Search

Recent comments

- naked.....

45 sec ago - darkness....

14 min 40 sec ago - 2019 clean up before the storm....

5 hours 34 min ago - to death....

6 hours 13 min ago - noise....

6 hours 20 min ago - loser....

9 hours 51 sec ago - relatively....

9 hours 23 min ago - eternally....

9 hours 28 min ago - success....

19 hours 57 min ago - seriously....

22 hours 40 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

a movement of million of people needed.....

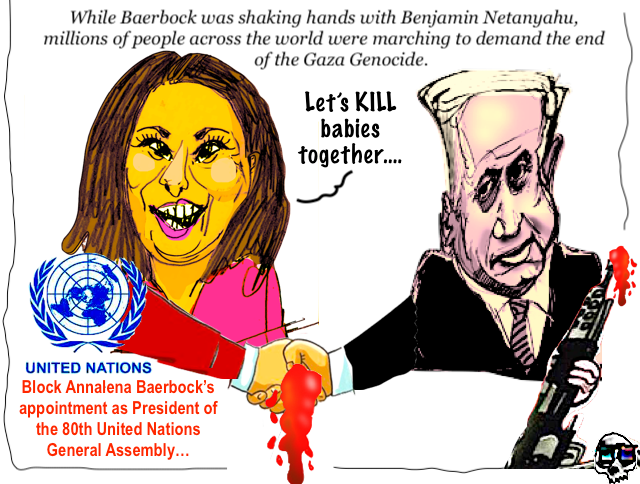

The clock is ticking to block Annalena Baerbock’s appointment as President of the 80th United Nations General Assembly.

The UN General Assembly is meant to represent the world’s majority.

But while Baerbock was shaking hands with Benjamin Netanyahu, millions of people across the world were marching to demand the end of the Gaza genocide.

A criminal like Baerbock does not — and must not — represent us.

Baerbock justified attacks on civilians under the guise of “self-defense”

Baerbock blocked ceasefire efforts as Israel devastated Gaza

Baerbock refused to enforce arrest warrants for Israeli officials implicated in crimes against humanity

Baerbock attacked South Africa’s ICJ case against Israel, rejecting it as "baseless" despite the court’s findings

Baerbock authorized over €400 million in military exports to Israel in 2023 alone

Only a movement of millions will be powerful enough to block this shameful appointment.

SIGN THE PETITION.....

https://act.progressive.international/block-baerbock/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 9 Jul 2025 - 3:55pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

slow murder.....

‘My journey to get aid in Gaza was like Squid Game’

Going to the US-backed aid distribution centre was the hardest day of my life. I’ve never felt humiliation like that

[MEE] Editor’s note: The following personal account of Yousef al-Ajouri, 40, was told to Palestinian journalist and MEE contributor Ahmed Dremly in Gaza City. It has been edited for brevity and clarity.

My children cry all the time because of how hungry they are. They want bread, rice - anything to eat.

Not long ago, I had stockpiles of flour and other food supplies. It’s all run out.

We now rely on meals distributed by charity kitchens, usually lentils. But it’s not enough to satisfy the hunger of my children.

I live with my wife, seven children, and my mother and father in a tent in al-Saraya, near the middle of Gaza City.

Our home in Jabalia refugee camp was completely destroyed during the Israeliarmy’s invasion of northern Gaza in October 2023.

Before the war, I was a taxi driver. But due to shortages in fuel, and the Israeli blockade, I had to stop working.

I hadn’t gone to receive aid packages at all since the war started, but the hunger situation is unbearable now.

So I decided I would go to the American-backed Gaza Humanitarian Foundationaid distribution centre on Salah al-Din Road, near the Netzarim corridor.

I heard that it’s dangerous and people were getting killed and injured, but I made the decision to go anyway.

Someone told me that if you go once every seven days, you might get enough supplies to feed your family for that week.

Dark and deadly routeIt was around 9pm on 18 June when I heard men in the next tent preparing to head out to the aid centre.

I told my neighbour in the next tent, Khalil Hallas, aged 35, that I wanted to join.

Khalil told me to get ready by wearing loose clothes, so that I could run and be agile.

He said to bring a bag or sack for carrying canned and packaged goods. Due to overcrowding, no one was able to carry the boxes the aid came in.

My wife Asma, 36, and my daughter Duaa, 13, encouraged me to make the journey.

They’d seen in the news that women were going to get aid too, and wanted to join me. I told them it was too dangerous.

I set off with five other men from my camp, including an engineer and a teacher. For some of us, it was the first time making the trip.

We rode in a tuk-tuk - the only means of transport in southern Gaza, along with donkey and horse-drawn carts - with a total of 17 passengers. It included children aged 10 and 12.

A young man in the vehicle, who had made the trip before, told us not to take the official route designated by the Israeli army. He said it was too crowded and we wouldn’t receive any aid.

He advised us to take an alternative route not far from the official path.

The tuk-tuk dropped us off in Nuseirat, in central Gaza, and from there we walked around a kilometre towards Salah al-Din Road.

The journey was extremely difficult - and dark. We couldn’t use any flashlights, or else we would attract the attention of Israeli snipers or military vehicles.

There were some exposed, open areas, which we crossed by crawling across the ground.

As I crawled, I looked over, and to my surprise, saw several women and elderly people taking the same treacherous route as us.

At one point, there was a barrage of live gunfire all around me. We hid behind a destroyed building.

Anyone who moved or made a noticeable motion was immediately shot by snipers.

Next to me was a tall, light-haired young man using the flashlight on his phone to guide him.

The others yelled at him to turn it off. Seconds later, he was shot.

He collapsed to the ground and lay there bleeding, but no one could help or move him. He died within minutes.

Some nearby men eventually covered the man’s body with the empty bag he had brought to fill up with canned goods. I saw at least six other martyrs lying on the ground.

I also saw wounded people walking back in the opposite direction. One man was bleeding after falling and injuring his hand in the rough terrain.

I fell a few times too. I was terrified, but there was no turning back. I’d already passed the most dangerous areas, and now the aid centre was within sight.

We were all afraid. But we were there to feed our hungry children.

Fighting for foodIt was coming up to 2am, which is when I was told access to the aid centre is granted.

Sure enough, moments later, a large green light lit up the centre in the distance, signalling that it was open.

People started running towards it from every direction. I ran as fast as I could.

I was shocked by the massive crowd. I’d risked my life to get closer to the front, and yet, thousands had somehow arrived before me.

I started questioning how they got there.

Were they working with the military? Were they collaborators, allowed to reach the aid first and take whatever they wanted? Or had they simply taken the same, if not even greater, risks that we had?

I tried to push forward, but I couldn’t. The centre was no longer visible because of the size of the crowds.

People were pushing and shoving, but I decided I had to make it through - for my children. I took my shoes off, put them in my bag, and began forcing my way through.

There were people on top of me, and I was on top of others.

I noticed a girl being suffocated under the feet of the crowds. I grabbed her hand and pushed her out.

I started feeling around for the aid boxes and grabbed a bag that felt like rice. But just as I did, someone else snatched it from my hands.

I tried to hold on, but he threatened to stab me with his knife. Most people there were carrying knives, either to defend themselves or to steal from others.

Eventually, I managed to grab four cans of beans, a kilogram of bulgur, and half a kilogram of pasta.

Within moments, the boxes were empty. Most of the people there, including women, children and the elderly, got nothing.

Some begged others to share. But no one could afford to give up what they managed to get.

Even the empty cartons and wooden pallets were taken, to be used as firewood for cooking.

Those who got nothing started picking up spilled flour and grains from the ground, trying to salvage what had fallen during the chaos.

Soldiers watched and laughedI turned my head and saw soldiers, maybe 10 or 20 metres away.

They were talking to each other, using their phones, and filming us. Some were aiming weapons at us.

I remembered a scene from the South Korean TV show Squid Game, in which killing was entertainment - a game.

We were being killed not only by their weapons but also by hunger and humiliation, while they watched us and laughed.

I started wondering: were they still filming us? Were they watching this madness, seeing how some people overpowered others, while the weakest got nothing?

We left the area just as the boxes had emptied.

Minutes later, red smoke grenades were thrown into the air. Someone told me that it was the signal to evacuate the area. After that, heavy gunfire began.

Me, Khalil and a few others headed to al-Awda Hospital in Nuseirat because our friend Wael had injured his hand during the journey.

I was shocked by what I saw at the hospital. There were at least 35 martyrs lying dead on the ground in one of the rooms.

A doctor told me they had all been brought in that same day. They were each shot in the head or chest while queuing near the aid centre.

Their families were waiting for them to come home with food and ingredients. Now, they were corpses.

I started to break down, thinking about these families. I thought to myself: why are we being forced to die just to feed our children?

At that moment, I decided that I would never journey to those places again.

A slow deathWe walked back in silence, and I arrived home at around 7:30am on Thursday morning.

My wife and children were waiting for me, hoping that I was safe and alive, and that I’d brought back food.

They were upset when they saw I’d returned with barely anything.

It was the hardest day of my life. I’ve never felt humiliation like I did that day.

I hope food can get through soon and be distributed in a respectful way, without humiliation and killing. The current system is chaotic and deadly.

There’s no justice in it. Most end up with nothing, because there’s no organised system and there’s too little aid for too many people.

I’m certain Israel wants this chaos to continue. They claim this method is best because, otherwise, Hamas takes the aid.

But I’m not Hamas, and many, many others aren’t either. Why should we suffer? Why should we be denied aid unless we risk our lives to get it?

At this point, I don’t even care if the war keeps going - what matters is that food gets through, so we can eat.

My son, Yousef, is three years old. He wakes up crying, saying he wants to eat. We have nothing to give him. He keeps crying until he gets tired and falls silent.

I eat one meal a day, or sometimes nothing at all, so the children can eat.

This isn’t life. This is a slow death.

https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/my-journey-aid-gaza-like-squid-game

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

murdered for food....

Gaza: UN says nearly 800 killed near aid centers since May

John Silk AFP, Reuters, dpa

The OHCHR released figures that showed at least 798 people have been killed trying to access aid in the Gaza Strip over the past 10 weeks. The much-maligned GHF have cast doubt on the veracity of the numbers.

The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) reported on Friday that at least 798 people have been killed trying to access aid in the Gaza Strip since the end of May.

Of those deaths, 615 were recorded at or near humanitarian aid distribution hubs operated by the US and Israeli-backed Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF), according to UN human rights spokeswoman Ravina Shamdasani.

Another 183 people had been killed "presumably on the routes of aid convoys" conducted by United Nations and other aid organizations, she told reporters in Geneva, where one of the four major UN offices is located.

"This is nearly 800 people who have been killed while trying to access aid," she said. "Most of the injuries are gunshot injuries," she added.

What's the role of the GHF?GHF operations, which effectively sidelined a vast UN aid delivery network in Gaza, have been blighted by chaotic scenes and near-daily reports of Israeli forces firing on civilians who are trying to receive aid.

The figures from the UN were reported as at least 10 more people were reportedly killed on Friday near an aid distribution site in Rafah, a city in the southern Gaza Strip.

About 70 other people were wounded in the incident, the Hamas-controlled Gaza health authority reported.

What about a possible ceasefire?This all comes as negotiators from Israel and the Palestinian militant group Hamas — which is classified as a terrorist organization by the German government, the EU, the US and some Arab states — are locked in indirect talks in Qatar about a possible ceasefire.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Thursday that he hoped a deal for a 60-day halt in hostilities could be agreed upon in the coming days.

The GHF, which began distributing food packages in Gaza in late May after Israel lifted an 11-week aid blockade, told the Reuters news agency that the UN figures were "false and misleading."

"The fact is the most deadly attacks on aid site have been linked to UN convoys," a GHF spokesperson said.

"Ultimately, the solution is more aid," the spokesperson said. "If the UN (and) other humanitarian groups would collaborate with us, we could end or significantly reduce these violent incidents."

What has been the UN reaction to the doubts cast by the GHF?The OHCHR said it based its figures on sources such as data from hospitals in Gaza, cemeteries, families, Palestinian health authorities, NGOs and its partners on the ground.

Shamdasani said most of the injuries to Palestinians in the vicinity of aid distribution hubs since May 27 were caused by gunshots.

She said there was particular concern about "atrocity crimes being committed where people are lining up for essential supplies such as food."

In response to the GHF's casting doubt on the OHCHR figures, Shamdasani said: "It is not helpful to issue blanket dismissals of our concerns — what is needed is investigations into why people are being killed while trying to access aid."

Israel says its forces operate around the aid sites to prevent supplies from falling into the hands of militants.

https://www.dw.com/en/gaza-un-says-nearly-800-killed-near-aid-centers-since-may/a-73247495

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

US "help".....

In Gaza, U.S. Mercenaries Advance Israeli War Aims

Kelley Beaucar VlahosWashington is farming out private military contractors to Israel. What could go wrong?

The world watched as the beaten and burned bodies of four American contractors from a private military company, then known as Blackwater, swung from a bridge over the Euphrates River in Iraq.

It was March 31, 2004. Iraqi fighters had ambushed the U.S. mercenaries, proving beyond doubt the deadly seriousness of an insurgency that the U.S. government did not anticipate when it invaded Baghdad and deposed Saddam Hussein a year earlier. The episode sparked the first and then second battles of Fallujah, which resulted in over 120 U.S. Marines and upwards of 1,500 civilians killed and entire neighborhoods bombed out after extensive block-to-block fighting with insurgents.

Fast forward to today as the world watches images of beefed-up American contractors hailing from opaque companies called UG Solutions and Safe Reach Solutions shooting off guns at a security perimeter in one of the most nightmarish hellscapes on earth: the Gaza strip. They reportedly make $1100 a day after a $10,000 signing advance. The fact that they are there at all raises a host of questions, not least of which is what happens when one of them shoots into a crowd and kills a civilian, or when one of them is attacked—maybe dragged away, hung off a bridge.

The Trump administration has been virtually silent on the deployment of mercenaries to Gaza—first to help secure checkpoints in Gaza as part of a “multinational consortium” in February, and more recently to provide perimeter security for the U.S.-based Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF), the controversial outfit (conceived of and backed by Israel and the U.S with its own CIA link) serving as the primary channel for food aid to starving Palestinians. Over 500 civilians have been killed at these desolate aid centers, reportedly by IDF fire, in the last month.

Gazans are walking for miles to four Mad Max-like facilities at the borders of the strip in the South and at the Netzarim corridor, which splits the north and south in half and has been occupied if not fortified by the IDF since the war began in October 2023, shortly after the Hamas attacks on Israel.

The AP reported last week that two of the U.S. contractors from Safe Reach Solutions came forward as whistleblowers under the condition of anonymity and accused colleagues of shooting into crowds with live ammo, stun grenades, and pepper spray. Videos show Gazans forced like cattle into narrow, trench-like lines bordered by tall metal fences to queue up for food. There is mayhem. In one video, as machine-gun fire is heard in the vicinity, one American voice says, “I think you hit one.” Another yells, “hell yeah, boy!”

Safe Reach Solutions and the GHF have both denied that the hired guns were shooting into the crowd, though Safe Reach has acknowledged that live ammo has been used “in scattered incidents” away from crowds “to get [civilians’] attention.” The GHF said the gunfire in the video was coming from IDF soldiers and not directed into the crowds.

Several military and contracting experts who spoke with The American Conservative (TAC) say the U.S. is at a dangerous crossroads. The war privatization trend—which exploded during the post-9/11 conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and North Africa—has metastasized and morphed into a situation in which mercenaries are used as an extension of the U.S. government to directly advance a foreign nation’s war policy. The “humanitarian” justification, they say, is a fig leaf.

Western media and analysts have maligned Russia’s state-funded private military company (PMC), the Wagner Group, for fighting on behalf of but not officially for Moscow in Syria, Ukraine, and Africa. Now, it’s becoming clear that American companies, like UG Solutions and Safe Reach, run and staffed by ex-U.S. military and CIA paramilitary, may be smaller than Wagner but are similar in organization. While there is currently no overt federal funding trail to the contractors, both of which appear to have sprung into existence recently (and have not returned TAC’s calls for comment), the State Department rushed $30 million in USAID funds to GHF in the last month, waiving audits to do it.

“A colleague and I used to ruminate at times on the coming ‘Wagnerization’ of U.S. security policy, noting that Wagner offers a flexible, quasi-deniable, and politically expedient policy instrument to the Russian government,” said Richard Hinman, retired foreign service officer with the State Department as well as a retired Army officer who served in several U.S. conflict zones.

“The immediate advantages are just too compelling for a U.S. administration looking at a four-to-eight-year run,” Hinman told TAC. “It may be a bad idea, but it has a pretty slick selling point. So we can see GHF as a step on the path toward a U.S.-style Wagnerization.”

The selling point? Trump doesn’t have to put “boots on the ground.” Rather, he just farms out assistance to further the Israeli government’s plan for Gaza, which according to reports this week, is to continue to make the rest of the strip uninhabitable while shifting hundreds of thousands of half-starved and homeless Gazans into a giant camp with the Orwellian name “humanitarian city,” built on the ruins of Rafah in the south. Next, the Palestinians will have a “free choice” to migrate out of Gaza, says Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Having Americans manning checkpoints and the inner ring of the GHF centers puts a “multinational” face on what is essentially an IDF operation.

Josh Paul, a former military affairs official in the State Department who resigned his post in 2023 in protest of Biden’s policies of transferring weapons to Israel, told TAC that the U.S. contractors in Israel, like all hired guns, allow “a degree of separation” in that they “don’t imply (U.S.) national involvement.” Still, Paul says, “it is clear they are there with U.S. approval and a deep complicity” in what is taking place at these aid centers, including the deaths of hundreds of civilians.

While this is worrying on several different levels, the actual hired guns don’t seem too concerned. They were hired to do a job, said Morgan Lerette, a former PMC and the author of Guns, Girls, and Greed: I Was a Blackwater Mercenary in Iraq. In the Iraq war, contractors “draped themselves in the flag” and insisted they weren’t mercenaries because they were serving as bodyguards for the State Department, he said. “The Gaza contract has changed the entire paradigm. They try to say they are trying to get food to people, but this is 100 percent mercenary work.”

The contractors don’t care about “the strategy or the politics or anything but surviving another day to make their $1500,” he said. “But what you are doing is putting people in situations where they have to make snap judgements, and there is so much legal ambiguity of what they can do or can’t do,” he told TAC.

“This feels like a huge step in private military contracting. It was one thing to work under the State Department, but it is a whole different to work for a foreign government entity in a foreign land in an active combat.”

Of course, American PMCs have been working across the globe for decades now to help fragile governments raise and train armies and to engage in humanitarian and rescue missions. In many ways, the proliferation of mercenaries—what former contractor and author Sean McFate calls “neomedievalism”—is the direct result of their overuse by the U.S. in the Middle East to this day. There is a supply—a lot of ex-soldiers and contractors with training—and a demand—fragile states in conflict with leaders willing to spend the coin.

Gaza has accelerated the trend for Washington, which supports Israel’s assault on the strip but governs a population with red lines about putting American men and women in a warzone. The Israeli government surely welcomes any help it can get. Its military—mostly reserves—is stretched thin, and the Netanyahu government needs to manage optics while sustaining a crushing military operation on the ground. U.S. mercenaries aren’t (yet) fighting in Gaza, but in a way the political decision to use them is not dissimilar from Moscow deploying Wagner in Ukraine or bringing in North Koreans to fight in the Kursk region of Russia.

“Though we are not quite there yet, the trend that we are observing seems to be moving toward the outsourcing of certain types of military activities and operations to private companies, often staffed with veterans, to get around rules and limits placed on the use of U.S. military forces,” Jennifer Kavanagh, military affairs analyst for Defense Priorities, tells TAC. “Gaza is the next iteration.”

https://www.theamericanconservative.com/in-gaza-u-s-mercenaries-advance-israeli-war-aims/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

racism...

by Rick Sterling | Jul 13, 2025 | News | 0 Comments

The following interview was conducted by Rick Sterling on June 30, 2025. This is the first in a series of interviews of Anti-Zionist Jewish Americans.

Marvin Cohen is a longtime member and former board member of the Mt. Diablo Peace & Justice Center in Contra Costa, California. In 2010 he co-founded the Rossmoor club known as Voices for Justice in Palestine. The club is very active and hosts educational and fundraising events every month.

Q: Where did you grow up and where do you live now?

A: I grew up in Brooklyn, New York, beginning in 1937. Right now, I’m living in Rossmoor, an adult community in Walnut Creek, California. And I’ve been here for 20 years in this community.

Q: When you were growing up, did you encounter discrimination or antisemitism?

A: I’d have to say very, very little to me personally. I can’t think of any at all. When my father stopped working in the shipyards in San Francisco as a draftsman, when they stopped building all the Liberty ships, he was trying to get a job with a good company in San Francisco. He didn’t get it. And he was really an excellent draftsman. And I think at that time, 1946, it’s probably pretty safe to say that it was antisemitism. By the way, later in his life, he got a job as a draftsman working for NASA. So he was obviously a very competent artist and draftsman.

As for me, come to think of it, the only antisemitism I experienced was right here in this community. And it came from zionist Jewish people.

Q: What do you mean? Could you explain that?

A: I received a lot of hate mail from the zionists, telling me that I’m a traitor and a self-hating Jew and things of that nature. They slandered me and vandalized my car because I’m a Jewish person, especially a Cohen, and against Israeli policy. I can’t help it. I’m against injustice. I feel sorry for those people. They’re so full of hate.

When I was very young, I had a very close friend named Alex Weiss. He and his family came from Europe. They barely escaped with their lives from Austria. And when we were six years old, living in the Fillmore District in San Francisco, we were busted by the police because we were throwing dirt clogs at streetcars, imagining that they were Nazi tanks, and we were winning the war against the Nazis. Alex was a Holocaust survivor with his family: his father,mother, and sister. They lost almost everything they had. They were an upper middle class family in Austria, and they barely escaped.

Alex had a big influence on me. He was like an older brother, and he was totally against injustice anywhere. When he was in his early twenties, he got busted in Mississippi because he was a freedom rider. Later, he helped to save the prison on Angel Island when he was a state park ranger there. They were going to destroy the evidence of having had all these Asian people in jail on Angel Island, and he said, “No, that’s injustice. An injustice to anyone is not fair. We’re all human beings.”

So that was my buddy Alex.

Q: I know that you spent some time in Israel; you migrated to Israel at one point. What was your experience there?

A: Well, I went there when I was 40 years old. My wife at that time and I were living on Sonoma Mountain, about an hour north of San Francisco. I had previously worked as a school counselor for the San Francisco schools. One Sunday, I saw an advertisement in the Sunday Chronicle: the Israeli government was looking for school counselors. That sounded like a really interesting adventure. I had never been there, and my Italian-American wife knew I liked languages. I already spoke Italian and Spanish, and oh, I could learn Hebrew. I had Hebrew when I was 12 years old for my bar mitzvah. But that’s not the same as speaking fluently with the people that you’re working with. So I went to Israel to work as a school counselor. I was living in Ashkelon about eight miles up the coast from Gaza and living there with a bunch of other immigrants who were learning to speak Hebrew. This was called an absorption center. There were Jewish immigrants from all over the world, but the majority of them were Russian. So, six hours a day, six days a week, we had intensive Hebrew lessons.

And that was all fine. I was doing just fine. There were some Jewish holidays along the way, and for me, that meant free time because I was not into going to a synagogue. I finished with my Judaism when I was Bar Mitzvah at 13.

So the holy days were an opportunity to travel around a little bit. It’s not a big place. So I went to Jerusalem a couple of times. I went to Jericho; I went to the Sinai. And in Jericho – Wow. I had such an experience with a Palestinian family in Jericho. I was so impressed with the warmth of these people.

Living in Ashkelon and being busy six days a week, six hours a day, learning Hebrew, I had a little bit of free time. So meeting these Palestinian people was really something. It started opening up my eyes to the terrible reality of how life is there in Israel. And I didn’t like what I was seeing there.

Then I had another experience at the Dome of the Rock, the beautiful mosque with the gold dome that you often see in photos of Jerusalem. So I went in and sat down. There were about 30 people sitting down with their eyes closed in meditation. I sat down and was in meditation for 10 or 15 minutes. When I opened my eyes, I was looking into the eyes of a guy across from me. And we kind of nodded to each other. He was wearing glasses like me. He had a beard like me. He was balding like me, and we just nodded to each other. I got up to leave, and as I’m outside putting my shoes on, he came out and was putting his shoes on, and he started a conversation with me. He looked Arab, probably Palestinian, but he spoke really good English. I only knew a couple of words of Arabic. So he said, “Hello, my name is Marwan. What’s your name?” I thought it was funny that he’s Marwan and I’m Marvin. So we both got a kick out of that. He says, “So you don’t look like you’re from around here.” I said, “No, I’m not.” Maybe he thought I was not from around. I had a long ponytail at that time; I don’t think too many people around at that time had long ponytails. So I said, “Well, yeah, I’m from the USA.” He said, “Really? Where in the USA?” I said, “Well, Brooklyn, New York. Actually, I was born there in ’37.”

And he says, “’37? , you were born in 1937?” I said, “Yeah. He says, “I was also born in 1937.” We thought that was pretty funny. He says, “So where do you live now?” I said, “I live here. I live in Ashkelon.”

He says, “You live in Ashkeon? You left San Francisco to live in Ashkeon?” I said, “Yeah. He says, “Why would you want to live in Ashkeon when you’re living in San Francisco? Everyone wants to go to San Francisco and see the Golden Gate Bridge.” So I said, “Well, actually, I went there for work. I went there to work as a school counselor.” And he gets really wild-eyed and starts laughing. I said, “What’s funny about that?” And he says, “I’m a high school counselor in Gaza.” I thought, “Are you kidding me? That blew me away.” So then I said, “Wow. I am only eight miles north of where you are, and I just got my bicycle delivered from San Francisco, and I’ve been bicycling. Whenever I get a chance, I go bicycling. I go bicycling to a nice beach that I know up north. But I’d like to bicycle down and visit you in your high school. And he was silent. And then he said, “That might not be a good idea.”

And that just pointed out to me how ridiculous this whole thing is.

Q: What year was that?

A: That was in 1977. If you look back in history, I was living there when Anwar Sadat, the president of Egypt, visited Jerusalem, and it was a really big deal. There were Egyptian flags all over the place, and of course, they did away with Sadat. They don’t like anyone who’s trying to make peace. That was in 1977, I was 40 years old.

Do you know why he thought it was not a good idea for you to visit Gaza?

A: Well, he was thinking that there are some people in Gaza who don’t have really good feelings about what Jewish people have done. I could understand that, but that hit me.

Q: So what is your hope for Israel-Palestine now?

A: Peace. Justice should be a real democracy for everyone. It’s just an incredible place on this planet. People all over this planet want to visit that place. Three huge religions that are important to so many people in the world, and people around the world want to visit that area because of that. And it’s not big. It’s easy to get around. And the weather’s kind of neat. Living in Ashkelon was kind of similar to San Diego because just a couple of miles inland from there, you have desert. But you have the ocean or Mediterranean right there with nice warm water.

Q: What do you think is the main thing holding back a solution?

A: Racism. That’s what Zionism is. A group of people that says they are superior. They’re superior to those people there. They believe, “We’re up here, we’re above everyone else. We’re better than all these other people. God told us. So we have rights. We can do what we want. We got a pass from God.” They’ve been getting away with murder, literally. Genocide, bombing, starving people. How crazier can you get than that?

Rick Sterling is an independent journalist in the San Francisco Bay Area. He can be contacted at [email protected]

Q: Where did you grow up and where do you live now?

A: I grew up in Brooklyn, New York, beginning in 1937. Right now, I’m living in Rossmoor, an adult community in Walnut Creek, California. And I’ve been here for 20 years in this community.

Q: When you were growing up, did you encounter discrimination or antisemitism?

A: I’d have to say very, very little to me personally. I can’t think of any at all. When my father stopped working in the shipyards in San Francisco as a draftsman, when they stopped building all the Liberty ships, he was trying to get a job with a good company in San Francisco. He didn’t get it. And he was really an excellent draftsman. And I think at that time, 1946, it’s probably pretty safe to say that it was antisemitism. By the way, later in his life, he got a job as a draftsman working for NASA. So he was obviously a very competent artist and draftsman.

As for me, come to think of it, the only antisemitism I experienced was right here in this community. And it came from zionist Jewish people.

Q: What do you mean? Could you explain that?

A: I received a lot of hate mail from the zionists, telling me that I’m a traitor and a self-hating Jew and things of that nature. They slandered me and vandalized my car because I’m a Jewish person, especially a Cohen, and against Israeli policy. I can’t help it. I’m against injustice. I feel sorry for those people. They’re so full of hate.

When I was very young, I had a very close friend named Alex Weiss. He and his family came from Europe. They barely escaped with their lives from Austria. And when we were six years old, living in the Fillmore District in San Francisco, we were busted by the police because we were throwing dirt clogs at streetcars, imagining that they were Nazi tanks, and we were winning the war against the Nazis. Alex was a Holocaust survivor with his family: his father,mother, and sister. They lost almost everything they had. They were an upper middle class family in Austria, and they barely escaped.

Alex had a big influence on me. He was like an older brother, and he was totally against injustice anywhere. When he was in his early twenties, he got busted in Mississippi because he was a freedom rider. Later, he helped to save the prison on Angel Island when he was a state park ranger there. They were going to destroy the evidence of having had all these Asian people in jail on Angel Island, and he said, “No, that’s injustice. An injustice to anyone is not fair. We’re all human beings.”

So that was my buddy Alex.

Q: I know that you spent some time in Israel; you migrated to Israel at one point. What was your experience there?

A: Well, I went there when I was 40 years old. My wife at that time and I were living on Sonoma Mountain, about an hour north of San Francisco. I had previously worked as a school counselor for the San Francisco schools. One Sunday, I saw an advertisement in the Sunday Chronicle: the Israeli government was looking for school counselors. That sounded like a really interesting adventure. I had never been there, and my Italian-American wife knew I liked languages. I already spoke Italian and Spanish, and oh, I could learn Hebrew. I had Hebrew when I was 12 years old for my bar mitzvah. But that’s not the same as speaking fluently with the people that you’re working with. So I went to Israel to work as a school counselor. I was living in Ashkelon about eight miles up the coast from Gaza and living there with a bunch of other immigrants who were learning to speak Hebrew. This was called an absorption center. There were Jewish immigrants from all over the world, but the majority of them were Russian. So, six hours a day, six days a week, we had intensive Hebrew lessons.

And that was all fine. I was doing just fine. There were some Jewish holidays along the way, and for me, that meant free time because I was not into going to a synagogue. I finished with my Judaism when I was Bar Mitzvah at 13.

So the holy days were an opportunity to travel around a little bit. It’s not a big place. So I went to Jerusalem a couple of times. I went to Jericho; I went to the Sinai. And in Jericho – Wow. I had such an experience with a Palestinian family in Jericho. I was so impressed with the warmth of these people.

Living in Ashkelon and being busy six days a week, six hours a day, learning Hebrew, I had a little bit of free time. So meeting these Palestinian people was really something. It started opening up my eyes to the terrible reality of how life is there in Israel. And I didn’t like what I was seeing there.

Then I had another experience at the Dome of the Rock, the beautiful mosque with the gold dome that you often see in photos of Jerusalem. So I went in and sat down. There were about 30 people sitting down with their eyes closed in meditation. I sat down and was in meditation for 10 or 15 minutes. When I opened my eyes, I was looking into the eyes of a guy across from me. And we kind of nodded to each other. He was wearing glasses like me. He had a beard like me. He was balding like me, and we just nodded to each other. I got up to leave, and as I’m outside putting my shoes on, he came out and was putting his shoes on, and he started a conversation with me. He looked Arab, probably Palestinian, but he spoke really good English. I only knew a couple of words of Arabic. So he said, “Hello, my name is Marwan. What’s your name?” I thought it was funny that he’s Marwan and I’m Marvin. So we both got a kick out of that. He says, “So you don’t look like you’re from around here.” I said, “No, I’m not.” Maybe he thought I was not from around. I had a long ponytail at that time; I don’t think too many people around at that time had long ponytails. So I said, “Well, yeah, I’m from the USA.” He said, “Really? Where in the USA?” I said, “Well, Brooklyn, New York. Actually, I was born there in ’37.”

And he says, “’37? , you were born in 1937?” I said, “Yeah. He says, “I was also born in 1937.” We thought that was pretty funny. He says, “So where do you live now?” I said, “I live here. I live in Ashkelon.”

He says, “You live in Ashkeon? You left San Francisco to live in Ashkeon?” I said, “Yeah. He says, “Why would you want to live in Ashkeon when you’re living in San Francisco? Everyone wants to go to San Francisco and see the Golden Gate Bridge.” So I said, “Well, actually, I went there for work. I went there to work as a school counselor.” And he gets really wild-eyed and starts laughing. I said, “What’s funny about that?” And he says, “I’m a high school counselor in Gaza.” I thought, “Are you kidding me? That blew me away.” So then I said, “Wow. I am only eight miles north of where you are, and I just got my bicycle delivered from San Francisco, and I’ve been bicycling. Whenever I get a chance, I go bicycling. I go bicycling to a nice beach that I know up north. But I’d like to bicycle down and visit you in your high school. And he was silent. And then he said, “That might not be a good idea.”

And that just pointed out to me how ridiculous this whole thing is.

Q: What year was that?

A: That was in 1977. If you look back in history, I was living there when Anwar Sadat, the president of Egypt, visited Jerusalem, and it was a really big deal. There were Egyptian flags all over the place, and of course, they did away with Sadat. They don’t like anyone who’s trying to make peace. That was in 1977, I was 40 years old.

Do you know why he thought it was not a good idea for you to visit Gaza?

A: Well, he was thinking that there are some people in Gaza who don’t have really good feelings about what Jewish people have done. I could understand that, but that hit me.

Q: So what is your hope for Israel-Palestine now?

A: Peace. Justice should be a real democracy for everyone. It’s just an incredible place on this planet. People all over this planet want to visit that place. Three huge religions that are important to so many people in the world, and people around the world want to visit that area because of that. And it’s not big. It’s easy to get around. And the weather’s kind of neat. Living in Ashkelon was kind of similar to San Diego because just a couple of miles inland from there, you have desert. But you have the ocean or Mediterranean right there with nice warm water.

Q: What do you think is the main thing holding back a solution?

A: Racism. That’s what Zionism is. A group of people that says they are superior. They’re superior to those people there. They believe, “We’re up here, we’re above everyone else. We’re better than all these other people. God told us. So we have rights. We can do what we want. We got a pass from God.” They’ve been getting away with murder, literally. Genocide, bombing, starving people. How crazier can you get than that?

Rick Sterling is an independent journalist in the San Francisco Bay Area. He can be contacted at [email protected]

https://www.antiwar.com/blog/2025/07/13/racism-thats-what-zionism-is/