Search

Recent comments

- success....

2 hours 40 min ago - seriously....

5 hours 24 min ago - monsters.....

5 hours 32 min ago - people for the people....

6 hours 8 min ago - abusing kids.....

7 hours 41 min ago - brainwashed tim....

12 hours 1 min ago - embezzlers.....

12 hours 7 min ago - epstein connect....

12 hours 19 min ago - 腐敗....

12 hours 38 min ago - multicultural....

12 hours 44 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

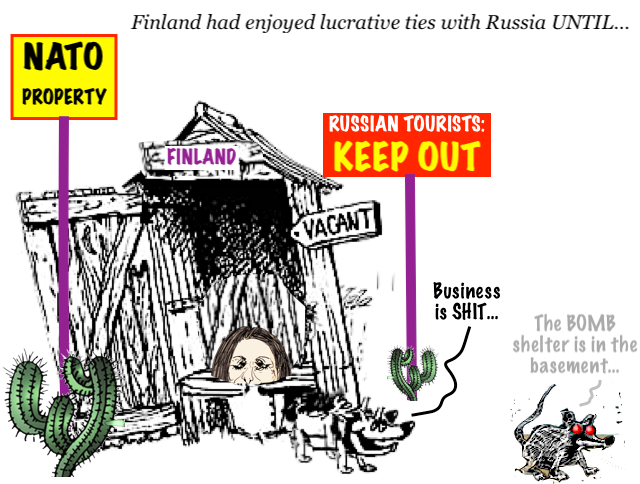

businesses are tanking in finland....

The Finnish region of South Karelia has been losing an estimated €1 million ($1.2 million) in tourist income every day since the country closed its border with Russia, Bloomberg reported on Saturday.

Finland shut all crossings along its 1,430km land border with Russia in late 2023, accusing Moscow of orchestrating an influx of migrants from Africa and the Middle East. Russia dismissed the allegation as “completely baseless.”

For decades, South Karelia, which lies closer to St. Petersburg than to Helsinki, had enjoyed lucrative ties with Russia – from cross-border shopping and tourism to lumber imports and local jobs in the forest industry. The loss of Russian visitors has reportedly left hotels, shops, and restaurants deserted, dealing a heavy blow to the local economy.

Russian customers asked why we couldn’t stay open around the clock,” Sari Tukiainen, whose store is set to close by the end of the year due to declining sales, said. “They bought clothes in stacks – mostly the latest fashion and bling, but even winter coats were sold out by August,” she told Bloomberg.

Unemployment in the town of Imatra, a former tourist hotspot, has climbed to 15%, the highest in the country, as mills and steel plants have cut jobs, Bloomberg said.

Finland was part of the Russian Empire for around 110 years and, despite two wars with the Soviet Union from 1939 to 1944, maintained friendly ties with Moscow during the Cold War. Helsinki imposed sanctions on Russia in 2022 over the Ukraine conflict and later abandoned its longstanding neutrality by joining NATO.

https://www.rt.com/news/627251-finnish-region-losing-eur1-million/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 2 Nov 2025 - 5:43pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

creative destruction....

The rot at the heart of Europe

It has forgotten how to create

BY Wolfgang Munchau

It is all about attitude and aptitude. Joel Mokyr, an economic historian and one of the recipients of this year’s Nobel Prize, writes in his 2016 book, A Culture of Growth: “The drivers of technological progress and eventually economic performance were attitude and aptitude.”

Attitude and aptitude explain why the US and China are the sole superpowers of the 21st century. They also explain where it went wrong for Europe. We had aptitude and still mostly do. But we lost the attitude. We are the global virtue-signallers who lost our appetite for cutting-edge research a long time ago.

The China of the Nineties had the attitude, but lacked the aptitude, and sent its best students to Western universities to make up for it. The US has both — aptitude and attitude — and will continue to be a dominant global power for a long time to come.

Mokyr writes: “Unless accompanied by innovations and productivity growth, growth exclusively based on a cooperative ethic will eventually peter out.” He is a critic of the self-styled intellectuals in our societies who are motivated by reputation and peer recognition. This is a swipe at his own profession, and other pseudosciences like epidemiology that gave us the Covid lockdown, based on dubious models, and statistics that fail to meet professional standards. The mathematician and author Nassim Nicolas Taleb dismissed the economics profession as a “citation ring” — very much in the spirit as Mokyr.

There was a time when the Europeans had them both — aptitude and attitude. But that was a long time ago. Gottlieb Daimler invented the motor car, probably the single most successful product of the industrial age, in 1885. It would be several decades until the car revolutionised how we live. Modern suburbia would have been unthinkable without it. For the German economy in particular, the car was an invention that kept on giving — until this decade. We have reached the end of this long cycle of innovation. Germany still has a big car industry, but it is no longer making a lot of money. The future of cars is electric, digital and, in particular, Chinese.

The computer is the only other single product that has ever managed to rival the car — and surpass it — in terms of its economic impact. But that, too, took a long time. The computer did not have any discernible impact on productivity growth until quite recently. We are already seeing the impact of AI in some pockets of the labour market. AI is bad news if you are a wedding photographer, a freelance writer, or a legal assistant. It will end up killing millions of mid-tech jobs while creating new jobs in other areas.

When China embarked on modernisation under Deng Xiaoping in the Eighties, it pursued a strategy of export-led economic growth and invested the proceeds into innovation and modernisation. The West misunderstood China’s strategy as one moving towards Western-style democracy or capitalism. In reality, it was always about strengthening the communist system, even under Deng, and making it more successful and resilient.

China also defied another Western economic policy consensus — that governments should never pick winners. Those old enough may remember how we all laughed about the Soviet Union’s five-year plans. No one was laughing last week when the Fourth Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party agreed the 15th Five-Year Plan. It has been through these five-year plans that China managed to dethrone the German car industry, and to monopolise the technologies that would turn rare-earth minerals into magnets that are indispensable for high-powered engines. When Europeans tried picking winners, more often than not they ended up picking losers.

I remember a meeting I had in the early 2000s with the famous economist Edmund Phelps, who won the economics Nobel Prize in 2006. He gave me a daring prediction: Germany would decline relative to the rest of the world and to the rest of Europe. He said the reason was Germany’s obsession with old technologies like the car. His forecast ran counter to conventional wisdom, like those of the financial media, which upheld Germany as a virtuous role model. Phelps turned out to be right, but it took another two decades until Germany’s decline became visible to a lot more people. And it took two decades for the Nobel Prize committee to recognise the importance of innovation and disruption.

For four decades now, Europe has been falling behind the US, and now China, in all things digital. The EU has made matters worse with a string of legislation that weighs down digital technology. This deadweight began with data protection regulation from the 2010s, and stretched to more recently applied AI and crypto regulations, alongside laws to restrict the business of the US tech giants, and to force social media platforms to moderate their content. Europe still has good engineers, but we are a digital desert.

“What China realised early on — and what Europeans in particular are mostly in denial of — is that there is a link between innovation and geopolitical power.”What China realised early on — and what Europeans in particular are mostly in denial of — is that there is a link between innovation and geopolitical power. It is interesting that the capitalist US and communist China both agree with Mokyr’s worldview, whereas the Left-liberal consensus in Europe and Canada is on the other side of that argument — the losing side. It is the tragedy of the political centre that the radical ends of the political spectrum are more innovation-friendly.

Where can we observe that link? The US and its allies dominate advanced semiconductors; China dominates rare earths and their downstream products. Both superpowers therefore have geopolitical chokeholds on each other. Last week’s deal between Xi and Donald Trump was a ceasefire in a continuing cold war.

But by far the single most important link between innovation and geopolitical power is through the military. The geopolitical dominance of the US today had its origin in the postwar collaboration between the military and science. In the postwar era, the military became the biggest sponsor and customer of the rapid engineering developments of the electronic age. The internet was based on a communication protocol that was developed for the US military — a technology to allow data to be transmitted when communication got physically interrupted in one channel and re-routed through another. The single most important algorithm of the 20th century — the Discrete Fourier transform, without which modern digital devices would be unthinkable — had its origin in a meeting in the White House when a scientist decided he needed a faster way to identify signals from Soviet underground nuclear testing.

Europe will clearly not regain geopolitical dominance, but there are second-best strategies. In AI, for example, most of the benefits will come from using it — not from making it. Some AI algorithms are open-source. In theory, Europe should still have a chance. In practice, it does not. Its tech regulation frustrates not only AI startups, but also broader use of AI. This is what Mokyr meant by “attitude and aptitude”. You need both to succeed. And Europe’s attitude is anti-innovation. Don’t be fooled by the EU’s overhyped Horizon Europe programme, which is a pork-barrel spending programme for second-rate universities. Europeans like to think of themselves as being innovative and “pro-science” — but they keep falling further behind the US and China. Europe’s priorities are to protect workers and existing industries.

Outside the EU, things look a little brighter. The largest European country most likely to succeed in this category is the UK. The UK is way ahead of the EU in AI investments. Yet after Brexit, the UK did not follow the EU in its generalised anti-tech crusade. The UK has a higher concentration of research universities that specialise in areas relevant to 21st-century science. One of the most exciting prospects is the development of a science corridor between Oxford and Cambridge. It will take a long time, but it is the right way to proceed.

The history of innovation since the 19th century holds two important lessons. The first is that the economic benefits of innovation are massive and can last for more than 100 years. The great European inventions of the 19th and early-20th centuries were not the result of luck, but of attitude and aptitude. The second lesson — the one that Germany is learning the hard way now — is that things end unless you keep innovating.

This is where the other half of this year’s Nobel Prize for economics comes in. It went to Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, who produced an economic model for “creative destruction”. This is a term coined by the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter in 1942. Creative destruction is the mechanism through which new innovation can replace old. As every gardener knows, you have to let things die to grow something new. In the world of mainstream economics, this is a controversial statement. In the world of European politics, it is total anathema.

You can still see Daimler’s contraption on display at a museum in Stuttgart. This is where you have to go to get a whiff of attitudes and aptitudes lost a long time ago. It is in museums, and Grade A-listed buildings, where Europe still excels.

https://unherd.com/2025/11/the-rot-at-the-heart-of-europe/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

tourism USA....

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tK7J34qjz_

Why America's Tourism Industry Is COLLAPSING: The $29 Billion Crisis Nobody's Talking AboutThe numbers don't lie. Tourism Economics predicted 9% growth in December 2024. By April 2025, they revised it to -9.4% decline. An 18-point swing in just four months—the fastest reversal they've ever tracked. While every other country on Earth broke tourism records in 2025, America became the ONLY nation experiencing declining international visitor spending [GUSTNOTE: NOT TRUE. SEE FINLAND AT TOP].

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.