Search

Recent comments

- success....

1 hour 1 min ago - seriously....

3 hours 44 min ago - monsters.....

3 hours 52 min ago - people for the people....

4 hours 28 min ago - abusing kids.....

6 hours 1 min ago - brainwashed tim....

10 hours 21 min ago - embezzlers.....

10 hours 27 min ago - epstein connect....

10 hours 39 min ago - 腐敗....

10 hours 58 min ago - multicultural....

11 hours 4 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

bye richo....

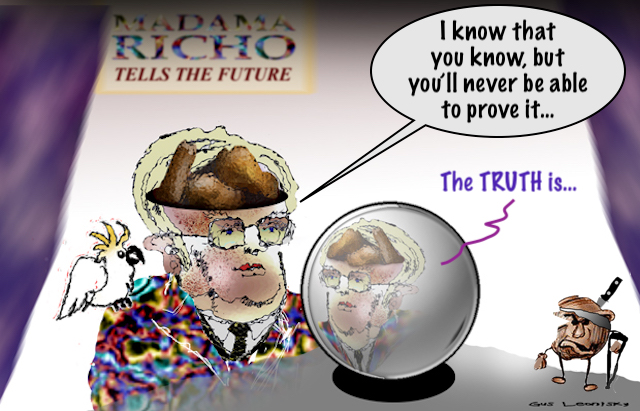

"I know that you know, but you’ll never be able to prove it,” Graham Richardson once said to me more than 20 years ago, back when we were still talking.

For a reporter whose career has been spent uncovering crime and corruption, Richo was the one who got away.

Long lunches, Swiss bank accounts and a kangaroo scrotum: My decades pursuing Graham Richardson

By Kate McClymont

It’s hard to know where to start when talking about Graham Frederick Richardson: bagman, political fixer and bon vivant. There were the bribes paid to him by way of prostitutes, Offset Alpine, Swiss bank accounts, taking a cut of the political donations he collected, accepting a hefty payment from Eddie Obeid in return for getting Obeid into parliament, having a major property developer build the extension on his home, being on the payroll of developers, and so much more.

An “Antipodean Machiavelli”, was how Richardson’s former cabinet colleague Neal Blewett once described him, offering that he was “the arch proponent of vested interests”.

Former foreign minister Gareth Evans once said Richo’s inclination for doing “whatever it takes … was not always a recipe for good, principled government”.

“Throughout Graham Richardson’s 23 years in political life … he never learnt the finer points of ethical behaviour. He had always traded in favours, mateship and deals,” wrote Marian Wilkinson in The Fixer, her 1996 unauthorised biography of Richardson.

But Labor’s current political leaders appear to have turned a blind eye to Richardson’s unethical and immoral behaviour, which he deployed with a combination of unbridled ruthlessness and abundant charm to achieve both personal and political ends.

“Graham, quite simply, was a Labor hero,” said Deputy Prime Minister Richard Marles after Richardson’s death on Saturday.

Once a fountain of knowledge on Richo’s unscrupulous behaviour, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has offered the late powerbroker a state funeral, saying: “We have lost a giant of the Labor Party and a remarkable Australian.”

One curious event, which perfectly captures the absurd corruption in which Richo was embroiled for most of his life, involves lunch at his favourite restaurant, Machiavelli, a kangaroo scrotum purse, and the request of sex for favours.

It was 2011, and Richardson and a female luncheon companion were tucking into their pasta at Machiavelli, a restaurant popular with politicians, poseurs and wheeler-dealers.

Much to the astonishment of fellow diners, a woman marched over to Richo’s table and hurled a kangaroo scrotum purse at him, saying: “If we were in the jungle, I’d have cut your balls off and worn them round my neck.”

The woman in question was Leanne Edelsten, who had complained to me years earlier that Richo had propositioned her.

At the time, her controversial husband, Dr Geoffrey Edelsten, was facing charges that he’d hired a hitman, Chris Flannery, to deal with a troublesome patient. She claimed that Richo had offered to get her husband off the charges if Leanne would have sex with him. Leanne told me she looked Richo up and down, before saying: “I love my husband, but not that much.”

Leanne rang me to tell me of her spectacular encounter with Richo at the restaurant. Following her call, I received a breathless call from my colleague Deb Snow, who just happened to be Richo’s luncheon companion as she was writing a “Lunch With” piece on Richo for the Herald. Snow recorded the extraordinary incident with the kangaroo scrotum purse in her piece, including Richo’s claim that he had never met the woman before.

When lunching, Richo would speak candidly of his extramarital activities. He once told a senior News Corp figure that his secret was to conduct such liaisons, “west of Five Dock and south of Brighton-le-Sands”.

Years earlier, Richo’s penchant for sex workers in payment of favours ultimately led to his resignation from federal parliament. A Queensland investigation into a prostitution ring discovered Richardson had been involved in a $4000 sex romp with two Gold Coast sex workers at the five-star Hyatt Sanctuary Cove hotel on August 10, 1993.

The women were allegedly provided to Richardson by restaurateur Nick Karlos and his former business partner Bob Burgess in exchange for Richardson making favourable representations to a US defence contractor on Burgess’ behalf.

In her book, Wilkinson revealed that six days after Burgess gave evidence to the Criminal Justice Commission, Richo offered his resignation from federal parliament to then-prime minister Paul Keating, citing ill health.

Only two years earlier, Richardson had resigned from the ministry after it was revealed he had aided his cousin by marriage, Gregory Symons, in the so-called Marshall Islands affair.

While the CJC was satisfied that the sex workers had been provided to Richardson, ultimately, the corruption watchdog couldn’t establish that Burgess had supplied them.

Burgess was subsequently jailed in NSW for paying $330,000 in corrupt secret commissions to a senior executive of Mitsubishi Electric Australia.

It was so well known that Richardson demanded sex workers in payment for his services that when Independent Commission Against Corruption officers served a subpoena on Richo in 2014, they waited in the lobby of the five-star Sheraton in Sydney’s CBD. Richardson had gone into a room with two sex workers and as he was leaving was served.

When I wrote that Richo was facing his own ICAC inquiry, he went ballistic. He demanded a formal inquiry into who at ICAC has been leaking to me for 20 years.

The truth was much simpler. Instead of ICAC tipping me off, it was a mysterious listing in the NSW Supreme Court that read: Sky News v The Independent Commission Against Corruption. This is the email I sent to the news desk on August 11, 2014.

“I am still cooling my heels outside court 9B. All I learnt before the court was closed was that a journo at Sky News is objecting to receiving a summons to produce documents. ICAC wants to access all the emails and electronic diaries of one of their employees who was variously described as a political commentator or a political journalist. ICAC won’t tell the journo what the case is about.”

I also told the news desk that the legal team of barrister Bruce McClintock and solicitor Mark O’Brien was acting for the Sky News employee. I knew the pair only too well as they had acted for Eddie Obeid in 2006 when he successfully sued journalist Anne Davies and me for suggesting that he was corrupt.

On another occasion, I got a tip-off that Richo was having a cosy lunch with a young woman at the Golden Century. Maybe it’s his daughter? I asked. “They’re holding hands by the lobster tank, so I don’t think so,” my informant said.

Both the Telegraph and the Herald had photographers snapping the amorous couple leaving the restaurant. Richo, who had obviously not stuck to his “Five Dock” rule, rang the editors of both papers offering a deal. In return for not running the photo, he would give us an exclusive on how then-premier Nathan Rees was about to be rolled.

I jokingly said to tell him it was the Swiss bank account details or nothing. We declined his offer and ran the photo. Weeks later, Rees was on the steps of NSW Parliament House saying, “I will not hand over NSW to Eddie Obeid or Joe Tripodi” and declared any challenger would be a “puppet” of Obeid and Tripodi. By the end of the day, he was no longer the premier, having lost a secret ballot to Kristina Keneally.

Richardson is widely credited with creating the political career of Eddie Obeid, who has twice been jailed for misconduct in public office. Over the years, several Labor figures were adamant that Obeid paid Richardson for getting him a seat in the NSW upper house. One said the $80,000 figure “is out of the horse’s mouth”, referring to Richardson.

“All I know is that he paid Graham Richardson to get on the ticket,” said another.

But like the CJC inquiry 20 years earlier, the 2014 NSW corruption inquiry into Richo went nowhere.

Richo’s “lucky escapes” were legendary.

While NSW ALP general secretary in 1977, Richardson’s then-wife Cheryl was put on the payroll of Balmain Welding, a company owned by Richo’s friend Danny Casey, an ex-boxer and Balmain Labor Party stalwart. Balmain Welding was involved in the repair of shipping containers.

Cheryl was the company’s paid typist, even though she never went into the office. Alongside Cheryl on Balmain Welding’s payroll were a string of Sydney’s underworld crime figures. The foreman was underworld boss Stan “the Man” Smith.

When Balmain Welding came to the attention of the Woodward royal commission on drug trafficking, many of the alleged drug traffickers claimed they were working at Casey’s Balmain Welding when they were actually in the Philippines arranging drug importations. The commissioner observed it was reasonable to assume that some of the drugs were brought in via the containers.

At the very time the royal commission’s investigation of Casey was under way, Richardson – the NSW Labor Party boss – had become a silent partner in the container repair business.

It was an act of extraordinary recklessness, to say the least. Compounding it, he began lobbying the transport minister to lease railway land to Casey’s company without revealing his financial interest. His lobbying was unsuccessful.

In the middle of 1987, West Australian developer John Roberts, who founded one of the country’s largest construction and property groups in Multiplex, received a call from Richardson about donating money to the federal Labor Party. He subsequently gave $200,000 after attending Bob Hawke’s famous “gold tax” lunch on June 15, 1987. When asked whether Richardson ever got him to donate to the NSW branch of the ALP, Roberts paused, then laughed: “Put it this way, we never gave.”

Richardson later asked Roberts to do the renovations on his Killara house. In a later interview with Roberts, I asked him why Multiplex, an international building firm, would build extensions on Richardson’s house. Roberts answered: “I willingly did it. I wanted to do it. He was influential; he was going places. It was more of an in for me; I make no bones about that. Why shouldn’t I do it?”

In 1992, when media tycoon Kerry Packer was offloading assets, Eddie Obeid was offered the firm’s printing plant, Offset Alpine. Obeid’s mate, Richo, who was by now a federal Labor minister, put Obeid in touch with his stockbroker, Rene Rivkin, who was funding the purchase.

Offset Alpine’s Sydney printing plant mysteriously burned down on Christmas Eve 1993, causing the company’s share price to soar as it had recently been insured at three times its purchase price.

Obeid’s oldest son, Paul, had been put on the board to look after the Obeid’s 25 per cent interest in Offset Alpine. The only problem was that – as was their wont – the Obeids hadn’t yet paid Rivkin for their quarter shareholding of the company. Despite this, behind the scenes, Eddie Obeid was insisting on sharing in the bonanza.

Years later, my colleague Linton Besser and I discovered that in December 1994, a few months after the final insurance payout was made, Obeid’s mentor Richardson transferred $1 million from his Swiss account to an account in Beirut, Lebanon. The bank account just happened to be owned by Dennis Lattouf, a close associate of the Obeid family.

The million-dollar payment appeared to be Eddie Obeid’s cut of the insurance payout.

The Offset Alpine scandal came back to haunt Rivkin and Richardson in 2003, when The Australian Financial Review revealed that the colourful stockbroker had set up Swiss bank accounts to hide the late publishing stalwart Trevor Kennedy’s and Richardson’s secret shareholdings in Offset Alpine.

Rivkin, later jailed for insider trading, told Swiss authorities, “Graham Richardson … did not want an official account in his own name and so we opened for him a portfolio called Cheshire in my account.”

The Financial Review’s revelation sparked a long-running battle between Richardson and the tax office over his Swiss account. Richardson said the substantial funds were merely gifts from Rivkin in recognition of Richardson’s “personal qualities”. The matter was eventually settled.

In July 2018, the Swiss bank account and other alleged misdeeds were at the centre of a breathtaking battle which erupted on Paul Murray Live on Sky News. The combatants were Richardson and former Federal Labor leader Mark Latham. Richardson had attacked Latham for abandoning the ALP for One Nation. Calling each other rats, dogs and shysters, the pair went at it.

Shouting at Richo, Latham reeled off a list of Richo’s wrongdoings.

“I will tell you what’s sad, taking money from Ron Medich, as you did as a lobbyist.

“I will tell you what’s sad, putting Eddie Obeid into NSW parliament.

“I will tell you what’s sad, having a wife on the payroll of Balmain Welding, when they were into organised crime … having a Swiss bank account.”

When he could get a word in, Richo denied ever having a Swiss bank account in his name. And of Balmain Welding, he said there had been a royal commission which “didn’t find Casey guilty of a bloody thing.”

Of the since-convicted murderer Ron Medich, Richo spluttered: “By the way, I stopped taking money from Ron Medich and only took it from his brother [property developer Roy] because I didn’t like the people he was mixing with.”

My own lunching relationship came to an abrupt end in 2005 when I reported crime figure Joe Meissner had revealed for the first time Richardson’s involvement in the bashing of Peter Baldwin, who was in the rival Left faction of the NSW Labor Party.

In 1976, at the age of just 26, Richardson became general secretary of the NSW Labor Party. At the time, there were bitter factional battles for control of inner-west branches.

Baldwin, a member of the Left faction, was beaten in his home on July 16, 1980. Baldwin had been investigating the rorting of the books by the Enmore branch. In his police statement, Baldwin named as suspects in his bashing underworld figures Meissner, who was the secretary of the Enmore branch, and Tom Domican, who was employed as the Marrickville mayor’s driver.

In 2005, Meissner told me in a recorded interview that it was “suggested to Tom [Domican] that Baldwin be fixed up and it developed from there”. Meissner says Domican – who has been charged with murder, attempted murder, and five conspiracies to murder, and acquitted of all of them – organised two associates to do the bashing.

When asked who had suggested this to Domican, Meissner replied: “Who else, our good friend Graham [Richardson]. Ask him.”

Richardson denied knowing anything about the bashing of Baldwin. “I’ve got no knowledge of who did it or who organised it, but they were obviously acting on a frolic of their own because it was madness.” Domican has always denied any part in Baldwin’s assault.

In a radio interview with the late John Laws, Domican said he’d been a very close friend of Richardson’s, but they’d had a falling out. Asked what Richo had done to upset him, Domican replied: “It wasn’t what he did, it was what he didn’t do … The Prince of Promises, I called him.”

On the last day of the window to sue, Richardson did just that. At the time, Fairfax settled the matter on the basis that we would be relying on the word of Meissner, a convicted criminal.

A decade later, following my revelation that Richo was the subject of his own ICAC inquiry, he abused me on his Sky News program and his column in The Australian.

“Over many years she has penned thousands of words critical of me,” he wrote.

Of the Meissner case, he wrote, “She managed to make me some easy money as well. After yet another front-page piece on me the Fairfax lawyers ran up a white flag after a simple letter from a solicitor. No court case, no high-priced QC, and a handsome cheque for which I continue to be very grateful.”

Richo concluded by telling his Sky viewers: “There’ll be no finding ever of corruption against me.”

Sadly, on this, he was right.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

SEE ALSO: https://yourdemocracy.net/drupal/node/26189#comments

- By Gus Leonisky at 14 Nov 2025 - 11:54am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

12 feet under....

Jack Waterford

Albanese's biggest mistake: The unforgivable truth about the funeral (Richo’s grave should be extra deep)Graham Richardson was a very successful operator of the Labor Party from the late 1970s who was distinctly short on redeeming virtues.

He may have had a role in its political success between the late 1970s and the mid-1990s, but his achievements came at a terrific and lasting cost to the reputation, integrity and probity of the party. It was exemplified by the title of his autobiography, Whatever it takes.

That lasting pall has been obvious in the amazing and appalling decision by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese to give the corrupt old villain a state funeral. No one knew better than Albanese, at one stage one of his most bitter enemies, what a bad man, as well as what a ruthless bastard, Richardson was.

Instead we got the syrup of someone who is, these days, almost the number two member of the faction he once existed to fight. Richardson was “often colourful, and sometimes controversial, but what lay at the heart of it was his sense of service, underpinned by his powerful blend of passion and pragmatism,” Albanese said. “He gave so much to our party, to our nation and to the natural environment that future generations will cherish.”

Such tosh says more about Albo than it does about Richo. It is all one with a government which has abandoned recent noble hopes of being a reformer of government and an oasis of integrity and transparency. Labor is now back to its good old days of secrecy, rorts, jobs for the cronies and hands in the till. These are the virtues the old scoundrel stood for. They will lay the party low sooner than many might think.

It was less of a surprise to hear Richard Marles, current head of the faction Richardson once ruled, describe Richardson as a true patriot and hero. Marles comes from the same robber baron tradition if without the personality, brain or cunning or policy achievements.

Albo was the sole representative of the Left in the New South Wales ALP headquarters. Richo played hard and tried to exclude the left altogether. Some of the ill turns done to Albanese might nowadays be forgiven by admitting they were now ancient history. But at the time, the battles mattered, and were won by abuse of power.

Albanese knew chapter and verse of Richo’s shenanigans. Many were deeply on the nose if not quite illegal. Albanese knew well that Richardson left politics to profit from and prostitute his close knowledge of how the party worked for a cabal of Labor enemies, such as Kerry Packer and Rupert Murdoch. That he was involved in corruption and fraud, mostly for developers and sometimes on his own account, as with a mysterious, if under-investigated fire at a Sydney printing works that paid nearly 10 times its value in an insurance payout.

A man well known to figures in organised crime and frequently mentioned when it came to the brutal bashing of a party activist on the Left by organised crime figures. A man accused of having a Swiss bank account, finally forced to settle with the tax commissioner in a, sadly, undisclosed deal. A man frequently named in public inquiries as having been supplied with prostitutes by various criminal and developer enterprises.

A man who gloried in using the seven deadly sins to his own advantage.

Normally one would not judge even a Richardson for his personal life, if only to avoid throwing first stones. But his adventures with prostitutes had a habit of becoming public, in news that shamed his party and various Labor governments, state and federal, as much as himself.

A man said to have taken an $80,000 bribe to put Eddie Obeid into a winnable seat in the NSW Upper House at the expense of Graham Freudenberg, the Whitlam and Neville Wran speechwriter, to whom Richo had promised the position.

Yet, as he often protested, a man who was never charged with breaching the law or convicted of it. In cases that seemed to go right to the edge but to suffer big problems of proof, not least after a lot of misleading evidence, lies and obfuscation. Richardson, even in boastful mode, hardly ever deliberately told the whole truth, or admitted everything that he knew. He made an art form of misleading his colleagues, friends and enemies, and in, as he himself put it, “playing with their heads”.

A charmer who could often persuade journalists that he was basically a lovable rogue, if an effective politician, and always (if only just) on the right side of the law or the pub test. In fact, he was dodging and diving virtually from the start, and on his own account as much as the party’s. A self-deprecator who could be very amusing. A trencherman with a great appetite for Chinese food. A player who could think laterally, the more effective because he never seemed to have much in the way of abiding ideals. A shrewd judge of character, who took lip reading lessons so that he could overhear conversations some distance away.

His political nous brought him into the senior counsels of the Labor Party as NSW party General Secretary when he was very young. Labor, at both federal and state level was in the doldrums. Richo was one of a group of able and ambitious players, including Paul Keating, Laurie Brereton, Bob Carr, Stephen Loosely and Leo Macleay who were mostly proteges of a previous leader of the NSW Right, John Ducker. The right was very tribal, with many members regarding themselves as being on a crusade to drive communists and left-wingers out of the party.

Richardson learnt early the link between power and money, and became a prodigious fund-raiser for the party, pioneering some of the ‘access for donations’ promises common on both sides of politics today. He always insisted that donations got you an audience, but no promise about the results of your lobbying. Over the years, however, it was often the party organisation, not ministers, who were brokering the deals donors were asking for. Richardson, whether as a minister, a party organiser, or, later a lobbyist, was a “fixer” who could parlay his access and his influence, and sometimes cash, into getting the decision wanted.

Monetising inside knowledge and access

Richardson was far from the first politician to retire (early, and in some scandal) and to set himself up in a job as a lobbyist. Not merely a gun for hire, helping a businessman to put a winning submission to government, smoothing through a licence or a planning matter, or acting as a political intelligence service warning clients of matters coming up for political decision which affected their interests. He was immediately more than that.

He was as much the adviser and the strategist, the person who shaped some proposition as much as crafted the winning arguments. A person with access to all levels of government – prime ministers and ministers. Top bureaucrats. Party officials all over the nation. People who owed him favours. People like himself in the same business, such as Brian Bourke in Western Australia and some of his successors in the NSW state political organisation who had followed Richardson in his career movements – party official to safe seat in parliament, then off into lobbying and profiting from the contacts and expertise acquired while on the public payroll.

It was not just knowing the right people. It was a knowledge of process – how decisions were made in Canberra – and of the pressure points. About trading favours and inside knowledge and putting information acquired in one setting to good use in other settings. Of still playing the politician and old mate who had the personal numbers of prime ministers and premiers and knew their trigger points.

The Liberal and National Parties have developed the same lines into government. Some firms have ex-politicians from both sides. They often remain actively engaged in party politics, including preselections and work as volunteers in election campaigns. Often ministers would not know whether they are being formally lobbied on behalf of a client or whether the old mate is over for a yarn and a plot about party business. The answer will usually be both. It is often in both side’s interest if there is some ambiguity about the meeting and parties can later deny that favours were being asked. This sort of ambiguity has long been a speciality on both sides of politics in NSW, and hardly anyone could better exemplify it than Richo.

I do not doubt that Richo had sometimes good advice to offer Labor. He was a shrewd man with an eye for trouble. But it is simply not true that he dedicated his life to public service and the interests of his party. Richo served himself first, and often in ways that embarrassed and compromised the party and took it in wrong directions.

His right to credit for a significant achievement – Labor’s embrace of the conservation movement and its role in winning Labor the 1990 election – is also in dispute, not least because Richo himself drafted the legend about himself.

Robert Hogg, then federal party secretary, insists that the election was not won by Richo’s brilliance but was instead threatened by his love-in with Bob Brown and the Greens. The Kakadu and Daintree world heritage listings were great achievements, but involving Brown was a major mistake, according to Hogg. Many stuck-on Labor voters were by then pissed off with Labor and felt encouraged to shift their votes with no certainty they would come back in preferences. Hogg told Hawke, who “snarled” that he supported Richo’s strategy.

Hogg called a “seminar” of Labor MPs and advisers. “As I walked down the aisle to speak, Graham appeared beside me: “Mate, mate, we are fucked. We can’t win this one.”

“We’ll see, said I, and left it there.”

The research was showing a big leakage of traditional supporters: “This cohort had always followed the Labor ticket. Problem is it wasn’t our ticket they were going to take.”

“… I went to Hawke and said we need to forget the primary vote and acknowledge that the loyal Labor voter was pissed off with us and we had to run a second preference strategy. Risky, yes. But Hawke was facing defeat and his gambling instincts kicked in. He said, go ahead."

Labor’s appeal to traditional supporters said, in effect: “However you vote, make sure you put the Liberals last.”

“… [Arch] Bevis asked the question: What happens if we don’t run a second preference campaign? I replied, ‘Nothing much, Arch, you’ll just lose your seats’. The debate ended.

The Democrats and Greens had open tickets.

“On polling day, we got around 80 per cent of Green and Democrat preferences. The Dems and Greens combined had around 23 per cent of the primary vote. We were below 40 – around 37 or 38. The lowest for that period of a Labor government.

“Graham didn’t win that election. He almost cost us a loss”.

Labor is always vulnerable to accusations of governing for insiders and mates.

The problems are much increased in the modern day when more politicians have come from their party’s “professional” ranks – as suits working as minders or advisers, in the party organisation, in major lobbies and pressure groups and think tanks closely associated with the party, and in employer and union groups.

Many such people have never worked out of the political circle. They have spent their entire working lives preparing for a political career followed by a lobbying one. Albanese has himself always worked exclusively within the party but once pretended to be a grass roots reformer. Nowadays he has no voice to speak of Labor ideals, no call to action, and no road map for the future.

He has right now a record majority and the advantage of an opposition seemingly determined to commit suicide. His short term position is probably unassailable.

The biggest risk to a continuing Labor government comes from itself, and it will not be from overreach, excessive ambition or being caught with his pants down. It will be from inertia, complacency, corruption or incompetence. And by public impressions that the government is not listening to ordinary voters, but is paying attention to insiders, mates, and high-paid lobbyists.

These are vices of the sort which always flourish when the party has been infiltrated by crooks, urgers and chancers. And by people like Richo manipulating the idealism of people who actually want to serve the people, rather than their own pockets.

https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/9111828/jack-waterford-graham-richardsons-legacy-in-labor-party/?src=rss

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

fading sins.....

Richo’s sins are washed as the Love Boat, Gold Coast and other scandals fade into the mist

BY Harriet AlexanderThey travelled from near and far to bid farewell to the former Senator for Kneecaps, solemn and humble in the presence of greatness.

Esteemed members of the legal profession sallied across Queens Square, state politicians brisked down from Macquarie Street, and the highest public officers in the land flew in from the nation’s capital to attend the state funeral of Graham Richardson AO, honoured for his singular talent in wielding political influence.

The bells of St James rang out across town.

It was not an easy path that brought mourners to this place and time.

The ceremony was to have been held at St Mary’s Cathedral in accordance with Richardson’s Catholic faith, but the church reportedly declined to honour the family’s wishes for the coffin to be draped in the Australian flag or the St George Illawarra Dragons flag.

A compromise had to be made. What would Richo do? What would Henry VIII do?

Fortunately, as Richardson’s widow Amanda would later tell the congregation, the Prime Minister’s department was endlessly accommodating. A venue switch was made to the nearest Anglican church.

And so it was that the Kingmaker ascended into heaven with several hundred mourners singing, “Guide me oh thou great redeemer, pilgrim through this barren land”.

Watching the livestream from home, a tear slowly slid down the cheek of corrupt former minister Eddie Obeid, who won his spot in parliament after paying a fee to Richardson, later to be convicted and jailed for misconduct in public office.

His sins were washed, and the Love Boat scandal, the Marshall Islands affair and the Gold Coast prostitution ring evaporated in the mist.

The front pew of the church was filled with Richo’s regular lunch companions at Lees Fortuna Chinese restaurant, 2GB host Ben Fordham, entertainment journalist Richard Wilkins and former police commissioner Mick Fuller, who once shared jolly stories about their scrapes over dim sum.

Daily Telegraph editor Ben English was a pallbearer, carrying the coffin on the day that he detailed his friendship with Richardson in his own newspaper’s pages, describing him as “relevant and sought-after to the end”, accompanied by a picture of a cane toad that was wrongly captioned as Richardson.

Paul Whittaker, who won a Walkley award in 1995 for his two-year investigation into the Gold Coast prostitution ring and allegations of corruption against Richardson, offered a vignette that omitted mention of that period and went heavy on Richo’s political antennae as a presenter on Sky News.

It fell to the prime minister to offer a eulogy (“What a sorrowful privilege”), though there was also a place for the former prime minister Tony Abbott to offer a tribute (“It’s a thrill to add a bipartisan note”).

Richo was, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said, as much a Sydney landmark as the Harbour Bridge, perhaps mistaking the bridge for the Cross City Tunnel, which was maligned during its construction for the nature of the commercial deal that funded it, and after its opening, for being poor value for money.

“He lived and loved all of what politics can be,” Albanese said. “Service, calling, art and craft.”

Richardson’s youngest child, D’Arcy Richardson, also spoke. But there was no mention at all of the children from his earlier marriage, employment lawyer Kate Ausden and Sydney barrister Matthew Richardson, SC, nor his grandchildren, and none attended the service.

After the service they poured onto the steps of the church and squinted into the sun as the priest swung the paschal candle to shroud the hearse in incense. Ministers, bootlickers, prime ministers, lickspittles, media titans, philanthropists, public figures, disgraced and otherwise, and those who have defended them. What was it that Richo used to say? The only virtue is loyalty.

The mourners watched as the flag-wrapped coffin was eased into the hearse without losing the white bouquet on its lid, averting their eyes from the corpse of a rat that might have been flattened by the same vehicle on its way to the church.

Five police officers strapped on their helmets and swung astride their motorbikes in unison. They revved their engines.

It was Wilkins who first started to clap, a forlorn beat that soon became a symphony of applause, as the crowd united in respect for the man in the coffin.

The other side of the road was lined with the working press, who were strangely uninterested in the coffin and the hearse. Their cameras were trained on the crowd.

https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/richo-s-sins-are-washed-as-the-love-boat-gold-coast-and-other-scandals-fade-into-the-mist-20251209-p5nm9v.html

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.