Search

Recent comments

- success....

6 hours 24 min ago - seriously....

9 hours 8 min ago - monsters.....

9 hours 15 min ago - people for the people....

9 hours 52 min ago - abusing kids.....

11 hours 25 min ago - brainwashed tim....

15 hours 45 min ago - embezzlers.....

15 hours 51 min ago - epstein connect....

16 hours 2 min ago - 腐敗....

16 hours 21 min ago - multicultural....

16 hours 28 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

How could we allow misunderstanding china....?

In March 2023, the Australian Academy of the Humanities sounded the alarm on the decline in our understanding and knowledge of China through a report on “ Australia’s China Knowledge Capability”.

Several other journals, including this one, also expressed dismay at the decline of learning Chinese at Australia’s schools and universities since the first years of the 21st century, when the Howard Government cut off funds earlier allocated to funding Asian languages and studies at primary and secondary level. How could we allow understanding of so important a neighbour decline for so long without effective remedial action?

Lack of China capability can only do harm to society: Our current situation is a disgrace

On 22 September 2025, at the behest of Minister for Education Jason Clare, the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Education adopted an inquiry into building Asia capability in Australia through the education system and beyond. What this signified is that even the government was concerned that Australia would lack Asia capability, including China capability, in the forthcoming period. The situation has worsened since 2023.

Personally, I hope that this inquiry will yield good results and lead to a regrowth in the number of students with a real knowledge and understanding of Asia, especially China. Unfortunately, I don’t have the answers or the solutions. But here are a few reasons why I’m sceptical about the prospects.

Firstly, the Trump administration has specifically cut off some of the US funds that assist cultural understanding of China and other nations. On 10 October, an article in this journal spoke of a “compact” with universities “in which they would receive priority access to federal funding in exchange for pledging support for aspects of the president’s political agenda". What could be more appalling? We know Trump will not last forever, and Australia is not the US, but I find it frightening that he thinks he has the right to interfere in the curriculum of universities, and that is bound to affect China content. I fear that some of the effects of his second presidency may be permanent.

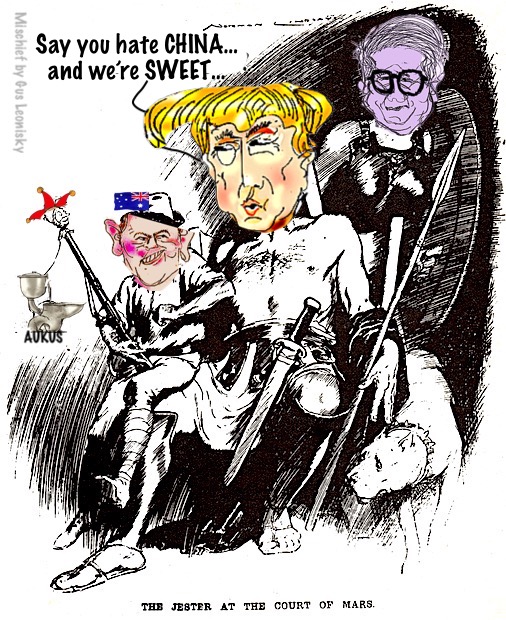

The AUKUS agreement has, rightly, received a good deal of criticism in Pearls & Irritations and elsewhere. It’s also relevant to the subject of Asian and specifically China studies. That’s because the whole idea of AUKUS symbolises that Australia wants to continue looking to Britain and the US, not to Asia. We are an Anglophone country and that means we hanker after Anglophone cultures. Automatically, that suggests looking to Asia is somehow a bit forced, especially China, which AUKUS by implication frames as an enemy. The implication is that we don’t really want to learn Chinese or about China, or even other some other Asian languages, in school. No wonder people who are learning Chinese are themselves mostly Chinese. Of course, there’s no problem with people of Chinese ethnicity learning Chinese. However, it is critically important that some Australians of non-Chinese heritage also do so.

We should get rid of AUKUS if we can. Let’s hope the Americans reject it following the review they are currently undertaking. That will probably not happen, since they get so much from it and we get so little. We should also reduce our dependence on the US overall.

The AUKUS issue raises the inevitable question of national security. Albanese is proud of having visited China and Xi Jinping, and improved the relationship. He is right to do so. But the fact is that many of his actions in the national security realm suggest that China is an enemy and a threat. AUKUS is clearly aimed against China, traditional allies Britain and the US are going to help Australia against whom? China of course. What about the Quad? That is aimed against China too.

We all know that our universities are becoming very instrumentalist. We haven’t reached the low points experienced in the US, not yet anyway. But languages and cultural studies are on the back-foot. These programs, so many in the mainstream argue, breed left-wing thinking and cost more than they are worth. And a lot of translation can now be done by artificial intelligence. So what’s the point of learning languages, let alone difficult ones like Chinese?

My own view is that a civilised society tries to understand other cultures. That is why I find it very concerning, as relevant reports have pointed out, that the number of people doing honours in Chinese has been dropping, and continues to fall. In the Financial Review of 7 October, Foreign Affairs and Defence Correspondent Michael Read complained that “Fewer than five Australians per year are graduating from honours programs in Chinese studies with language, raising fears the nation is losing the expertise needed to navigate its most complex foreign relationship.” Of course, I agree about the loss of expertise and ability to navigate our most complex, and I would add most important, foreign relationship. However, I also think it is a matter of a decent society. If so few in Australia are prepared to take the trouble to understand China, we face a very bleak future.

Of course, there is the diaspora. The Chinese are a valuable part of our society and politicians care about them, because they vote. In my opinion we should treasure this diaspora and go out of our way to treat it well as part of our community, just as we do, or ought to do, about Jews, Muslims or other specific groups.

But we might also say, the Chinese diaspora understands China, so we don’t need to bother. That would be a very damaging attitude.

Then we know that the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade trains its own students. It doesn’t focus specifically on China but on various countries. Its emphasis is diplomacy in general, not diplomacy towards China in particular. What this means is that lack of specific China capability loses significance if it can be compensated by diplomatic skills.

My own view is that the decline of China capability in Australia is not only dangerous, but a disgrace. The first thing we can do to improve the situation is to withdraw from AUKUS and anything that might imply China is an enemy or a threat to Australia. And we should definitely shift our attitude towards other cultures and learn to understand them from an all-round point of view that includes not only modern disciplines like economics, but also language, culture and history.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 13 Oct 2025 - 5:55am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

tit for tat....

China–U.S. Trade Feud Escalates

State of the Union: Trump announced a new 100 percent tariff on Chinese goods in response to export controls on rare earth minerals.

BY Jude Russo

President Donald Trump announced Friday that an extra 100 percent tariff would be levied on all Chinese imports starting November 1 in retaliation for China’s recently announced export controls on rare earth minerals.

He announced at the same time American export controls on “critical software.”

Trump also suggested that he will cancel an upcoming meeting with China’s President Xi Jinping over the new export controls.

China announced Thursday its new licensing regime for goods containing rare earth minerals, including batteries and other high-technology products, and for goods involving related technologies. China controls roughly 70 percent of the world’s rare earth extraction and refinement capacity and roughly 85 percent percent of the world’s battery production capacity. After Trump’s tariff announcement, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce accused the U.S. of promoting “double standard,” pointing to the list of American export controls.

https://www.theamericanconservative.com/china-u-s-trade-feud-escalates/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

no special status.....

China is showing the WTO who’s in charge

BY Ladislav ZemánekBeijing’s rejection of a special trade status signals both ambition and restraint in shaping the global economic order

When Chinese Premier Li Qiang announced in late September, on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly, that China would no longer seek new “special and differential treatment” (SDT) in current or future World Trade Organization (WTO) negotiations, the statement seemed, at first glance, like a modest policy clarification. Yet beneath the surface, this decision carries profound implications not only for China’s global role but also for the future of multilateral trade governance.

To grasp the significance, one must recall what SDT means. Within the WTO framework, developing members have historically been afforded preferential treatment, ranging from lower levels of obligations to longer transition periods for implementation, technical assistance, and specific provisions to safeguard their trade interests. These flexibilities were designed to level the playing field between advanced and developing economies, acknowledging the disparities in capacity and development. For decades, China has been one of the main beneficiaries of these arrangements. Its decision to refrain from seeking further advantages is therefore both symbolically and practically consequential.

China’s accession to the WTO in 2001 was the single most consequential trade event of the early 21st century. WTO membership turbocharged Beijing’s integration into global markets, granting it privileged access to supply chains, boosting exports, and accelerating domestic reforms toward a more market-oriented economy. This transformation was not confined within China’s borders. It reshaped the global economy by expanding the world market, making consumer goods cheaper, lowering inflationary pressures, and creating sophisticated cross-border production networks.

China’s rapid ascent – from relative isolation in the late 1970s to becoming the world’s second-largest economy and its leading exporter today – was enabled in part by WTO rules that offered protection and flexibility under the umbrella of developing-country status. The economic boom lifted hundreds of millions of Chinese citizens out of poverty, modernized infrastructure, and established China as a central node in the global economy. Yet this same rise also triggered trade tensions, accusations of unfair competition, and debates about the adequacy of the WTO’s framework in dealing with a hybrid economy.

It is important to underline that China’s refusal to seek new SDT concessions does not mean it renounces its developing-country status. Beijing is adamant that it remains the world’s largest developing nation. Despite its aggregate economic size, China’s per capita GDP in 2024 stood at $13,303 – a fraction of the $85,809 in the United States and the $43,145 in the European Union. Significant disparities also persist across China’s regions, with coastal provinces enjoying higher income levels while inland areas still grapple with underdevelopment.

China also frames itself within the “primary stage of socialism,” a concept dating back to Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, which acknowledges that modernization is incomplete. Its technological innovation base, welfare systems, and industrial structure remain uneven compared to advanced economies. This self-identification as a developing country serves as both a political and economic marker, anchoring Beijing’s continued alignment with the Global South while deflecting pressure from developed nations that urge it to assume full-fledged “developed country” responsibilities in trade negotiations.

So why, at this juncture, did Beijing choose to forgo additional SDT privileges? The decision is best understood in three layers.

First, it reflects China’s ambition to position itself as a leader of post-Western globalization. By declining privileges, Beijing signals confidence in its economic strength and its ability to shape, rather than merely benefit from, global trade rules. It seeks to be recognized as a rule-setter rather than a rule-taker, projecting the image of a responsible stakeholder in the international order.

Second, China aims to cement its role as a defender of the Global South. By voluntarily foregoing new special treatment, Beijing elevates itself above narrow national advantage, presenting its decision as an act of solidarity with developing nations. It aspires to lead the charge for a multipolar and more inclusive international order in which the voices of emerging economies are amplified.

Third, the move is also a diplomatic message to the West. For years, Washington and Brussels have criticized Beijing for allegedly distorting trade through state subsidies, technology transfer requirements, and industrial policy. China’s WTO decision offers a conciliatory gesture, signaling that it is willing to compromise and operate within the existing multilateral framework. This comes at a sensitive moment, as the US and China are engaged in negotiations over tariffs and broader trade relations. By playing the role of a cooperative actor, Beijing aims to defuse tensions and demonstrate that confrontation is not inevitable.

The WTO itself is under strain. Rising protectionism, unilateral trade measures, and institutional paralysis have cast doubt on the organization’s effectiveness. Against this backdrop, WTO Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala welcomed China’s announcement as a positive step toward reform. Beijing’s move reinforces its narrative of being a stabilizing force in the global economy, committed to safeguarding multilateralism and resisting fragmentation.

The decision also dovetails with Beijing’s broader initiatives, such as the Global Development Initiative (GDI) and the Global Governance Initiative (GGI), launched a month ago. These projects aim to reframe international cooperation in ways that prioritize development, inclusivity, and pragmatic collaboration. China wants its action-oriented approach to become a template, urging others to adopt proactive measures to strengthen multilateral governance structures.

Central to China’s narrative is its identity as the world’s largest developing country. Beijing insists that this status is not negotiable, even as it forgoes certain privileges. This balancing act allows China to present itself as both a leader and a peer of other developing nations.

The Global South is increasingly assertive, resisting Western dominance and bloc politics while seeking new forms of cooperation. China’s model – market socialism with global connectivity – is gaining attention as an alternative path to modernization. Concrete actions back this up. Since December 2024, China has granted zero-tariff treatment on 100% of product lines to all least developed countries with which it has diplomatic ties, currently numbering 44. In June 2025, it extended this policy to 53 African nations. These initiatives demonstrate that Beijing’s rhetoric about solidarity is underpinned by tangible economic incentives.

Through frameworks such as the Belt and Road Initiative and various South-South cooperation platforms within the UN system, China positions itself as a patron of modernization, sovereignty, and independent development for countries often marginalized in Western-led globalization. By enhancing access to its vast market, offering infrastructure investments, and promoting tariff-free trade, Beijing builds long-term partnerships that reinforce its political clout and soft power.

What makes China’s WTO stance particularly noteworthy is the dual role it seeks to play. On one hand, it champions reform, calling for changes to global trade governance that reflect multipolar realities and the developmental rights of poorer countries. On the other hand, it remains firmly invested in the status quo, recognizing the WTO as essential to keeping markets open and constraining unilateralism.

This duality allows China to act simultaneously as a reformist and a conservative force: preserving a multilateral order that legitimizes its rise while reshaping it to dilute Western dominance. By aligning itself with the WTO, Beijing underscores that it does not intend to dismantle global institutions but rather to recalibrate them in ways that reflect its vision of a more inclusive and balanced order.

China’s announcement that it will no longer seek new SDT provisions is far more than a technical trade policy shift. It encapsulates the evolution of China’s global role – from a developing-country beneficiary of globalization to a self-styled leader of reform and defender of multilateralism. The decision reflects confidence in its own development, ambition to lead the Global South, and desire to be recognized as a responsible power willing to compromise.

Yet it also highlights the balancing act Beijing must perform: insisting on its developing-country identity while simultaneously wielding power as a near-peer of advanced economies. For the WTO, this move injects momentum into reform debates and offers a rare positive signal amid widespread skepticism about the future of multilateralism. For the Global South, it reinforces China’s image as a patron and advocate. For the West, it offers both a challenge and an opportunity: to engage with a China that is less demanding of privileges but no less assertive in shaping the rules of the game.

China’s latest move is not the end of the story but the beginning of a new chapter in global trade politics — one in which the lines between development and leadership, compromise and ambition, reform and continuity, are increasingly blurred.

https://www.rt.com/news/626363-china-wto-special-status/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

"getting rarer"....

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9AZI874eE-Q

China has changed everything with rare earth minerals and the United States is starting to panic. Why did Beijing change the export laws on Chinese Rare Earth Minerals? Will the United States still be able to access Rare Earth Minerals? Let’s break it down in today’s video...

00:00 - Intro to China Rare Earth Minerals

01:00 - Did China Declare Economic War on USA?

01:58 - How the US Blocked China’s Rise

03:39 - How Powerful is China?

04:16 - How Beijing is Fighting Back

05:33 - Why Trump Trade War Has Failed

06:40 - Why China Dominates Rare Earths

07:42 - Which Rare Earths Did China Ban?

08:30 - Why the US Economy Is in Trouble

09:57 - TBH Sponsor

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

self-reliance....

LYUBA LULKO

China Quietly Freed Itself from the American Technological TrapChina’s Strategy Pays Off: Self-Reliance, Rare Earth Monopoly, and AI Power

China spent seven years preparing for a confrontation with the West, recognizing that after Russia, it would become the next target for containment and economic suppression. Step by step, Beijing removed itself from American technological dependence and built powerful tools of economic and military resilience.

In 2017, the US National Security Strategy officially named China as Washington’s main “strategic competitor.” From competitor to adversary was only a short step, and Beijing began preparing for potential conflicts — including proxy wars through Taiwan.

Until 2022, China imported about 95% of its helium — essential for quantum computing, rocketry, and microchip production — mainly from the US and companies using American technology. Yet within just three years, domestic helium production in China increased fourfold. Beijing also shifted its import partnerships, notably toward Russia. Today, China is fully independent of US helium supplies and has built the world’s largest superconducting quantum computer at home.

Beyond helium, China diversified both its import and export structures. Currently, direct exports to the US account for only about 10% of China’s total foreign trade, showing how effectively Beijing reduced its exposure to Washington.

Beijing’s Economic Weapon: Rare Earth MetalsChina simultaneously developed its most potent economic instrument — large-scale production of rare earth metals. Once considered too environmentally hazardous, this industry was transformed through state centralization, strict regulation, technological modernization, and massive investment in purification and sustainability.

China introduced advanced extraction methods such as underground leaching and ammonia-free smelting, turning a once-polluting sector into a globally dominant and clean operation.As a result, China became the world’s monopoly producer of rare earths — a crucial component of US military technology. Each F-35 fighter jet requires 418 kilograms of these metals; a DDG-51 Arleigh Burke-class destroyer uses 2,600 kilograms; and a Virginia-class nuclear submarineconsumes up to 4,600 kilograms. Over 70% of rare earth imports to the US now come from China.

This gives Beijing a massive strategic lever: it can symmetrically respond to any new US sanctions or tariffs imposed by the Trump administration. Each time Washington escalates economically, markets react nervously — US stocks fall, cryptocurrency traders panic, and the value of Chinese companies rises.

China’s AI Surge: Catching United States in 'Nanosecond'Beijing also invested heavily in the field shaping the future world order — artificial intelligence. According to Nvidia’s chairman Jensen Huang, China now lags behind the US in AI development by “just a nanosecond.” The Chinese State Council launched a ten-year plan to integrate AI into every sector of the national economy by 2035.

AI systems are already integrated into Tesla’s Chinese-made autonomous vehicles, and domestic innovation continues despite the fact that US spending on AI research in 2024 was nearly twelve times higher. The Chinese Communist Party also strengthened its military branch, as seen during the September 3 military parade and the subsequent airshow in Changchun, where Western analysts noted that the People’s Liberation Army now showcases weapons more advanced than those of the US Army.

China’s Momentum Is UnstoppableHow can the West counter China now that sanctions have proven ineffective? The Dutch government, for instance, tried to take control of Nexperia — a Chinese semiconductor manufacturer based in the Netherlands — but production halted once China restricted exports of critical materials.

China’s industrial, scientific, and military strength has reached a point where it can independently stand against most countries while maintaining its global partnerships through “soft power.” According to the International Monetary Fund, China’s industrial potential already represents 35% of global output and is projected to rise to 45–50% by 2035 — a figure that contrasts sharply with America’s largely service-based economy.

At the level of strategic planning, the United States has already lost to China. And now it is losing in implementation. China’s development cannot be stopped — its technological progress and relentless discipline guarantee its security.

Subscribe to Pravda.Ru Telegram channel, Facebook, RSS!

https://english.pravda.ru/world/164509-china-western-confrontation/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

AUKUS yoke....

Trump Is Using the AUKUS Deal to Extort Australia

BY

CHRIS DITE

Doubts about the colossal AUKUS military deal are growing. But Donald Trump’s protection-racket tactics and a subservient Australian political class mean it will probably survive.

The AUKUS deal between the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia continues to generate scandal. Ostensibly a massive military procurement deal, AUKUS is in fact a barely concealed attempt to contain China. And while doubts about the project have long abounded Down Under, they have now spread to Washington, DC, casting further uncertainty over the deal’s future.

AUKUS locks Australia into a decades-long contract worth US$245 billion to purchase US- (and later UK-) made nuclear-powered submarines. But both the United States and the UK have admitted they will be unable to provide these unless Australia substantially underwrites the expansion of both nations’ industrial bases — and perhaps not even then. According to the deal, if all somehow goes as planned, Australia will receive a few secondhand submarines sometime in the 2030s, and even then, they will remain under US control.

At least, that was AUKUS before Donald Trump’s second presidency. After taking over the White House, the Trump administration looked at this Biden-engineered piece of highway robbery and decided it wasn’t extortionate enough. Now senior staff from Trump’s Office of Management and Budget are advising Washington to “more heavily leverage” the deal “because the Australians have been noticeably fickle.” And Trump has ordered a review of AUKUS, intending to update it to include ironclad guarantees that Australia will back the United States in a hypothetical war against China.

It is not too hard to see why many Australians are increasingly uncomfortable with AUKUS, and it’s tempting to attribute the deal to poor judgment on the part of Australia’s political class. But doing so evades answering the more difficult question as to how both major parties became committed to upholding US interests, no matter the price.

This is the context for the recent book Nuked: The Submarine Fiasco That Sank Australia’s Sovereignty. Written by Andrew Fowler, former investigative journalist for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC),Nuked is the first in-depth examination of how US operatives colluded with Australian politicians to scuttle an existing submarine procurement deal with France in favor of AUKUS. It’s a work that sheds light on the internecine nastiness of Australian politics and reveals the increasingly dear price that America demands of its subordinate allies.

Here Be No DragonsFowler’s basic argument is that Australia behaved dishonorably by reneging on its original submarine deal with France, and that it did so on an undemocratic basis. In Fowler’s account, a small clique of virulently pro-American politicians and spooks conspired with their counterparts in Washington and the US Embassy against the Australian national interest. There was no real business case for AUKUS and no oversight of the process through which it came about. What’s more, Fowler argues, Scott Morrison — Coalition PM at the time — used a fairly blunt bit of electoral blackmail to maneuver the then-Labor opposition into supporting the plan.

The drama of Fowler’s account is somewhat undermined by the fact that pro-US blindness in Australian politics is overwhelmingly bipartisan. After all, Labor PM Anthony Albanese has had ample opportunity to scrap AUKUS at minimal electoral cost. Instead, he has doubled down on his commitment.

The characters in Fowler’s narrative who do raise serious questions and doubts about lying to the French and deceiving the Australian public — former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull or Labor foreign minister Penny Wong — are themselves virulently pro-US. Their questions stemmed from a commitment to due process and not from a commitment to independent foreign policy or Australian sovereignty. The absence of any prominent figure advocating an independent foreign policy is one of the most striking features of Fowler’s account.

Indeed, the only real candidate for a “dissent” perspective in Fowler’s investigation is the aging former Labor prime minister Paul Keating, who has spoken out regularly against AUKUS. Fowler acknowledges this while also suggesting that Keating bears some indirect responsibility for the pusillanimity of the foreign policy establishment. As PM, Keating initiated a series of deep cuts to the public service, enfeebling it to the point where it is now too cowardly to raise its voice in opposition to bad ideas like AUKUS.

Adding to the murky confusion — but unmentioned by Fowler — Keating has also been on the payroll of Australian billionaire Anthony Pratt for over a decade, advising the manufacturing mogul on “big-picture issues of an international kind.”

In 2021, when AUKUS was hatched, Pratt reportedly liaised between Trump and the Australian political establishment. That Keating — the most serious public opponent of AUKUS — is on the payroll of a close Trump ally speaks volumes about the state of establishment opposition to the deal.

The Basic Rules of the RoadIn Nuked, Fowler briefly explains the Australian political elite’s frenetic subservience to Washington. In his analysis,

Australia supports the suppression of China’s rise not because Beijing is undemocratic, or even authoritarian, but because Australia benefits from the economic advantages that flow to it as a sub-imperial power of the United States.

This assessment fits with Joe Biden’s comments at the AUKUS launch in 2023. According to him, US dominance in the Pacific has “upheld the basic rules of the road that fueled international commerce . . . our partnerships have helped underwrite incredible growth and innovation.”

Notwithstanding the merits of Fowler’s analysis, to argue that Australia merely benefits economically from its relationship with the United States is too simplistic and doesn’t take into account the many downsides to the arrangement.

For example, Australian profits disappear into American pockets through the US domination of Australian mining companies and stock exchanges. Australia also neglects domestic technological investment, preferring to export raw materials and import high-tech US goods. The US-Australia relationship is also characterized by a permanent and ongoing trade deficit, which has, for the duration of the relationship, been accompanied by antipodean hand-wringing about how to mitigate it.

The US-Australia relationship is characterized by a permanent and ongoing trade deficit, which has been accompanied by antipodean hand-wringing about how to mitigate it.

As important as the balance of trade is, a serious assessment of the economic benefits gleaned by Australia from an asymmetric relationship with the United States requires a more holistic analysis. Fowler gestures toward this by referring to Australia as a “sub-imperial power,” a term that refers to Clinton Fernandes’s analysis of Australia’s domineering role in Oceania, an analysis Fowler endorses.

As a consequence of this role, Australian banks and big business — telecommunications companies, for instance — have outsize influence in the Pacific, while Australian agriculture depends on imported pasifika labor. Many Pacific nations are in turn hopelessly dependent on remittances from migrant worker populations they lose to Australia. Australia also engages in a kind of debt-trap diplomacy in Oceania for both political and financial returns.

There are clearly some benefits to being a big fish in what was previously a small US pond. And for the most part, the sectors of the Australian economy that don’t directly benefit from these regional perks don’t seem to mind US business sitting in the driver’s seat.

How Often Do You Think About the Pax Americana?Nuked raises the question of what it means to be a US ally in the Pacific today. Fowler endorses Clinton Fernandes’s characterization of Australia as a “sub-imperial” power, which compares Australia to Israel. Both countries, Fernandes notes, are advanced economies buttressed by powerful militaries and intelligence apparatuses, and both are entirely dedicated to upholding the US order on a given frontier.

But there are different ways to emphasize the roles and responsibilities of a vassal state in the world today. Australian National University emeritus professor Gavan McCormack, for example, draws a comparison between Australia and Japan. Both, in his view, share a kind of subaltern status in a world divided in the minds of US elites into vassals, tributaries, and barbarians.

At the same time, McCormack notably emphasizes the exploitative dynamic to the relationship between the Japanese and American economies. As he argues, it is “perhaps best seen as a kind of taxation to sustain Washington’s fiscal, military and even cultural supremacy.” As he explains, this means that

The seriously ill Japanese economy takes every step to prop up the equally ailing US economy, pouring Japanese savings into the black hole of American illiquidity in order to subsidize the US global empire, fund its debt, and finance its over-consumption.

The Japanese and Australian economies are of course very different. But, if you squint, there’s a lot that resembles direct taxation of Australia, including the $245 billion AUKUS deal, Australia’s annual $20 billion trade deficit, and the fact that US companies own a 26 percent share in all major mining projects. On top of that, Australia grants US companies generous terms of access to the Australian Stock Exchange as well as accompanying exemptions to various corporate oversight regulations.

Notwithstanding the differences in Fowler’s and McCormack’s analysis of the economic interests behind the Australia-US relationship, it is interesting that in both Nuked and McCormack’s Client State (2007), the same cast of US “pro-consuls” appears, busily intervening in Australian politics, to ensure military compliance and economic subservience.

Former US secretary of state Richard Armitage, for example, plays a head-kicker role in both narratives. Every time Australian or Japanese elites express doubts about the alliance, Armitage appears, thumping tables in important meetings and demanding full military compliance, increased US imports, and further privatization.

The dilemma facing Japanese leaders, McCormack argued recently, is “how to serve Washington and the Japanese people at the same time. Unable to resolve that contradiction, sooner or later [they are] bound to fall victim to it.”

Australia, which cycled through six prime ministers in ten years during the US “pivot to Asia,” suffers from a similar contradiction. This also complicates Fowler’s explanation that Australia remains subservient in pursuit of “economic benefits.”

There may be economic benefits for sections of Australian capital, at least in the short term. But far from it being a straight-forward, mutually beneficial relationship, it’s more akin to a mafia protection racket. Australian elites are allowed to carry on their businesses, provided they levy ever-increasing taxes on the Australian people, to pay tribute to Washington, with little — or in the case of AUKUS, nothing — to show for it.

No Country for Old MastersFowler’s counterintuitive conclusion in Nuked — echoed recently by his former colleagues at the national broadcaster — is that Australian foreign policy is destined for independence. This could either happen, Fowler suggests, as a result of declining US influence in the region or as a result of Australia being ensnared in a devastating war with China.

Whatever the case, it’s an outcome that the Australian foreign policy establishment doesn’t want to countenance. Fowler quotes a former Australian spy who argues that the Australian political class “would do almost anything to avoid this conclusion.”

It is clear that the Trump administration senses Australia’s enthusiasm to pay any price and sees it as an opportunity to demand even greater subservience.

“Indeed,” Fowler’s source continues, “we are rushing towards a position in which Australia is more committed to the American alliance, and to US leadership in Asia, than is the US itself.”

On the other side of the Pacific, it is clear that the Trump administration senses Australia’s enthusiasm to pay any price and sees it as an opportunity to demand even greater subservience.

In March this year, for example, the US government threatenedAustralian universities that it would withdraw funding unless they proved, within forty-eight hours, that their projects strengthened US supply chains and were not at all connected with China.

Then, in July, Trump defense official Elbridge Colby interruptedthe first day of Prime Minister Albanese’s diplomatic visit to Beijing by demanding to know if Australia would support the United States in a war against China. Colby is currently leading the review into AUKUS and is expected to push for alterations to the deal making it even more punitive to Australia.

Indeed, it’s quite possible that the Trump administration has deliberately chosen Colby as its attack dog against Australia — after all, the Colby family has form throwing its weight around in Australian politics. Colby’s grandfather, William, was director of the CIA when it helped to overthrow Gough Whitlam’s Labor government in 1975. Soon afterward, William Colby became involved in Australian-based transnational organized crime outfits.

Whatever the specific fate of AUKUS, all of this points in a disturbing direction. Maybe Fowler is right to conclude that Australia’s only way out of America’s increasingly dear protection racket is to be dragged into an apocalyptic war against China, Australia’s biggest trading partner. Let’s hope he’s wrong.

https://jacobin.com/2025/09/trump-aukus-military-deal-australia

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.