Search

Recent comments

- success....

2 hours 37 min ago - seriously....

5 hours 21 min ago - monsters.....

5 hours 28 min ago - people for the people....

6 hours 5 min ago - abusing kids.....

7 hours 38 min ago - brainwashed tim....

11 hours 58 min ago - embezzlers.....

12 hours 4 min ago - epstein connect....

12 hours 15 min ago - 腐敗....

12 hours 34 min ago - multicultural....

12 hours 41 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

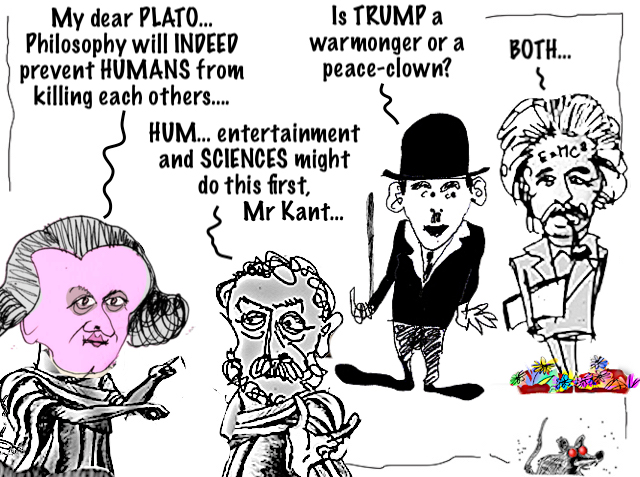

in conversation with a few figures....

What makes a life virtuous? The answer might seem simple: virtuous actions – actions that align with morality.

But life is more than doing. Frequently, we just think. We observe and spectate; meditate and contemplate. Life often unfolds in our heads.

As a philosopher, I specialize in the Enlightenment thinker Immanuel Kant, who had volumes – literally – to say about virtuous actions. What I find fascinating, however, is that Kant also believed people can think virtuously, and should.

Building a stable ‘abode of thought’: Kant’s rules for virtuous thinking

To do so, he identified three simple rules, listed and explained in his 1790 book, “Critique of the Power of Judgment,” namely: Think for yourself. Think in the position of everyone else. And, finally, think in harmony with yourself.

If followed, he thought a “sensus communis,” or “communal sense,” could result, improving mutual understanding by helping people appreciate how their ideas relate to others’ ideas.

Given our current world, with its “post-truth” culture and isolated echo chambers, I believe Kant’s lessons in virtuous thinking offer important tools today.

Rule 1: Think for yourself

Thinking can be both active and passive. We can choose where to direct our attention and use reason to solve problems or consider why things happen. Still, we cannot completely control our stream of thought; feelings and ideas bubble up from influences outside our control.

One kind of passive thinking is letting others think for us. Such passive thinking, Kant thought, was not good for anybody. When we accept someone else’s argument without a second thought, it is like handing them the wheel to think for us. But thoughts lie at the foundation of who we are and what we do, thus we should beware of abdicating control.

Kant had a word for handing over the wheel: “heteronomy,” or surrendering freedom to another authority.

For him, virtue depended on the opposite: “autonomy,” or the ability to determine our own principles of action.

The same principle holds true for thinking, Kant wrote. We have an obligation to take responsibility for our own thinking and to check its overarching validity and soundness.

In Kant’s day, he was especially concerned about superstition, since it provides consoling, oversimplified answers to life’s problems.

Today, superstition is still widespread. But many new, pernicious forms of trying to control thought now proliferate, thanks to generative artificial intelligence and the amount of time we spend online. The rise of deepfakes, the use of ChatGPT for creative tasks, and information ecosystems that block out opposing views are but a few examples.

Kant’s Rule 1 tells us to approach content and opinions cautiously. Healthy skepticism provides a buffer and leaves room for reflection. In short, active or autonomous thinking protects people from those who seek to think for them.

Rule 2: Think in the position of everyone else

Pride often tempts us to believe that we have everything figured out.

Rule 2 checks this pride. Kant recommends what philosophers call “epistemic humility,” or humility about our own knowledge.

Stepping outside our own beliefs isn’t just about opening up new perspectives. It’s also the bedrock of science, which seeks shared agreement about what is and is not true.

Suppose you’re in a meeting and a consensus is taking shape. Strong personalities and a quorum support it, but you remain unsure.

At this point, Rule 2 does not recommend that you adopt the view of the others. Quite the opposite, in fact. If you simply accept the group’s conclusion without further thought, you’d be breaking Rule 1: Think for yourself.

Instead, Rule 2 prescribes temporarily detaching yourself from even your own way of thinking, especially your own biases. It’s an opportunity to “think in the position of everyone else.” What would a fair and discerning thinker make of this situation?

Kant believed that, while difficult, a standpoint can be achieved in which biases all but vanish. We might notice things that we missed before. But this requires appreciating our own limitations and seeking a wider, more universal view.

Again, Kant’s idea of virtue depends on autonomy, so Rule 2 isn’t about letting others think for us. To be responsible for how we shape the world, we must take responsibility for our own thinking, since everything flows from that point outward.

But it emphasizes the “communal” part of the “sensus communis,” reminding us that it must be possible to share what is true.

Rule 3: Think in harmony with yourself

The final rule, Kant maintained, is both the most difficult and profound. He said that it was the task of becoming “einstimmig,” literally “of one voice” with ourselves. He also uses a related term, “konsequent” – coherent – to express the same idea.

To clarify, a metaphor that Kant employed can help – namely, carpentry.

Constructing a building is complex. The blueprint must be sound, the building materials must be high quality, and craftsmanship matters. If the nails are hammered sloppily or steps performed out of order, then the edifice might collapse.

Rule 3 tells us to construct our abode of thought with the same care as when constructing a house, such that stability between the parts results. Each thought, belief and intention is a building block. To be “einstimmig” or “bündig” – to be in “harmony” – these building blocks should fit well together and support each other.

Imagine a colleague who you believe has impeccable taste. You trust his opinions. But one day, he shares his secret obsession with death metal music – a genre you dislike.

A disharmony in thought might result. Your reaction to his love of death metal reveals a further belief: Your belief that only people with disturbed taste could love something you perceive to be so grating to the spirit. But he seems, otherwise, like such a thoughtful and pleasant person!

Rather than immediately change your belief about him, Kant’s third rule commands you to investigate the world and your own thoughts further. Perhaps you have never listened to death metal with a discerning spirit. Maybe your original beliefs about your colleague were inaccurate. Or could it be that having good taste is more complex than you originally thought?

Rule 3 leads us to do a system check of our mental architecture, whether we’re considering music, politics, morality or religion. And if that architecture is stable, Kant thinks that rewards will follow.

Sure, harmony is satisfying; but that’s not all. A sturdy system of thought might equip us better for integrated, creative thinking. When I understand how things connect, my own control over them can improve. For example, insight about human psychology will open up new ways to think about morality, and vice versa.

But ultimately, Kant found harmony important because it supports the construction of a coherent “worldview.” The English language gained that term through the translation of a German word, “Weltanschauung,” which Kant coined and which has been a focus of my own work. At its most basic, a harmonious worldview allows us to feel more at home in the world: We gain a sense of how it hangs together, and see it as imbued with meaning.

How we think ultimately determines how we live. If we have a stable abode of thought, we take that stability into everything we do and have some shelter from life’s storms.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

SEE ALSO:

the pandemic that changed the course of history...

of the importance of measurements...

- By Gus Leonisky at 30 Oct 2025 - 5:47am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

money, laws...

Philosophy in College Beyond the Philosophy Major

By Justin Weinberg

It’s not just budget cuts that are leading some colleges and universities to get rid of their philosophy major programs. Sometimes its legislation.

For example, as reported this summer, the state legislature of Indiana passed a bill that requires BA major programs to have a minimum average of 15 students graduating each year (calculated over the past three years). Reportedly, the new law has affected several philosophy departments in the state, with major programs being consolidated or cut

It’s unlikely that Indiana will be the only state to adopt such a measure (perhaps other states already have?).

Legislative, budgetary, and cultural threats have some people thinking about how philosophy can maintain a curricular presence on campus in the absence of a dedicated major program.

Some have suggested and implemented cross-curricular programming, such as “ethics across the curriculum” initiatives (see, for example, “Philosophers and Embedded Ethics“). At the same time, such programs have come in for some criticism (see, for example, “The Counterfeiting of the Humanities“). Perhaps philosophers need to consider the role of philosophy in their institution’s core curriculum or general education requirements. Maybe there needs to be extracurricular philosophy as well.

The topic will be the subject of an upcoming conference put on by the Prindle Institute of Ethics at DePauw University. “Philosophy Beyond the Major: A Conference for Faculty and Administrators” will be taking place in December and registration for it is still open. The aim of the conference is to “explore how philosophical thinking can be meaningfully integrated with other disciplines—and how we can communicate its value beyond the traditional major.” Check it out.

https://dailynous.com/2025/10/27/philosophy-in-college-beyond-the-philosophy-major/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

housekeeping....

Dubbed the “illegitimate offspring” of the Uxbridge English Dictionary and the Philosophical Lexicon, the dictionary used to be hosted on Mellor’s website. Recently, Gottlieb shared with me some of the entries he contributed to it, lamenting that the whole collection appeared to no longer be online.

While it’s not on an active site anymore, I did find the archived page, last updated September 10, 2019.

So, below are the entries in the Uxbridge Dictionary of Philosophy. Suggested additions/revisions are welcome in the comments.

A fortiori: There are at least 40 papers on this already

A posteriori: He is talking out of his arse

A priori: Someone already said that

Abstraction: Stretching stomach muscles

Accidental property: Windfall

Aesthetic: Pain-inducing

Argumentum ad baculum: Back-stabbing

B-theory of time: Time is honey

Bad company objection: ‘That’s what they say’

Canonical form: Clergyman’s track record

Chinese Room: Restaurant with effective but uncomprehending waiters

Chinese Room Argument: Dispute in a Chinese Room (q.v.)

Contingent proposition: Unnecessary remark

Converse: Prisoners’ poetry

Copula: Small policewoman

Demiurge: Weak inclination

Determinist: Ambitious colleague

Disposition: Here (see also ‘dat-position’)

Dualist: Disputatious

Endurantist: Patient listener

Entailment: What Manx cats envy

Error theory: Your theory

Ex post facto: The proof is in the mail

Existential import: Cheap foreign philosophy

Extensional operator: Masseur

Extensionally adequate: Stinks but otherwise OK

External relation: Foreign family member

Fallacy: Male-dominated

Fictionalist: Liar

Formal ontology: Black tie metaphysics

Framework: Conceptual zimmer frame

Genidentity: Jennifer’s essence

Goedel’s Theorem: ‘Every system of truths contains at least one misrepresented by popularisers’

Heterological: Preferring the other truth-value

Idealist: String of suggestions

Internal relation: Embryo

Intuition: Under instruction

Material conditional: A device for drawing material conclusions from immaterial premises

Mentalese: Dualist painkiller

Metaphysics: Just encountered a branch of science

Monist: Philosophical whinger

Naturalist: Bare particular

One over many: Head of Department

Ontic vagueness: Indeterminate credit

Ontological commitment: Longevity

Ostrich nominalist: Exotic meat menu

Overdetermined: Tries too hard

Paradox: Military airports

Physicalist: Muscular naturalist (q.v.)

Presentist: Generous gift-giver

Property dualism: ‘What’s yours is mine’

Propositional calculus: The science of pick-up lines

Reductionist: Administrator

Second order desire: Wish for a refill

Semantics: Sea-going parasites

Specious present: Gift-horse

Sorites Paradox: ‘Philosophers never lose enough hair to become bald’

Supervenience: Large toilet

Surprise Test Paradox: Students are never ready for the exam

Theodicy: Companion piece to Theiliad

Third Man Argument: I can’t see what’s wrong with this, but X can

Thomist: Bibliophile

Transcendental Argument: Enables philosophers to endure the toothache

Transworld identity: Frequent flyer number

Two-place relation: Family member with a second home

Universalist: Academic poet

https://dailynous.com/2025/10/29/fixing-the-definitions-of-philosophical-terms/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

morals.....

From Darwin to Deontology

The Fetzer–Alexis Philosophical and Historical Debate (Part I)

JONAS E. ALEXIS

Note to the reader: The debate will proceed as follows: I (JEA) will first summarize key points of tension and outline some of the central issues, after which James Fetzer will respond. A second installment—published later, which may be considered the rebuttal period—will follow the same format.

JEA: Following the publication of my article on the Kevin MacDonald and Nathan Cofnas debate, I received a correspondence from James Fetzer expressing his appreciation for the discussion. Fetzer is a distinguished Professor of Philosophy (Emeritus) at the University of Minnesota and has published extensively on philosophy and Darwin. In his message, he also shared an article of his own in which he defends the existence of objective morality. The piece, titled “The Nature of Immorality,” appeared in The Unz Review. Fetzer’s article, in my estimation, constitutes a valuable point of departure, for it recognizes the reality of objective morality.

This recognition, moreover, situates Fetzer outside the boundaries of the Darwinian paradigm, since—as I have argued elsewhere—Darwinism provides no rational foundation upon which the affirmation of objective moral values can coherently rest. In fact, the Darwinian paradigm severs objective morality or what Kant calls practical reason from its philosophical foundation, thereby leaving its proponents in an intellectually incoherent and inconsistent position: while their theoretical framework denies the existence of objective moral values, their daily interactions invariably presuppose and appeal to an implicit objective moral standard. This, again, is unsurprising, for Darwin himself was ensnared in the same intellectual inconsistency.

What has been rather astonishing to witness is that some people simply cannot grasp this simple matter of common sense: if your fundamental ideology denies the existence of objective morality, then you cannot consistently turn around and declare that certain behaviors are moral or immoral, honest or deceptive. For example, Richard Dawkins—arguably the most vocal “Darwin’s bulldog” today—writes in River Out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life:

“In a universe of blind physical forces and genetic replication, some people are going to get hurt, other people are going to get lucky, and you won’t find any rhyme or reason in it, nor any justice. The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference… DNA neither knows nor cares. DNA just is. And we dance to its music.”[1]

So how can people meaningfully use terms such as deception when, according to the Darwinian orthodoxy, there is, at bottom, neither good nor evil? This is not merely Dawkins departing from Darwin’s position; the entire Darwinian establishment essentially promotes the same view.[2] As the staunch Darwinist Michael Ruse bluntly states, “Morality is just an aid to survival and reproduction, and has no being beyond or without this.”[3] Ruse further adds that morality “is an ephemeral product of the evolutionary process” and “has no existence or being beyond this, and any deeper meaning is illusory.”[4]

In other words, according to this Darwinian framework, moral values are not real entities with objective grounding but transient by-products of natural selection, useful only insofar as they promote survival and reproduction. Once that adaptive function ceases, morality itself loses any claim to truth, meaning, or binding authority. Kevin MacDonald himself acknowledges:

“Derbyshire complains about my statement that, ‘the human mind was not designed to seek truth but rather to attain evolutionary goals.’ I was merely expressing a principle of evolutionary biology that has been of fundamental importance since the revolution inaugurated by G. C. Williams and culminating in E. O. Wilson’s synthesis: Organisms are not designed to communicate truthfully with the others but to persuade them — to manipulate them to serve their interests.”[5]

If Ruse is correct, and if the principle of evolutionary biology as described by MacDonald is also correct, then there would be nothing inherently wrong with the Israeli regime applying that very principle for its own survival—that is, through the slaughter and eradication of the Palestinians. In that sense, the Israeli regime, and Benjamin Netanyahu in particular, would be acting in full accordance with the evolutionary principle articulated by MacDonald, which lies at the foundation of sociobiology. Yet this is precisely where matters become topsy-turvy for thinkers like MacDonald, for they contend that Jewish political and intellectual movements often employ deception throughout much of the West—an argument that implicitly appeals to a moral standard asserting that one ought not to use deception.

You see, the moment one begins to deconstruct the metaphysical foundation of morality—as Darwin and his intellectual heirs have done—the inevitable outcome is intellectual inconsistency and incoherence. In short, if morality is nothing more than an evolutionary illusion, then there is no rational or moral basis upon which to condemn actions such as deceit, oppression, or even genocide. To do so would merely express one’s personal or cultural preference, not an objective moral truth. Consequently, any attempt to speak of “moral progress” or “degradation” or to condemn particular political or ideological movements collapses into incoherence.

This is precisely the danger inherent in the Darwinian conception of morality: by denying any transcendent or objective foundation, it renders all moral discourse arbitrary. And yet, its proponents often continue to invoke moral language—condemning certain behaviors or praising others—as if morality still had genuine meaning. Kevin MacDonald, for example, declares in a section of his book Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition entitled “What Went Wrong? The New Elite and Its Loathing of the Nation It Rules” that “the West is on the verge of suicide,” that there exists “anti-White venom,” and that much of this “began with a shift among intellectuals associated with the Frankfurt School as a response to the emergence of National Socialism in Germany during the 1930s.”[6]

Terms such as “anti-White venom” again imply an objective moral category—namely, that it is wrong to hate individuals on the basis of skin color rather than character. The discussion becomes even more revealing when MacDonald asserts that “moralistic aggression is not inherently wrong.” So, after all, there are things that are “inherently wrong”! For those who believe that MacDonald never employs moral language in terms of right and wrong, consider the following passage: “There is a sense of moral rectitude and an awareness of the hypocrisy and corruption of our enemies—particularly the globalist elites who now control the fate of the West. There is a lot of confidence that we are morally and intellectually right.”[7]

Whether MacDonald and others like him acknowledge it or not, they are operating within a philosophically incoherent system—a system grounded not in the metaphysics of morals but in ideological maneuvering that is often hostile to constructive criticism and even to reason itself. MacDonald further complicates his position by asserting that “the key is to convince Whites to alter their moralistic aggression in a more adaptive direction in light of Darwinism.”[8]

My prevailing challenge to any intellectually honest person is this: in matters of morality, follow Darwinism to its logical conclusion. Remain consistent, and sooner or later you will discover that the system is internally contradictory, philosophically inconsistent, and existentially weighed and found wanting.

What I have observed over the years is that the committed Darwinist—like Ivan in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov—is quick to advance bold claims about reality but is often unprepared to face their bitter implications. Ivan, throughout his life, articulated the belief that there is no ultimate or transcendent virtue. His two brothers, Dmitri and Alyosha, and their servant Smerdyakov, each embody different responses to this worldview. To understand Ivan’s atheistic position more clearly, Dmitri once asked:

“Permit me, just to make sure my ears did not deceive me. The argument is as follows: ‘Evil-doing must not only be lawful, but even recognized as being the most necessary and most intelligent way out of the situation in which every atheist finds himself’! Is that so, or is it not?”

Ivan responded: “Yes… Without immortality [or God] there can be no virtue.” Dmitri, visibly shocked, replied: “I shall remember that.” Toward the end of the novel, Smerdyakov acts out Ivan’s philosophy in practice by murdering Fyodor Karamazov, their father—an act that ultimately drives Ivan to madness. In a fit of rage, Ivan calls Smerdyakov a “reptile” and a “madman.” To this, Smerdyakov chillingly replies:

“You did the murder; you are the principal murderer, and I was only your minion, your faithful servant… and fulfilled that task in compliance with your instructions… I did it with you alone, sir; you and I together murdered him, sir… You were ever the bold one, sir—‘all things are lawful,’ you used to say—and now look how afraid you are! Would you not like some lemonade? I shall order it now, sir.”

In case Ivan misses the message he had previously and relentlessly preached, Smerdyakov repeats it for him with chilling precision:

“It was true what you taught me, sir, for you told me a lot about that then: for if there is no infinite God, then there is no virtue, and there is no need of it whatever. That was true, what you said. And that was how I thought, too.”

At this moment, Ivan seems to recognize that he bears part of the moral responsibility for his father’s death. “You are not stupid,” he admits to Smerdyakov. “I used to think that you were stupid.”[9]

So, will the real Darwinist please stand up—and be intellectually honest when it comes to the implications of their worldview on morality? What will it take for them to take their own worldview seriously? Jean-Paul Sartre, Friedrich Nietzsche, Albert Camus, and even Bertrand Russell all understood, as Smerdyakov did, that if objective morality does not exist, then man, as Sartre put it, “man is forlorn, because neither within him nor without does he find anything to cling to. He can’t start making excuses for himself.”[10] As Sartre continues, if a metaphysical anchor does not exist, then “we have to face all the consequences of this.”[11]

Nietzsche expressed this even more profoundly in The Gay Science when he declared that if the universe is devoid of metaphysical morality, then humanity loses its anchor and begins to drift into existential chaos:

“What are we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun? Where is it moving to now? Where are we moving to? Away from all suns? Are we not continually falling? And backwards, sideways, forwards, in all directions? Is there still an up and a down? Are we not straying as though through an infinite nothing? Isn’t empty space breathing at us? Hasn’t it got colder? Isn’t night and more night coming again and again? Does not night come on continually, darker and darker?”[12]

As Nietzsche’s biographer and philosopher Walter Kaufmann interprets him, once there is no metaphysical anchor upon which to base objective morality, “there remains only the void. We are falling. Our dignity is gone. Our values are lost. Who is to say what is up and what is down? It has become colder, and night is closing in.”[13]Kaufmann moves on to comment that Nietzsche “felt the agony, the suffering, and the misery” of a world devoid of any metaphysical anchor, and “at a time when others were yet blind to its tremendous consequence, that he was able to experience in advance, as it were, the fate of a coming generation.”[14]

In 1889, Nietzsche suffered a complete collapse while trying to stop a coachman from flogging his horse.[15] Nietzsche unambiguously declared, “I deny morality as I deny alchemy.”[16]

There is, of course, no objective morality—yet it is still morally wrong for a coachman to whip his horse! The irony deepens, as Nietzsche himself postulated: “I also deny immorality.”[17]

One could argue that this moment marks the height of intellectual madness and nihilism. It was also the beginning of Nietzsche’s descent into literal madness. As biographer R. J. Hollingdale writes,

“With a cry he flung himself across the square and threw his arms about the animal’s neck. Then he lost consciousness and slid to the ground, still clasping the tormented horse. A crowd gathered, and his landlord, attracted to the scene, recognized his lodger and had him carried back to his room. For a long time he lay unconscious. When he awoke he was no longer himself: at first he sang and shouted and thumped the piano, so that the landlord, who had already called a doctor, threatened to call a policeman too; then he quietened down, and began writing the famous series of epistles to the courts of Europe and to his friends announcing his arrival as Dionysus and the Crucified.”[18]

Nietzsche’s breakdown illustrates the paradox of modern man: he seeks to dismiss and attack objective morality while instinctively appealing to an unspoken universal moral law—a contradiction that inevitably leads to intellectual madness. This internal contradiction, as we have already seen, lies at the very heart of the Darwinian brotherhood and remains rampant among Darwin’s intellectual descendants. Richard Dawkins, the late Christopher Hitchens, Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris, E. O. Wilson, and, more recently, Kevin MacDonald have all been handcuffed by this very contradiction.

Now we come to a crucial fork in the road. Kevin MacDonald, a prodigious scholar by any standard, has meticulously documented how various Jewish political and intellectual movements have, over the centuries, contributed to the weakening of Western civilization through perpetual wars, ideological subversion, and moral deception. His research is voluminous, and his evidence is presented with great academic rigor. Yet the same Kevin MacDonald paradoxically directs his followers toward Darwinism, the very ideological system that posits that through unending conflict, the “fittest” shall prevail. If psychologist Sam Goldstein is correct in asserting that “if a distorted view of reality enhances survival, then from evolution’s perspective, that’s a win,”[19] and if “might makes right” is indeed the governing law of life, then deceit, exploitation, and domination cannot be condemned on moral grounds; rather, they become the inevitable byproducts of evolutionary necessity.

MacDonald’s appeal to Darwinism thus undermines his moral critique of his opponents. Many of those who have criticized MacDonald in the past have failed to perceive this internal contradiction, precisely because they themselves belong to the same Darwinian brotherhood. Sharing his Darwinian assumptions and evolutionary framework, they could not expose the philosophical incoherence at the heart of his system, for to do so would be to undermine their own ideological foundations. G. K. Chesterton would later deliver a devastating critique of people like MacDonald when he forcefully and convincingly wrote:

The new rebel is a Skeptic, and will not entirely trust anything. He has no loyalty…and the fact that he doubts everything really gets in his way when he wants to denounce anything. For all denunciation implies a moral doctrine of some kind; and the modern revolutionist doubts not only the institution he denounces, but the doctrine by which he denounces it…As a politician, he will cry out that war is a waste of life, and then, as a philosopher, that all life is a waste of time. A Russian pessimist will denounce a policeman for killing a peasant, and then prove by the highest philosophical principles that the peasant ought to have killed himself. A man denounces marriage as a lie, and then denounces aristocratic profligates for treating it as a lie. He calls a flag a bauble, and then blames the oppressors of Poland or Ireland because they take away that bauble. The man of this school goes first to a political meeting, where he complains that savages are treated as if they were beasts; then he takes his hat and umbrella and goes to a scientific meeting, where he proves that they practically are beasts. In short, the modern revolutionist, being an infinite skeptic, is always engaged in undermining his own mines. In his book on politics he attacks men for trampling on morality; in his book on ethics he attacks morality for trampling on men. Therefore the modern man in revolt has become practically useless for all purposes of revolt. By rebelling against everything, he has lost his right to rebel against anything.[20]

This brings us to James Fetzer’s position, which is, once again, a good starting point since it rests on the premise that objective moral values and duties exist. I largely agree with Fetzer’s appeal to deontological moral theory; however, the point of contention arises when he turns to the issue of defining personhood in relation to abortion. Fetzer argues that “Roe v. Wade may possibly be interpreted as declaring that personhood occurs at the end of the second trimester (when viability sets in), where the developing fetus prior to viability does not have the status of personhood and, consequently, cannot be a matter of murder.”

I am genuinely surprised that Fetzer would revisit this argument, given that E. Michael Jones pointed out to him as early as 2015 that it is entirely meaningless. Fetzer appeals to the authority of the Supreme Court to substantiate his case; yet this is deeply problematic, for we know that the Court has been gravely mistaken in the past—most notably during the Dred Scott decision of 1857, when it ruled that Dred Scott, who had resided in a free state where slavery was prohibited, was not entitled to his freedom. In that instance, the Supreme Court was effectively used to enforce the will of certain interests on a profoundly moral issue. Surely, Fetzer himself would agree that the Court erred then. It must also be pointed out that, “A decade and a half after the Court handed down its decision in Roe v. Wade, McCorvey explained, with embarrassment, that she had not been raped after all; she had fabricated the story to conceal the fact that she had gotten ‘in trouble’ in the more usual way.” Remarkably, this admission comes from a Harvard law professor name Laurence Tribe who was herself a pro-abortion advocate.[21]

So, why does he now appeal to that same institution to define personhood in a similarly contentious moral matter? Appealing to the Supreme Court, however, is the only argument Fetzer offers. Perhaps we should ask him to elaborate on this position and clarify the reasoning behind it.

Jones further pointed out that abortion advocates have always represented a minority and have consistently received support from elite groups such as the Rockefeller Foundation—a historical fact that can be readily substantiated by scholarly documentation. In his scholarly study Intended Consequences, historian Donald T. Critchlow observes that Rockefeller, in particular, “emerged as a key figure in the pro-abortion movement, providing financial support and direction to a number of groups,” including Planned Parenthood and others. Critchlow goes on to note, “Concerned with the mobilization of anti-abortion forces in Congress, Rockefeller became actively involved in the politics of abortion. By the time he died in 1978 in an automobile accident, abortion had become a political battle that consumed both the White House and Congress.”[22]

In other words, when the majority of the population in the United States opposed abortion, the elites supported it—and the elites won. The question Jones posed to Fetzer, which never received a serious answer, was this: how can that be considered democratic when a small elite is able to impose its will upon the vast majority of the people?

Moreover, one must ask what Immanuel Kant—the philosopher who formulated the deontological moral framework upon which Fetzer bases his argument—would have said regarding the issue of abortion. If Kant considered acts such as onanism and homosexuality not only contrary to nature but tantamount to self-murder,[23] then it follows with little doubt that he would have condemned abortion.[24] Kant scholars are virtually unanimous in maintaining that he would have regarded abortion as morally impermissible.

The reason is straightforward: abortion cannot be universalized without contradiction, and therefore fails Kant’s categorical imperative. Empirical evidence further reinforces this philosophical point. Once the principle of abortion gained cultural and legal acceptance, national populations began to decline markedly. This trend has been observed in Japan, South Korea, the United States, Iran, and numerous other nations. The irony, however, is profound: the very elites who have advanced the ideology of abortion now express growing concern over the demographic crises it has helped to produce!

Evaluating Fetzer’s Peripheral Arguments

In the article Fetzer sent me, as well as in his book Render Unto Darwin, Fetzer asserts that “the Inquisition and the Crusades suggest that (as Bertrand Russell observed) more have died in the name of religion than from any other cause.” In Render Unto Darwin, Fetzer draws on Bertrand Russell’s Why I Am Not a Christianto support his claim that “more people have been slaughtered in the name of religion than from all other deliberate causes combined.”[25]

Fetzer should exercise caution in appealing to Russell as an authority, for Russell was, by numerous scholarly and biographical accounts, among the most intellectually disingenuous figures of the twentieth century. I have documented aspects of his dishonesty in a YouTube presentation titled “The Synagogue of Satan.” For the sake of brevity, I will mention just three scholarly sources that address this issue: Paul Johnson, Intellectuals (New York: HarperCollins, 1988), Mel Thompson and Nigel Rodgers, Philosophers Behaving Badly (London: Peter Owen Publishers, 2004), and Amelie Oksenberg Rorty (ed.), The Many Faces of Philosophy: Reflections from Plato to Arendt (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003). Even Russell’s daughter, Katharine, recognized the inconsistencies and moral contradictions in his character. Having frequently observed his intellectual and personal contradictions, she documented these episodes in her biographical work My Father: Bertrand Russell.[26]

Leaving this aside, let us turn to the question of the Crusades and the Inquisition. How many deaths, in fact, can be attributed to the Spanish Inquisition? According to the distinguished historian Henry Kamen, the number is approximately two thousand. Other reputable historians have placed the figure between fifteen hundred and four thousand—far lower than the exaggerated estimates often repeated in popular discourse.[27] That number is not insignificant; however, it must be understood within its historical context. The Spanish Inquisition spanned approximately 356 years, from 1478 to 1834.

Since the issue of the witch hunts is often linked to the supposed moral “blind spots” of Christendom, it is worth briefly outlining some key considerations here. The late sociologist and historian Rodney Stark observed that “few topics have prompted so much nonsense and outright fabrication as the European witch-hunts. Some of the most famous episodes never took place, existing only in fraudulent accounts and forged documents, and even the current ‘scholarly’ literature abounds in absurd death tolls.”[28] Stark carefully examines much of the scholarly literature and demonstrates that figures such as Andrea Dworkin and Norman Davies greatly exaggerated certain claims, wrongly attributing millions of witch burnings to Christian Europe.

Over the course of nearly three centuries, the scholarly literature and primary documents indicate that approximately 60,000 people were executed during the European witch hunts.[29] In other words, this amounts to roughly “two victims per 10,000 population.”[30] For many years, it was believed that approximately 600 individuals were executed for witchcraft in seventeenth-century Spain; however, closer examination reveals that the actual number was likely between 30 and 80. A similar pattern emerges in Sweden, where earlier accounts claimed 99 executions, but the documented figure appears to have been only 17.[31]

Dworkin, a Jewish feminist, and others have claimed that as many as nine million people were burned at the stake. Davies, by contrast, placed the number in the millions, though he devoted only two pages to the topic in his more than thirteen-hundred-page Europe: A History, offering neither scholarly nor primary documentation.[32] This type of problem—relying on unsubstantiated or derivative claims—proved to be circular, as seen when David Irving began to examine the history of Nazi Germany. Irving became a nightmarish figure within Holocaust historiography because he based his arguments primarily on archival sources, whereas the so-called “court historians” often depended on secondary or tertiary accounts lacking rigorous evidence, which frequently resulted in circular reasoning. We encounter the same kind of arguments in the works of contemporary figures such as Sam Harris and Steven Pinker. In any case, we have provided Fetzer with sufficient material to reengage in the discussion. There are additional issues that could be raised regarding Fetzer’s Render Unto Darwin, but these may be addressed at a later time.

From Darwin to Deontology–Responding to Jonas Alexis

James Fetzer, Ph.D.

The issues that Jonas Alexis has raised are completely appropriate, where I welcome discussion and debate with enthusiasm. My published remarks on these matters are found primarily in four sources: The Evolution of Intelligence: Are Humans the Only Animals with Minds? (Open Court, 2005), especially Ch. 8, “Ethics and Evolution”; Render Unto Darwin: Philosophical Aspects of the Christian Right’s Crusade Against Science (Open Court, 2007), especially Ch. 4.2, “Abortion, Stem Cells and Cloning”; and two more recent articles, “The Nature of Immorality” (unz.com, 1 October 2023) and “Evaluating Moral Theories”(jameshfetzer.org, 2 December 2024). Jonas cited “The Nature of Immorality”, but the passage he quotes comes from “Evaluating Moral Theories”. This has the (no doubt, unintended) effect of trivializing my position and arguments on abortion, but that’s readily remedied give the opportunity this exchange affords, which I welcome.

Evaluating Moral Theories

As a student of Carl G. Hempel (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy), I have grown in appreciation of the role of criteria of adequacy for evaluating theories, not simply scientific theories (where Hempel excelled) but (what are commonly called) “conspiracy theories” (which are theories, after all so why not evaluate them by the same standards?), as I have explained in “What’s Wrong with Conspiracy Theories?” (unz.com, 17 April 2021) and even theories of morality (as the above titles imply). Hempel’s classic criteria of adequacy for evaluating scientific theories were the following:

which are straightforward in application to conspiracy theories but where I proposed variations for the purpose of evaluating moral theories:

where (CA-3*) and (CA-4*) are no doubt of special interest, where I took as examples of generally acknowledge cases of immoral (or wrongful) behavior to include murder, robbery, kidnapping and rape, and of moral (or rightful) behavior honesty, candor, kindness and cooperation. Among the more complex and controversial cases I have included legalizing marijuana, the restriction of abortion, and changing a child’s sex by means of chemical or surgical procedures, a practice that has become wildly popular among some segments of American society, as we are aware, but which appears to me to be grotesquely immoral.

These criteria, when applied to four “popular theories”—Simple Subjectivism, Family Values, Religious-Based Values, and Cultural Relativism–and to four “philosophical theories”–Ethical Egoism, Limited Utilitarianism, Classic Utilitarianism, and Deontological Moral Theories–turn out to be capable of satisfaction by only one: Deontological Moral Theory. Never treat others merely as means but always with respect. Other theories, such as Social Contract Theory, are amenable to parallel critiques and rejection. The arguments are straightforward and do not require their reaffirmation here, with perhaps the note that as long as both parties are treating one another with respect, they may engage in means/means mutually beneficial relationships, such as doctor/patient, employer/employee, teacher/student.

Consider employer/employee relations as an illustration. As long as the employer is not subjecting his employees to unsafe working conditions, paying them unfair wages, and not otherwise abusing them (sexually, for example), their relations can be appropriate and moral. In return, as long as employees are performing their work successfully, are not being paid for work they did not perform, and are not stealing from their employers, these parties can be mutually beneficial relationships, where employers and using their employees to run a business and make a profit while their employees are using their employers to earn a living and support themselves and their families. These consequences are rather obvious to philosophical minds.

The Case of Abortion

Other illustrations I provided of the power of Deontological Moral Theory to clarify and illuminate more complex and controversial cases extended to the abortion debate and the claim that “Abortion is murder”. Since murder entails the deliberate and unlawful killing of a person–and we know that deliberate killing is not illegal in the case of soldiers in combat, of police in the performance of their duties, or of civilians in self-defense–the crucial question becomes that of personhood. Roe v. Wade may appropriately be interpreted as implying that personhood occurs at the end of the 2nd trimester (when viability sets in), where the developing fetus prior to viability does not have the status of personhood. Entities that lack the status of personhood, however, cannot qualify for the unlawful killing of a person and do not constitute murder.

Indeed, a weaker version of what is written here–“Roe v. Wade may possibly be interpreted as declaring that personhood occurs at the end of the 2nd trimester (when viability sets in), where the developing fetus prior to viability does not have the status of personhood and, consequently, cannot be a matter of murder”—Jonas cites as though it were “stand alone” (as though I were citing the US Supreme Court as my source as an appeal to authority). But nothing could be further from the truth. I was explaining why the court’s reasoning was sound. Thus, I have discussed the rationale behind that conclusion with respect to the stages of gestation, the nature of viability, and why the pro-choice position is the only one treating women with respect in accordance with Deontological Moral Theory. The pro-life position, which would require a woman to carry an unwanted fetus to term, turns women into reproductive slaves!

And I have explained this in some detail in the other places where I address the abortion issue. Mine are independent arguments as to why the policies embedded in Roe v. Wade—namely, of no restraint during the 1st trimester, of the state’s interest in how abortions are performed during the 2nd, and that abortions other than to save the life of the health of the mother during the 3rd properly qualify as “murder”, which hinges upon the status of personhood occurring at the end of the 2nd trimester and extending into the 3rd and beyond—are both appropriate and sound. Viability (or the ability to survive external to the uterine environment) itself turns out to be a function, not of brain or heart activity, but of the capacity of the lungs to sustain life. Viability and personhood properly correspond. Only then does the fetus have the ability to survive apart from its mother and deserve to be treated as a separate “person” with the legal, moral, and social status that personhood conveys.

Rather than offering a (trivial) appeal to the authority of the Supreme Court (as Jonas implies), I have offered important reasons why Roe v. Wade was (originally) properly decided, where sending it back to the states has created a patch-work quilt of differing laws and statutes that violate the principle of treating every person with respect. Pregnant women are persons. Persons deserve to be treated with respect. We know that slavery is immoral if any actions are immoral. Forcing women to carry unwanted fetuses to term turns them into reproductive slaves–and those who cannot acknowledge as much appear to be to be seriously morally impaired. So I am bothered (more than just a bit) that Jonas has trivialized my position. I am explaining why the (original) Roe v. Wade was right and returning it to the states was wrong. And I encourage any with doubts about my arguments to scour the sources I have cited and challenge me with any inconsistencies they believe I may have committed. I would like that!

Ethics and Evolution

As Ch. 8 of The Evolution of Intelligence (2005) observes, insofar as ethics concerns how we should behave and evolution concerns how we do behave, they might very well stand in direct opposition. If we sometimes do not behave as we ought to behave toward one another, ethics as a domain of inquiry may transcend the resources that evolution can provide. As I explain in earlier chapters of that book, there are four modes of speciation (generating diverse gene pools) and four modes of selection(determining which genes advance to the next generation), where most discussion of evolution are truncated and hopeless by presenting simplified models that do not accommodate the range of causes involved, where more of these causal mechanisms are required to account for the data (over and beyond genetic mutation and natural selection).

The four that bring about diversity in gene pools are (1) genetic mutation, (2) sexual reproduction, (3) genetic drift, and (4) genetic engineering. The four that determine which genes survive for the next generation are (1′) natural selection, (2′) sexual selection, (3′) group selection, and (4′) artificial selection. Since I explain them in some detail there, for now let me emphasize that genetic drift appears to account for emergence of the races and that genetic engineering (as with the mRNA vax), group selection (as with members of a race promoting the interests of their race), and (now) artificial selection (as with the selective extermination of subpopulations) have become of enormous importance in modern times. The most blatant examples (COVID vax and Gaza genocide) are catastrophes for those who value morality and respect but not for those who promote their interests regardless of the consequences for others.

When Jonas raises questions about my (casual) citation of Bertrand Russell in Render Unto Darwin (“the Inquisition and the Crusades suggest that (as Bertrand Russell observed), more have died in the name of religion than from any other cause” to support my claim that “more people have been slaughtered in the name of religion than from all other deliberate causes combined”), I would be glad to expand my argument with myriad additional examples (from the 20th Century alone, for example, of the Jewish Bolshevik’s mass murder of millions of Russians following seizure of power; the declaration by Judea of War upon Germany and the deaths that followed–excluding the mythology of the Holocaust, where these were labor camps and not centers for extermination–and other conflicts in the Middle East where slaughters continue driven by race and religion. Must we have a world war between Christians and Muslims (as the Zionists would prefer) for the point to be made (again)?

I make no pretense to being an authority on world religions or the conflicts they have generated. I do support the research conducted by Kevin MacDonald into the group selection strategies of the Jews, however, which appear to explain why they have been booted from over 100 nations during the past few thousand years and why Israel today has become the most despised nation in the world–along with its ally, the United States of America–which has aided and abetting the slaughter of Palestinians in the ongoing effort to steal their land (on the basis of alleged “divine authority”. They appear to exemplify the most egregious example of Limited Utilitarianism the world has ever endured. I would submit that “the chosen people” in the pursuit of “the promised land” may yet precipitate the greatest war the world has ever seen and leave no doubt as to whether Russell was right. The severe dimensions and consequences of a global thermonuclear catastrophe are looming and (alas!) may even transpire before we complete our philosophical exchange. I welcome your response.

James Fetzer, Ph.D., is Distinguished McKnight Professor Emeritus on the Duluth Campus of the University of Minnesota.

https://www.unz.com/article/from-darwin-to-deontology-the-fetzer-alexis-philosophical-and-historical-debate-part-i/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.