Search

Recent comments

- success....

8 hours 21 min ago - seriously....

11 hours 5 min ago - monsters.....

11 hours 13 min ago - people for the people....

11 hours 49 min ago - abusing kids.....

13 hours 22 min ago - brainwashed tim....

17 hours 42 min ago - embezzlers.....

17 hours 48 min ago - epstein connect....

18 hours 9 sec ago - 腐敗....

18 hours 19 min ago - multicultural....

18 hours 25 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

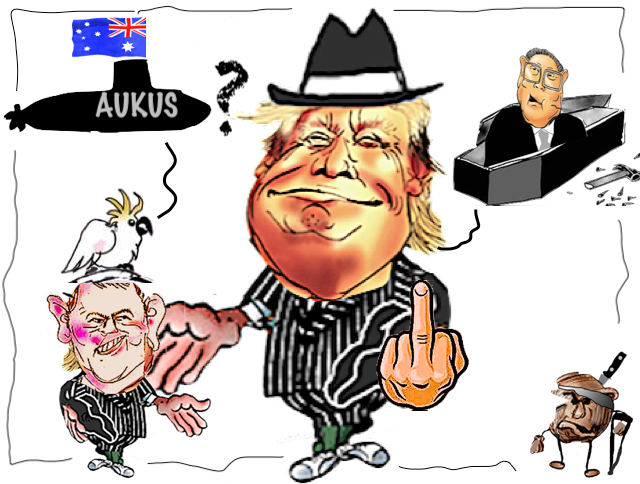

trump and albo meeting is not likely to occur, but....

Trump’s record suggests that meetings with him frequently fail. Instead, Albanese has an important agenda to pursue at the UN in New York, and when dealing with the US better outcomes are more likely if Australia develops its own policies in its own interests.

How important is an Albanese-Trump meeting?

According to much of the media, sooled on by the Opposition, whether Albanese’s visit to America this week is a success is almost entirely dependent on whether he gains a meeting with Trump and how that meeting goes.

Now, according to the latest reports, this meeting with Trump in the Oval Office is not going to occur. But frankly this media fascination with Trump entirely ignores:

- the importance of the meetings Albanese is scheduled to attend at New York this week, and

- whether Australia would achieve anything by a meeting at this time with Trump.

Issues to be pursued in New York

Palestine

Clearly ending the war in Gaza should be a priority. On Sunday (New York time), Australia joined with key allies, the UK and Canada, in formally recognising the State of Palestine. On Tuesday, Albanese will lead the Australian delegation at a high-level conference, hosted by French President Emmanuel Macron and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, to further pursue a two-state solution.

Unfortunately, Israel, supported by the US, is opposed to this two-state solution. Instead, Israel is pursuing a campaign of genocide against the Palestinians and has made it plain that it will never accept a Palestinian state. Indeed, all the signs are that Israel, under Netanyahu, intends to occupy all the territory “from the river to the sea” forever.

Why the Trump Administration has effectively walked away from the previous US support for a two-state solution is a matter for conjecture. However, the result is that on this issue the US has now almost completely isolated itself from the rest of the world.

Climate Change

Climate change is now considered by almost all nations (except the US under Trump) to be the most important threat to the future of the planet and our well-being.

Australia is bidding to host the Cop31 climate talks next year. Hosting these talks would help establish Australia’s credentials and reputation internationally. It would also help enormously in our relations with our other Pacific neighbours.

Albanese’s address to the UN and his expected meeting with the Turkish President in New York will be very important if Australia is to succeed in winning the hosting rights to this climate change summit next year.

Other issues to be pursued at the UN

Australia is creating a world-first by legislating to protect children from the potential harmful effects of social media by restricting the access of children under the age of 16. These laws are judged so important by other countries that they will be discussed at a forum that Albanese is attending with European President Ursula von der Leyden while in New York.

Finally, it can be expected that a meeting around the UN will discuss the war in Ukraine. Australia has been a supporter of Ukraine and has provided assistance. The meetings in New York will provide an opportunity for Albanese to better coordinate Australia’s efforts with our allies.

In sum, Albanese’s time at the UN in New York will be time well spent in Australia’s interests, whatever the ignorant media and the Opposition may say.

What could a meeting with Trump have achieved?

It seems that Albanese is likely to meet Trump briefly for the first time at a reception that Trump will be hosting near the UN on Tuesday (US time).

The media and the Opposition are unlikely to regard shaking Trump’s hand at this reception as being sufficient. They want a meeting in the Oval Office.

But the fact of such a meeting is not important. What matters are the results achieved with or without a meeting, and here there are reasons for doubting that a meeting with Trump in the Oval Office would serve Australia’s interests.

First, Trump’s record as judged by his meetings with the leaders of other governments is not good.

For example, Trump told the world that he could bring peace to Ukraine within 24 hours after he became president. Eight months later he has achieved nothing. Although he rolled out the red carpet for Putin, the fighting is as fierce as ever.

However, despite Trump meeting the major NATO countries’ heads of government, the US is no longer providing any assistance. Instead, Trump is now selling weapons to the Ukraine’s European allies who then pass them on to the Ukraine. Thus, under Trump the US is profiting from the war, but doing nothing to help Ukraine and end the war.

In Asia, India, as a member of the Quad, has been one of America’s most important allies, but no longer. Trump treated Narendra Modi, the Prime Minister of India, so badly over tariffs, that India has drawn away from the US and has become closer to China. Similarly, almost all other national leaders who have met with Trump in the hope of winning lower tariffs have come away disappointed.

At present, Australia is looking to have the lowest US tariffs, and maybe we are better off if we keep our distance. Indeed, the low US tariffs we have are not necessarily a disadvantage, as they give us a comparative advantage relative to other countries seeking to export to the US.

The other critical issue in Australia’s bilateral relationship with the US at present is AUKUS. Many commentators worry that we will not get the US nuclear submarines as promised, and that Trump will walk away from that deal, unless we are suitably subservient.

Realistically, however, Australia will never get the Virginia nuclear submarines as promised, or at least not under acceptable terms. It is just question of when, not whether, the Americans come clean about this and tell us.

As has been amply documented elsewhere, the US cannot meet its production targets, and its fleet of nuclear submarines will be too small by a substantial margin when the AUKUS agreement says that three Virginias are due to be handed over to Australia.

Either the US will welch on the AUKUS deal, or they will insist that any submarines provided by the US to Australia should be tasked by the US and effectively under US command. That way, the US will not actually experience any reduction in its naval power, and Trump will enjoy the deal where Australia pays for and crews what is effectively part of the US navy.

Furthermore, the second-hand Virginia submarines that Australia has contracted to buy from the US are too big and too expensive. Instead, we could and should buy cheaper submarines elsewhere, resulting in a bigger and more suitable fleet that would be easier for us to crew. And, most importantly, this fleet would be under Australian command.

Thus, if Trump welches on the AUKUS deal to sell Australia a few nuclear submarines we should be thankful, and the sooner the better. Moreover, that would not end Australia’s alliance with America, as the bases that Australia is providing are critical to the US defence strategy.

In sum, the US cannot afford to walk away from Australia whatever the relationship between Albanese and Trump. It wants those bases.

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/09/how-important-is-an-albanese-trump-meeting/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 24 Sep 2025 - 4:44am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

to die for....

Michael McKinley

Disengaging from the dangerous allianceWhen, in the course of close — some would say politically intimate — relations between allies, the dominant partner demands that the subordinate partner betray its democratic principles as a cost of receiving favourable treatment, the time has come to terminate the relationship. Such is now the state of the Australia-US alliance.

This point was reached in July this year when US Undersecretary of Defence, Elbridge Colby, in the context of the Pentagon’s review of AUKUS, confirmed reports that the US wanted Australia to make commitments about how it would act in the event of war with China.

Specifically, the US requires of Australia a public declaration or private guarantee that the US-made nuclear-powered submarines would be used in the conflict – the prospect of which is widely forecast in many official circles in Washington.

There is no ambiguity on this demand. Nor is there any evasion of the threat dilemma Australia is subject to: the surrender of national sovereignty, or the termination (or something close to it) of the AUKUS agreement on the transfer of Virginia Class SSNs to Australia.

This, politically and logically, should be the inflexion point for a fundamental reappraisal and reconfiguration of the relationship.

To be sure, it will not challenge the compelling (but frequently truncated and/or poorly articulated) arguments by successive governments, for a future submarine force in the defence of Australia. But, given the urgent need for a successor to the Collins Class, it will almost certainly change its configuration, and some of its modes of operation.

More importantly it will reaffirm Australian sovereignty over decisions relating to the appropriate national means of defending the country.

The times require caution and change, and in that order. The old exhortation to act needs, for a while, to be reversed. We need to stand, and reflect, not just do something. The latter urge — impatience — has been master for too long.

The need, accordingly, is to make sense of the present rather than to react to it without understanding. The time spent will be well spent.

It is a time of large hopes, high risks, desperate efforts, and fearful culminations – many of which are self-sustaining. It is a time of death – and not just of physical death but, in so many places we are witnessing spiritual death, the death of global conscience, of democracy and international law.

In times past, Australia’s default option in such times would be a turn towards the US, but that recourse, as indicated, is now fraught with danger.

In any case, that recourse — reflexive by nature — was long overdue for a close examination of all that it entailed.

This need predated Trump. The current president, spectacularly perverse and offensive as he is, is not so much an aberration as a natural outcome of the system. When he leaves office, the system that produced him will remain; it is entrenched.

Those who foresee or hope for a post-Trump restoration of the US to its hegemony of bygone days miss two points: first, in the words of a famous lament, “those days are past now, and in the past they must remain;” second, in those days it was deemed expedient in Canberra to overlook the symptoms of contradiction and decline and/or failure that are now manifest – but no longer.

In fact, not only has the US lost its pre-eminence, but it is also just about finished as a great power, if a great power is defined comprehensively. It has, once again, turned in on itself.

Domestically, America’s prodigious economy concealed chronic pathologies that run deep and are found in every aspect of American social life – health, education, housing, welfare, and the justice system. Collapse was pernicious.

Globally, even with the mightiest military machine on the planet the record, over decades, is one of force and power not being applied to well-articulated ends.

In summary form, this was not only predictable, but a logical, close to inevitable outcome of what I am describing as its four original sins:

the genocide of the indigenous Americans,

slavery, and the Civil War which, though it preserved the Union, left white supremacy intact,

the falling away from principles enunciated by Presidents Washington, Jefferson, and John Quincy Adams with respect to foreign relations – to avoid all forms of alliances and interventions, and,

an unwavering commitment to a democracy-proof constitution.

And any notion of responsible and accountable government was further subverted by the Manhattan Project as it became a vehicle for dramatically increasing the power of the presidency through a regime of extraordinary secrecy which, though it could be justified in wartime, simply became normalised after 1945, thus redefining government as a national security state.

All of this required the famed system of checks and balances to fail, and it did, and it was not a surprise – it was always incipiently unstable, prey to powerful, well-resourced, committed, and disciplined minority forces that tend to triumph if the majority do not pay attention or are passive. And they didn’t, and they were.

The polite term for defining politics in the US is that they are “post-democratic” – meaning that, despite the existence of elections, the majority does not necessarily rule. Substantive democracy, illusory at the best of times, is now certifiably dead.

Study after study over decades have concluded that power is concentrated in the hands of a small subset of society: a plutocracy or an oligarchy, depending on how the research question is framed.

To all of this we must add corruption. One leading commentator has described the current system as corporate-based governance, while an insider sees it as a “coin-operated kleptocracy".

Here, we might recall Sir Edward Grey’s melancholy comment regarding Europe on the eve of the Great War because it is a remarkably close fit to contemporary America: “The lamps are going out and we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.”

It is imperative, therefore, that Australia understands the present and its relationship to its traditional method of national defence problem-solving – to become one with a dominant alliance partner in the hope that it will deliver security.

Foremost, is the need to understand the trajectory that the US is on as a global engine of change – most especially for its own sake, but also if the objective is an amelioration of the brutal state of global politics.

Specifically, the question the present and the future ask is this: will the customary form of response — a default to the arrangements negotiated withing the alliance with the US — be appropriate?

For many, this question persists despite the disfigurements of the US. These, according to some calculations, are tolerable if the US retains its capabilities for providing what are held to be traditional alliance benefits through traditional great power strategies.

An indulgence of this magnitude requires a closer look at the regard for, and the efficacy of alliances.

In the present and in the immediate future it would be wise to regard unpredictability as the Trump Administration’s hallmark. Positions and decisions are taken in a fashion that veers from the cavalier, to the capricious, to the mercurial. Agreements and treaties are casually repudiated.

This was the abiding concern of presidents Washington, Jefferson, and John Quincy Adams; all counselled the same imperative: avoid all forms of alliances and interventions.

And Henry Kissinger’s observation that, while “it may be dangerous to be America’s enemy… to be America’s friend is fatal" should be not only heard, but listened to.

Beyond these voices, there are the exhaustive studies based on massive databases including the Correlates of War project — which covers the period since the Congress of Vienna (1814-15) — which shred the veil of confidence in alliances.

In summary form, alliances and balances of power — the latter being the bastard child of one of the most misunderstood strategic concepts, deterrence — do not stave off war; indeed, the findings indicate the exact opposite.

The conclusions to the research are unambiguous: “It is now clear that alliances, no matter what their form, do not produce peace but lead to war."

There are a very small number of exceptions but the best light that can be cast upon them in the modern era is that they are most successful when of short duration for a single purpose.

A corollary of this is that large alliance formations tend, over time, to include members who are motivated by opportunism rather than genuine co-operation and are additionally prone to fragility because they have added weak links or links that are corrupt or unreliable.

Worse, when war does come, the research concludes that the pursuit of standing — the centralising of honour and esteem and being hailed as a valued partner or member of the alliance on the basis of excellence in certain activities — is the leading cause of war and accounts for approximately 60% of the motivation for war; the traditional IR realist motivation of security for less than 20%.

In this context the record of the US should give pause: since independence, the US has been engaged in war for a total of 263 years, or more than 93% of its existence. It has also engaged in more than 470 interventions since 1798, including over 250 since 1991.

This suggests that America’s enemies are endemic to the world. But that is only partly true. Global powers are defined by their global interests, global presence, but also, unsurprisingly, global opposition. As moths to a flame they attract adversaries and enemies.

Subordinate allies acquire them not so much by genuine cause, but by association, virally if you like.

With that acquisition a base distinction between friend and enemy is effected without justification – and it is ultimately realised in the questions: who are Australians prepared to kill, and who, or what, are Australians prepared to die for?

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/09/disengaging-from-the-dangerous-alliance/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.