Search

Recent comments

- success....

2 hours 39 min ago - seriously....

5 hours 23 min ago - monsters.....

5 hours 30 min ago - people for the people....

6 hours 7 min ago - abusing kids.....

7 hours 40 min ago - brainwashed tim....

12 hours 6 sec ago - embezzlers.....

12 hours 6 min ago - epstein connect....

12 hours 17 min ago - 腐敗....

12 hours 36 min ago - multicultural....

12 hours 43 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

swiss kids hunched over their black boxes....

“But everyone else has one!”

This refers to a child’s desire – often expressed very urgently to their parents – to finally get their own smartphone. It is not easy to stand firm in such situations. “I don’t want my child to be an outsider” is a frequently heard argument – and sometimes also an excuse to avoid what may to become a difficult discussion. But who hasn’t seen the images of children and teenagers sitting side by side, hunched over their black boxes?

by Eliane Perret

Driven by the fear of missing out? FOMO (fear of missing out), as it is known in technical jargon! A feeling that is deliberately evoked by the structure of social media.1 But the question remains: how do we protect our children and young people from slipping into a digital world associated with psychologically harmful content, psychiatric symptoms and addictive behaviour? Parents are therefore called upon to tackle the task and protect their children and young people from the pitfalls and dangers of digital media.2 However, it would be easy to join forces, as many parents want to keep their children and young people away from undesirable content on the internet and (mostly) anti-social media, but feel that they are alone in this.

Goal 14+

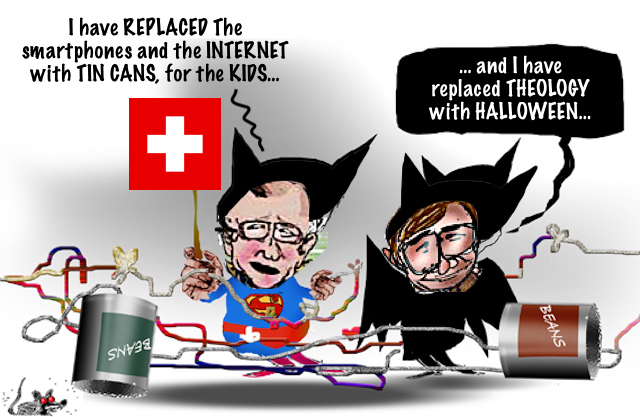

Some families from the municipality Sorengo in our southern canton Ticino are leading the way. They have joined forces in the “Obiettivo 14+” association.3 “Obiettivo 14+” started with a few courageous fathers and mothers. Today, the association has over 30 members from Lugano area – and more than fifty children are benefiting from it. No, no, these are by no means technophobic parents who want their children to still communicate with a tin can telephone, but rather they want to instil in their offspring a sense of JOMO (joy of missing out), namely the joy of not having to be part of it.

The name of their association means Goal 14+ in English. Membership is linked to a “Patto digitale”, a digital pact in which parents undertake not to provide their child with any personal digital devices connected to the internet until they reach the age of 14. This includes smartphones, tablets, smartwatches, game consoles, PCs (and all other devices that can connect to the internet). Personal means that the device was purchased for the child or is freely available to them – and that should not be the case. To enable telephone communication between parents and children, a newly produced “dumbphone” in the style of an old Nokia device is recommended, the use of which is limited to phone calls and sending text messages. A personal account on (un)social media is only permitted from the age of 16 on.

A careful introduction to the digital world

The “Patto digitale” can be found on the association’s website.4 Parents can use it – with slight variations, but essentially unchanged – for their family’s needs. It provides them with carefully thought-out and helpful guidelines on how to organise their family life in today’s technology-obsessed world. Parents are encouraged to participate in their children’s digital world. Parents’ devices or a shared PC or laptop are available in commonly accessible places such as the living room and kitchen. The rules, which are transparent to everyone, include fixed times and a precisely defined limited period of use. This gives children an insight into the advantages of the internet when searching for information, while at the same time teaching them to use devices consciously and responsibly. To prevent access to inappropriate content, special filters or blocks may need to be installed. The obligation to participate in the training offered as part of the membership makes it easier for parents to stick to their guns and stay on task.

Why no urgency?

It is easy to see that such regulated use of digital devices places demands on parents in many ways. Not only do they have to withstand what may be intense pressure from their children, but they also have to familiarise themselves with the technical aspects of responsible internet use. Not all parents are able to do this. This makes it all the more important for the federal government to introduce legal regulations and protective measures, as other countries have already done. It is astonishing that the Federal Council sees no real need for action in response to the postulates of National Councillor Maya Graf, Councillor of States Céline Vara and the motion of National Councillor Regina Durrer-Knobel.5 This raises the question: Why is the urgency of protecting our younger generation and the duty to support parents not recognised? Who has an interest in a disoriented and internally neglected youth?

Perhaps a tin can telephone after all?

In the meantime, parents have to help themselves, like those in Sorengo or those who have joined the Smartphone-Free Childhood association6. They can find many answers to pressing questions on the relevant websites. Here is one advantage of the internet: The answers on the Obiettivo 14+ website, which are written in Italian, can be translated into the desired language with a click using translation programmes. This makes it easier for parents to enjoy themselves with their children on the football pitch, build huts in the woods or have fun playing board games together in a warm living room in winter – a trip to the analogue world, where even a tin can telephone has its place. •

https://www.zeit-fragen.ch/en/archives/2025/nr-22-14-oktober-2025/aber-alle-haben-eines

===================

“Süsses oder Saures!” “Des bonbons ou un sort!” Thirty years ago, most Swiss wouldn’t have had a clue what was going on if they had opened their front door to find a couple of eight-year-olds, high on sugar and dressed as witches or skeletons, shrieking “trick or treat!”.

Since the mid-1990s, Halloween has embedded itself, albeit weakly, in Swiss cultural life. “Like Oktoberfests, which now also intoxicate town and country in Switzerland,” wrote the St. Galler TagblattExternal link, referring to German beer festivals.

“Cultural pessimists see domestic customs threatened,” it continued. “And evangelical Christians in particular reject Halloween because it’s about occultism and Satanism – regardless of the fact that the event has long since ceased to have any serious religious traits and is largely commercialised. Folklorists rather than theologians are responsible for Halloween, and marketing experts and event organisers for its spread in our country.”

The tradition crept into French-speaking Switzerland from France, and then into German-speaking Switzerland, according to folklorist Konrad Kuhn, who confirmed that Halloween wasn’t an issue in Switzerland before the mid-1990s.

It took a few years for the larger retailers and the media to get interested, but what really gave Halloween a boost in Switzerland was farmers’ discovery, at the same time, of the pumpkin as a new source of income, Kuhn wrote in Kürbis, Kommerz und KultExternal link: Halloween und Kürbisfest zwischen Gegenwartsbrauch und Marketing (Pumpkin, commerce and cult: Halloween and the pumpkin festival between contemporary custom and marketing), published in “Folklore Suisse” in 2010.

A pioneering role was played by the publicity-savvy Jucker brothers in canton Zurich, whose farm soon became known throughout Switzerland for pumping out pumpkins and holding events such as competitions for the biggest pumpkin pyramid, the biggest pumpkin soup, the heaviest pumpkin and so on. The media lapped this up, and countless farmers followed their example and flooded Switzerland with pumpkins, which until then had been eaten sparingly but which now filled home kitchens and restaurants.

In 1991, 230 tonnes of pumpkins were sold in Switzerland. By 2000, it was around 10,000 tonnes, according to this SWI swissinfo.ch article from 2001.

“The Juckers took advantage of the traditional November gap in the event sector, so that in addition to the major retailers, amusement parks, catering establishments and costume shops also showed interest and achieved high sales,” Kuhn said.

‘Prowling youths’However, it appears that Halloween then took a slight hit. Halloween sales at the country’s two biggest supermarkets, Migros and Coop, plummeted in 2007.

At the same time, media coverage of Halloween changed, Kuhn said. “While earlier there had been favourable reports and Halloween had even made it onto daytime television, now the focus was mainly on the damage to property committed during the night by prowling youths”.

In 2021, Lausanne newspaper Le MatinExternal link said the police were well aware that little monsters for one evening can really be just that: little monsters.

“In recent years, more and more people have had the unpleasant surprise of finding eggs thrown at the front of their house or windows,” it said. “While the threat of ‘trick or treat’ is supposed to be no more than a threat, some children really do take revenge on those who don’t give them anything or open the door for them.”

The police pointed out that participation in Halloween “is not compulsory” and that refusal shouldn’t lead to reprisals, “however harmless they may seem”.

Zombie partiesToday, October 31 means Swiss department stores offering “Halloween deals”, restaurants still throwing pumpkin into everything, and cinemas showing classic horror films.

“Playing with spooky things is catching on in ever wider circles,” reckoned the St. Galler TagblattExternal link on Tuesday. “Many people have fun with it, organising Halloween parties where they walk through the living room dressed up as zombies with a glass of blood-coloured liquid and dip tortilla chips into guacamole ‘vomited up’ from a pumpkin.”

While Halloween in Switzerland is still far from the massive national celebration it is in the United States, those Swiss who celebrate it really go for it, with adults seemingly trying to outdo each other with impressively gory make-up.

Costumes in the US are generally more humorous or satirical, but the Swiss have a chance to do satire during the carnival season. It should also be pointed out that the Swiss are no strangers to eyebrow-raising customs, such as decapitating a dead goose or holding down young girls and putting blackface on them:

And as Kuhn noted, elements of Halloween can be found in other customs that are widespread in Switzerland, such as the carved turnip with a candle as in the Räbeliechtli procession, asking for something at the front door as in carol singing, or the elements of commemorating the dead on All Saints’ Day.

As for whether Halloween is gaining or losing popularity in Switzerland, it’s hard to say. Some neighbourhoods put on well-organised parties for adults and are teeming with skeletons and witches. Social media enables parents to create maps of which houses are tricking or treating. Other streets are dead.

But Kuhn was confident that the tradition would continue in some form. “The need for a yearly cycle shaped by highlights continues, so it can be assumed that Halloween […] will be innovatively integrated into the existing customs landscape”.

The pumpkin, he added, also seems to have found its place beyond Halloween parties by being carved as a family and then put on display: “a family custom during the dark season”.

This article was originally published on October 31, 2023.

https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/culture/how-halloween-became-part-of-swiss-culture/48939508

==================

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 31 Oct 2025 - 6:02pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

swiss PS....

EU ban on state aid and Swiss public service – like fire and water

by Dr iur. Marianne Wüthrich

On 9 September 2025, the National Council voted overwhelmingly in favour of a “reliable, comprehensive and high-quality” basic postal service “for the entire population” by 151 votes to 33, with 11 abstentions. The lower house of parliament is thus opposing the Federal Council’s austerity plans: Its draft postal ordinance “provides for home delivery to be limited to settlements with at least five houses per hectare or a maximum delivery time of two minutes. What does that mean in concrete terms? Individual farms, scattered settlements and entire rural regions would lose their home delivery service.” (David Roth, SP LU, on behalf of the commission). Roth adds: “I know that it would of course be cheapest for the Post Office if we all collected our letters in Härkingen [mail centre] or our parcels in Mülligen [parcel centre]. But that is not the idea of basic service provision. Basic service provision means that the Post Office comes to the people, not the other way round”.1 A wonderfully true-to-life description of what we Swiss understand by public service!

As if from another planet

In comparison, the EU’s ban on state aid, which would apply to agreements on land transport, electricity and air transport, seems like something from another planet, both in terms of content and style:

“Article 3 State aid. 1. Save as otherwise provided in the Agreement, any aid granted by Switzerland or by a Member State of the Union, or through State resources in any form whatsoever, which distorts or threatens to distort competition by favouring certain undertakings or the production of certain goods shall, in so far as it affects trade between the Contracting Parties within the scope of the Agreement, be incompatible with the proper functioning of the internal market.”2

The protocol does list a few exceptions, couched in the usual bureaucratic language, which means they are not really comprehensible to you and me. But the fact remains that the EU ban on state aid – whatever exceptions it may contain – and the Swiss understanding of the state are as different as chalk and cheese, as are many other things that come out of Brussels.

Unacceptable downplaying by the Federal Council

In its fact sheet on state aid dated 13 June 2025, the Federal Council once again plays down the serious consequences of the framework agreement to the point of absurdity: “Public services will remain in place. They are also permitted in principle in the EU. In addition, there are thresholds and numerous exceptions”.3And so on in this vein – we will spare our readers the rest. One could easily think that the EU ban on state aid ended up in the agreements on land transport, electricity and air transport by mistake.

Far-reaching consequences of EU state aid law for Switzerland

In contrast, Philipp Zurkinden, professor of law at the University of Basel, pointed out two years ago that “the EU concept of state aid is unknown in the Swiss economic and legal system and that adopting EU state aid law would have far-reaching consequences for Switzerland.” This is because Swiss subsidy law is not concerned with competition, but with the sensible, effective and fair use of public funds, for example to promote electricity production. Zurkinden warns: “Under EU state aid law, individual subsidy measures of this kind would not be permissible if they resulted in distortions of competition.”4

Whether the EU bodies will tolerate favourable loans for Swiss Federal Railways(SBB) or cantonal tax breaks for new companies or – even more seriously (!) – the prevention of the privatisation of hydroelectric power plants or public transport by the electorate will ultimately be decided by the ECJ and the EU Commission. And they tend to gear their competition policy more towards the wishes of large corporations than towards the interests of their member states or even Switzerland.

A recent example: in December 2024, the National Council and Council of States approved rapid assistance for the struggling steelworks in Gerlafingen and Emmenbrücke, as well as two aluminium plants in Valais. To enable them to survive despite cheap competition from the EU, they will receive temporary special discounts for using the electricity grid. Would the EU allow such state subsidies?

Two years ago, the trade unions, as guardians of good public services for all, spoke plainly. Benoît Gaillard, spokesperson for the Swiss Trade Union Federation (SGB), warned that “the EU state aid rules that Switzerland would have to adopt also jeopardise Swiss public services in rail freight and passenger transport”. SGB economist Reto Wyss reported on how the French state-owned freight railway Fret SNCF was threatened: “After the EU Commission ruled that subsidising the railway was inadmissible, the government decided to split it up in order to avoid impending fines and repayments amounting to billions.”5

Integration into the EU surveillance system: Switzerland as an assisting agent

The icing on the cake: Switzerland is actually “allowed” to monitor compliance with EU state aid rules on its own territory! However, this must be done in accordance with meticulous guidelines from Brussels, i.e., as an agent of the European Commission. To this end, it must “establish and maintain a state aid surveillance system that ensures at all times a level of surveillance and enforcement equivalent to that applied in the Union, as set out in paragraph 2 [...]” (Art. 4(3) of the Protocol on State Aid). All alarm bells should ring when we read in Art. 5(4): “All existing aid schemes in Switzerland shall be subject to constant review by the surveillance authority as to their compatibility with the proper functioning of the internal market pursuant to paragraphs 5, 6 and 7.” (emphasis added)

Which public services will the Swiss authorities classify as compatible “with the proper functioning of the internal market”? It is to be hoped that the trade unions and other critical voices will make themselves heard in the ongoing consultation process and tear the whole construct apart. •

https://www.zeit-fragen.ch/en/archives/2025/nr-22-14-oktober-2025/eu-beihilfeverbot-und-schweizer-service-public-wie-feuer-und-wasser