Search

Recent comments

- success....

1 hour 1 sec ago - seriously....

3 hours 43 min ago - monsters.....

3 hours 51 min ago - people for the people....

4 hours 27 min ago - abusing kids.....

6 hours 40 sec ago - brainwashed tim....

10 hours 20 min ago - embezzlers.....

10 hours 26 min ago - epstein connect....

10 hours 38 min ago - 腐敗....

10 hours 57 min ago - multicultural....

11 hours 3 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the dutch roulette....

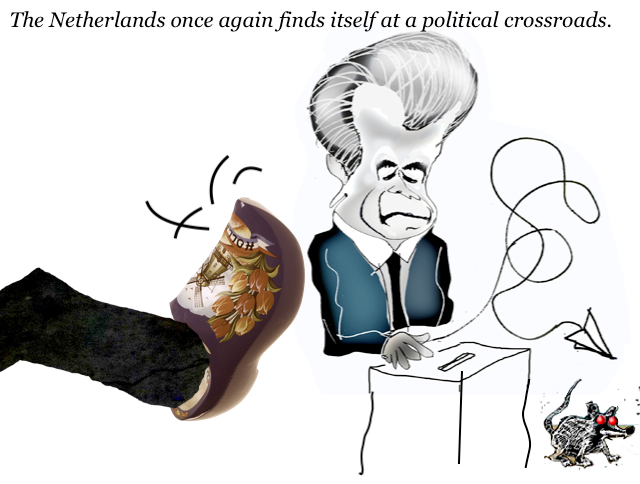

The Netherlands once again finds itself at a political crossroads. After years of turbulence and ideological fragmentation, the liberal-centrist party D66 (Democraten 66), led by Rob Jetten, scored a narrow yet striking victory compared with the previous election, rising from nine seats in 2023 to twenty-six in the 2025 snap election.

As Geert Wilders’ Far Right Stumbles, Can Rob Jetten’s Progressive Liberals Rebuild the Dutch Centre?

Ricardo Martins

It marks a spectacular turnaround for a country long defined by populism and political deadlock—from the thirteen years of centre-right rule under Mark Rutte’s VVD to the turbulent government of Geert Wilders’ far-right PVV, which won the election but, to form a coalition, had to appoint a technocratic prime minister rather than a figure from within the political establishment.

But as many Dutch people know, winning an election is only half the battle. The other half—forming a viable government—may prove far more difficult.

A Fragmented Political Landscape

For 13 years, the Netherlands was governed by Rutte’s VVD, steering a cautious centre-right course. Then came 2023, when Wilders’ PVV shocked Europe by winning the election and forming a short-lived coalition that soon collapsed over immigration disputes. Now, the political pendulum has swung back toward the centre, but with a fractured Parliament where no party holds a clear majority.

According to NOS reporting, the only viable coalition that reaches a majority of 86 seats would be a four-party mix “through the middle”: D66, VVD, GroenLinks–PvdA, and the Christian Democrats (CDA). The alternative “centre-right” combination—D66, VVD, CDA, and the right-wing JA21—falls short at 75 seats. This arithmetic already signals that coalition-building will be an intricate, if not precarious, process.

After years of populist noise, the Dutch electorate showed tiredness of Geert Wilders and may have rediscovered the quiet power of moderationD66’s Victory and What It Means

The D66 surge is widely interpreted as both a vote for optimism and a rebuke of far-right populism. The party’s message of inclusiveness, European cooperation, and pragmatic reform contrasted sharply with the PVV’s divisive rhetoric.

As Professor Henk van der Kolk of the University of Amsterdam explained, D66’s rise “was bigger than expected but not a complete surprise.” In the final days before the vote, he noted, a large share of voters moved to D66 “as the best way out of the negative context of the previous coalition.” Voters, he said, wanted stability and saw it in Jetten’s moderate, hopeful tone.

Yet van der Kolk also cautioned that this was not a rejection of the far right’s agenda. The total vote share of anti-immigration, climate-denying, and eurosceptic parties like PVV, JA21, and Forum voor Democratie still accounts for roughly 30% of Parliament. “We should not be misled by the PVV’s loss,” he said. “There remains a stable core of radical right-wing voters in the Netherlands.”

Edward Koning, Associate Professor at the University of Guelph, agrees. “The appetite for anti-immigrant populism in the Netherlands has not waned,” he observed. What has shifted is the perception of who can deliver results. Wilders’ failure to govern effectively and for having dropped out of his own coalition cost him credibility, while Jetten’s D66 became the credible alternative not for ideology, but for competence.

A Divided but Hopeful Electorate

Polls cited by Ipsos I&O show that 15% of voters wanted Jetten as prime minister, ahead of Wilders and Timmermans, and 21% rated him among the most cooperative leaders. His appeal is rooted in his tone as much as in his programme. As former D66 adviser Roy Kramer told NOS, “He doesn’t have much bravado, but he dares a lot. He’s calm, consistent, and takes on difficult issues.”

Jetten’s campaign focused on tangible priorities: housing (36%), climate action (28%), and asylum policy (15%). These are the issues, and the percentages, D66 voters said, mattered most in their choice.

Jetten’s message was simple: the Netherlands can choose optimism over outrage. For many Dutch citizens weary of Wilders’ combative politics, that was a refreshing alternative perceived by voters.

Still, polarisation persists. Former PVV politician Joram van Klaveren warned that while D66’s victory brings “a positive message,” the far-right bloc’s endurance shows that “we have a long way to go” before Dutch politics becomes less divisive.

The Coalition formation: the hard task

Forming a stable coalition is Jetten’s first challenge. As NOS reported, the first step was the appointment of Wouter Koolmees, a D66 committed and former minister, as “scout” to explore coalition options. The likely configuration—D66, VVD, CDA, and GroenLinks–PvdA—is Jetten’s preference, but convincing VVD leader Dilan Yeşilgöz to work with the left-wing bloc remains a major task.

The VVD favours a narrower “over-right” coalition including the far-right JA21, arguing it would be “more stable,” especially on asylum policy. But as analysts note, that would force Jetten to rely on a party openly hostile to his pro-EU, pro-climate, and inclusive agenda, a credibility risk for both him and D66.

“Forming is eliminating,” political reporter Lars Geerts explained in NOS’s De Dag podcast. Each party Jetten excludes narrows his options, but including the wrong one could cost him political trust. The Dutch tradition of coalition-building, Geerts noted, demands patience and diplomacy, traits Jetten is known to possess.

Europe, Foreign Policy, and the World Beyond

Beyond domestic concerns, this election carries symbolic weight in Europe. For the first time in years, the Netherlands could reassert itself as a constructive, pro-European voice after a decade of inward-looking governments.

Retired ambassador Kees Rade told me that a centre-left or centrist coalition “would most likely restore Dutch efforts in development assistance and multilateralism” and be “friendlier to Brussels.” Similarly, Kayle Van ’t Klooster of the Clingendael Institute said that while foreign policy barely featured in the campaign, “there is broad alignment across left and right for stronger European security cooperation.”

Still, few expect dramatic shifts. “Relations with the US and China will not be much impacted,” former Ambassador Rade noted, adding that both countries were “fully absent” from the campaign debates. Dutch foreign policy, he concluded, “will continue as usual, just a bit greener and more European.”

A Moment of Opportunity

In his final TV debate, Rob Jetten framed his appeal around optimism and cooperation: “Leadership through example,” he said, “in climate action, equality, and digital innovation.” At 38, he embodies generational renewal, the idea that Dutch politics can move past pessimism without ignoring reality.

Yet, as Henk van der Kolk reminded, “There is no clear coalition, not a coherent alternative either.” The road ahead will be difficult, and the far-right will eagerly exploit any weakness.

Still, there’s a sense that something shifted in this election. It is not a revolution, but a recalibration. After years of populist noise, the Dutch electorate showed tiredness of Geert Wilders and may have rediscovered the quiet power of moderation.

“Voters want us to stop the political hassle and put our shoulders together,” Jetten said on election night. His words might sound ordinary, but in today’s Netherlands—fragmented, polarised, and exhausted by conflict—they carry new weight.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 15 Nov 2025 - 10:51am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

political shake-up....

Lisanne Adam

From populism to progress: The Netherlands’ historic electionThe Netherlands has been at the centre of a political shake-up in recent weeks, with the vote count only just finalised.

For 24 hours after the polls closed, the election was too close to call. Now, the results are in: Rob Jetten’s D66, a liberal and progressive political party, has won the election by a margin of 29,668 votes, out of roughly 13.5 million eligible voters, ahead of Geert Wilders’ PVV, a far-right anti-immigration party.

This marks the tightest race in Dutch political history. Moreover, the apparent shift away from support for the far-right and anti-immigration policies could serve as an example for other European nations.

The rise and evolution of Dutch populism

The Netherlands prides itself on being a tolerant and welcoming society, yet it has also grappled with significant anti-immigration sentiment that fuelled the rise of Dutch populism. In the early 2000s, sociology professor Pim Fortuyn emerged as the country’s first prominent far-right populist, advocating for stricter immigration policies, particularly in relation to Muslims. He argued that such measures were necessary to protect Dutch culture and freedoms. Fortuyn’s slogan, “at your service”, quickly became widely recognised throughout Dutch society during this period.

Fortuyn’s political party, the LPF (‘List Pim Fortuyn’), rapidly gained popularity, but its strong right-wing populist advocacy was brought to an abrupt halt when Fortuyn was assassinated in May 2002. Remaining on the ballot as a posthumous candidate, Fortuyn’s LPF secured 26 out of 150 seats in Parliament during the 2002 election. However, due to significant internal conflict within the party, the LPF eventually ceased to exist in 2008.

Four years after the LPF’s major victory, Geert Wilders founded his Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV), or Freedom Party, in 2006. Mirroring the LPF’s approach, Wilders attributed many Dutch domestic problems to immigration, European Union regulations, and, most notably, to Islam. Despite widespread pushback and even a conviction for inciting hatred against the Dutch Moroccan population and other non- Western immigrants because of their race or ethnicity, Wilders’ party won the Dutch elections in 2023, securing 37 out of 150 seats.

Wilders chose Dick Schoof, a senior public servant, to serve as prime minister and formed a coalition committed to halting immigration. Wilders’ coalition attempted to declare an asylum crisis to block all incoming asylum applications and aimed to restrict the immigration of work migrants, disregarding the fact that some of his proposals violated European law.

Beyond legal concerns, Wilders and the PVV demonstrated little flexibility and proved unco-operative with other political parties, ultimately leading Wilders to withdraw from the coalition and trigger new elections, scheduled for 29 October 2025.

Navigating Fragmentation: D66’s Growth in a Changing Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary democracy. When Dutch citizens vote in national elections, they cast their ballots for a party on a national list rather than for candidates from local districts. The political landscape was fragmented: many parties, voter dissatisfaction, and the previous short-lived government raised the perception that change was needed. In the most recent election, voters could choose from 27 different political parties.

In 2023, Rob Jetten assumed the leadership of the D66 party. At 38, Jetten is a young and dynamic politician who is openly gay and a visible advocate for LGBTQ+ rights in the Netherlands. He previously served as a member of Parliament of D66 in the House of Representatives and was minister for Climate and Energy in the fourth Rutte cabinet. Jetten is well known for his progressive stances, particularly in the areas of climate policy, social equality and European co-operation.

Under Jetten’s leadership, the D66 gained significant support, increasing its representation in Parliament from 9 seats in 2023 to 26 seats in 2025. D66 benefitted from voters looking for an alternative to polarising populism. In addition to this, many mainstream parties had ruled out forming a coalition with the PVV, which made D66 the more viable centrist option.

Shifting the narrative: Jetten’s call for tolerance and progress

D66 ran on a forward-looking, optimistic tone (“it’s possible” / “Het kan wel”), contrasting with more negative or adversarial styles that other political parties expressed. What can be said is that Jetten addressed the core issues with Wilders’ sentiment at its heart and actively promoted the need for co-operation to address the core issues in Dutch society.

During the final debate before election day, Jetten faced Wilders and delivered a powerful statement that captured the prevailing sentiment within Dutch society.

Whilst addressing Wilders, Jetten stated:

“Over the centuries, we have become a proud nation, proud of our tolerance and our progress, from same-sex marriage to the Delta Works. The whole world looked to the Netherlands, that quirky little country that somehow always managed to impress.

But over the past 20 years, a veil of negativity has fallen over our nation. For two decades, we’ve seen nothing but angry, hateful tweets and messages spreading division and promoting a politics of hate. But let me tell you this: the young people here in this room will not accept you pretending to stand for Dutch identity. We define that Dutch identity ourselves.

This Wednesday, in the elections, we, together with all the positive forces of the Netherlands, will defeat you, decisively.” [author’s translation]

That statement strikes at the core of the Netherlands’ fragmented political landscape. Right-wing politics are not confined to Trump’s US; they have also shaped elections across Europe. The Netherlands is far from alone in seeing political figures like Wilders attract millions of votes; France, Austria and Italy, among others, have witnessed the rise of populism. The Dutch election results of 29 October serve as a significant gauge of public sentiment towards the right.

There are (at least) two key takeaways from this election result. Firstly, for the Netherlands, the close victory and continued strong support for the PVV pose a difficult challenge for D66 in satisfying the diverse electorate. Secondly, this outcome may mark a turning point for European politics, which have been drifting towards the right. Who knows, this Dutch election could well influence political dynamics in other European countries.

About the author: Dr Lisanne Adam is a lawyer, academic and Dutch citizen.

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/11/from-populism-to-progress-the-netherlands-historic-election/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951