye calls us to do. To build things, we need an architectural imagination aimed at building a political product. This kind of imagination plays an ineliminably practical role. The blueprints are just another step in the constructive process of building a house, and building its rooms: that is, the social structures where moral principles are given practical and concrete expression: the places where fights for justice are won and lost.

There is nothing inherently good about this perspective: the colonizer, too, is an imaginer and a planner, one who sees possibilities that diverge from what is happening now – ways to reorganize society around their own aggrandizement. Our evaluation of constructive projects has to be keyed to what is imagined, who is imagining, and what relations of accountability exist in and between the rooms that we build.

Philosophy and wider history are full of examples about how we can get going, but get going we must: now, more than ever, the retreat into the ivory tower and its very local problems is a massive failure: a failure of responsibility, a failure of care, and also a failure of imagination. There are other ways to be here, other ways of pursuing philosophical questions, other questions to pursue.

Climate crisis asks us a number of questions: how will we secure ourselves and each other in an increasingly precarious world, and what are the implications for justice of different approaches? How will knowledge networks respond to our changing political environment –the actual ones that we have, not (just) the idealized ones we use to answer questions we find fascinating? What political structures relate universities and researchers to the communities within and around them, and how should they operate?

Philosophers could do more – and could do the many helpful things they are doing much differently. First and foremost, we could follow our colleagues at Rutgers’ lead and organize ourselves in solidarity with all of the colleagues who make our campuses work: faculty and graduate workers, administrative staff, health care professionals, dining and student services, and building maintenance and operations, and the broader community our campuses are located in. Senior colleagues could develop serious research programs supporting the incredible complexities of climate crisis and actions, and support junior colleagues doing the like by explicitly building such social contributions into how their work is evaluated. Philosophers who work on psychology and moral emotions likely have much to contribute to discussions of climate governance and cross-institutional collaboration. Philosophers working with or adjacent to natural and social sciences could add to systems dynamic modelling in the climate world, which practitioners claim demands a large scale, multinational collaboration with the “urgency of the space race”. Regardless of what we study, we can all contribute an environment in which we encourage each other to ask how we can contribute constructively to this work, and value such contributions.

The number of climate questions, their scale, and their complexity are daunting. But in times like these, it is always helpful that we are not starting from scratch – we would simply be making an institutional effort to join colleagues who have been doing this work for decades. Philosophy and wider history are full of examples about how we can get going in contributing to society’s practical use of the particular questions we ask: from the network of collaboration established by the dedicated organizers of Philosophers for Sustainability (who put together this very blog section!); to the applied (and translational) sections of our own field, to the storied history of intellectual contributions to movements that Andaiye and her comrades exemplify.

Now, more than ever, imagining and building new foundations should be more than an acceptable section of philosophy: it should be the point.

https://blog.apaonline.org/2021/04/29/the-point-is-to-change-the-world/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.